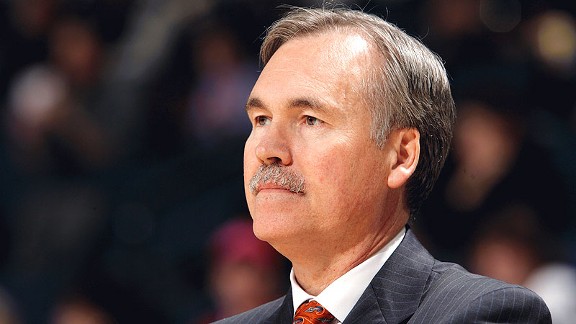

Rocky Widner/NBAE/Getty Images

Rocky Widner/NBAE/Getty ImagesMike D'Antoni: The revolutionary idealist.

Name: Mike D’Antoni

Birthdate: May 8, 1951

Is he an emotional leader or a tactician?

D'Antoni doesn't involve himself in the granular X's and O's of the game so much as he's engaged in a campaign to revolutionize basketball with his tactical principles. Few coaches of this era have influenced today's NBA to the degree D'Antoni has. His contemporaries -- even the most accomplished ones -- deal in battlefield strategy, while D'Antoni is much more of a game theorist. His teams craft their offenses around a few simple sets designed to produce quick results, and the principles guiding those schemes like tempo and spacing are more vital than the minutiae of the plays themselves. Stick to those principles, make smart reads, and you'll be successful.

Many revolutions have anthems, but not D'Antoni's, which features few rah-rah speeches or rallying cries. D'Antoni motivates his players by offering them a system that's fun.

Is he intense or a "go along, get along" type?

Although he's a notorious sideline kvetch, D'Antoni usually carries himself with a loose, casual air, although New York clearly tested his temperament. He projects calm around his team and will rarely rip a guy except behind closed doors, but he is also intensely competitive.

Does he rely on systems, or does he coach ad hoc to his personnel?

Throughout his career, D'Antoni has demonstrated a fundamental devotion to his system, one that preaches attacking immediately, spreading the floor and forcing defenses to react instantly. Players who can't shoot, move the ball, make quick decisions or aren't in condition to run the floor won't see big minutes for D'Antoni, who isn't all that interested in compromising his system to accommodate these shortcomings. For instance, it's nearly impossible to imagine a Mike D'Antoni team playing a power, inside game. It simply isn't in his nature to build an offense around posting up a traditional big. Post-ups become isolations, and isolations breed stasis, which defies the principles of what's popularly known as Seven Seconds or Less.

If D'Antoni wants to post a guy up, he'll do it off pick-and-roll movement, or by running a flex screen way, way off the lane. But you won't see any hulking big men with their paws in the air asking for a simple entry pass from a wing stationed on the perimeter. That simply isn't why Mike D'Antoni got into this business.

Does he share decision-making with star players, or is he The Decider?

His fierce belief in his system and his ego make him The Decider, unless, of course, the star player subscribes unreservedly to the system, as was the case with Steve Nash in Phoenix, but clearly not so with Carmelo Anthony in New York. D'Antoni tried to sell Anthony on the notion that the system makes the game easier than BullyBall does, that it allows a player like Anthony to be more efficient, and that it would tax his body less. Did this pitch make Anthony feel as if his coach didn't believe in his game? On a conceptual level, D'Antoni might not have. These were real artistic differences between Anthony and D'Antoni. Anthony was a conventional basketball player playing for coach who sees shattering convention as a personal mission. Even if you believe D'Antoni was right all along, is it possible he defended the ideal at the expense of problem-solving? The dynamic that materializes between D'Antoni and Kobe Bryant will inform this question a great deal once everyone settles in.

Executive decision-making aside, D'Antoni needs players who can make decisions -- and fast -- because his system requires so many instantaneous reads.

More coaching profiles

Does he prefer the explosive scorer or the lockdown defender?

The explosive scorer, and shooters more than isolation scorers. D'Antoni has traditionally believed his team's best chance of winning occurs when it's putting up 110 points. His allergy to defense is overstated, but he can't accomplish what he wants to as a coach unless there's offensive versatility on the floor. In particular, bigs need to be able to shoot the ball, because that will draw opposing shot-blockers away from the basket, thereby creating space in the middle of the floor for everyone else.

Does he prefer a set rotation, or is he more likely to use his personnel situationally?

D'Antoni prefers a set rotation. He believes in the guys that he believes in, and during the halcyon days in Phoenix, that often meant no more than seven players, each for heavy minutes. His teams don't overpractice and are given a fair amount of rest. So far as game situations, they rarely take precedent over doctrine. Let the other team adjust.

Will he trust young players in big spots, or is he more inclined to use his grizzled veterans?

Despite being an outside-the-box coach, D'Antoni tends to trust the vets because they’re more likely to comprehend a system and make smart decisions on the fly. Yet his most successful teams in Phoenix were populated with a bunch of young guys. The starters on the 62-win 2004-05 team were 30 (Nash), 26 (Shawn Marion), 24 (Quentin Richardson), 23 (Joe Johnson) and 22 (Amar'e Stoudemire). And three of the six 30-minute-a-night players on the 61-win team in 2006-07 were 24 years old, while Marion was still only 28.

Are there any unique strategies that he particularly likes?

A basketball possession is best maximized early in the shot clock. It's during this narrow window when the defense is most vulnerable to attack and the offense controls space on the court. Once the defense gets set, it controls the layer of space around each offensive player, the passing lanes and the basket area. But during those first few seconds, it's squatter's rights in the half-court. If as an offensive player you can stake claim to the corner, it's yours -- and the ball will find you there before a defender can close. If you're a rolling big man, then set a drag screen early while the defense is backpedaling, then dive to the basket. The defense will either collapse, allowing the point guard to find any number of open perimeter shooters, or the ball will be delivered to you with your momentum carrying you toward the basket against a disoriented defense. By pushing the ball, a team can find mismatches, and keeping the middle of the floor open creates all sorts of vectors for drives and cuts. As D'Antoni's players move with purpose at high speed on offense, they must think about the most logical place to run.

In the half court, D'Antoni's offense often generates movement by having the ball handler dribble sharply at a teammate to whom he'll either hand the ball off or use to rub off the pursuing defender to get just enough space to launch a quick-release jumper. Since the defense is stretched thin and constantly lured to the arc, the interior is open for back door cuts (see Marion, Shawn).

These seem like logical precepts, but prior to D'Antoni's success in Phoenix, few NBA staffs adhered to them. D'Antoni is fiercely proud of the system he's popularized, an offense that features interchangeable parts, delights spectators and inspires players. One gets the impression that as much as D'Antoni wants to win a title, he could retire happily knowing he left a profound imprint on the game he loves.

What were his characteristics as a player?

Italian fans nicknamed D’Antoni “Arsene Lupin,” the debonair thief of French crime fiction and cinema who worked deceptively, but as a force of good. As a point guard with Olimpia Milano, D’Antoni was a showman who became the team’s all-time leader in points while leading the team to five Italian League championships.

Which coaches did he play for?

D’Antoni’s coach for 10 of his 12 seasons in Milan was American Dan Peterson, a luminary of the game in Europe who imported the tactical philosophies of Red Auerbach, John Wooden and Ray Meyer to the continent. With D'Antoni running point, Peterson eventually rolled out a run-and-gun offense that provided the inspiration for D'Antoni later in Treviso and the NBA. D'Antoni's coach during the first 20 games of his brief NBA career was none other than Bob Cousy, but D'Antoni played most of his NBA games for Phil Johnson, a Kings fixture during the franchise's nomadic years. D'Antoni also played briefly for Rod Thorn and Joe Mullaney on the last Spirits of St. Louis team.

What is his coaching pedigree?

In Milan, D'Antoni went straight from the court to the first chair. He built an illustrious career as a head coach in the Italian League, where he launched then refined his system. D'Antoni landed in Denver to coach the Nuggets during the strike-shortened 1998-99 team, which ranked sixth in the NBA in pace factor and posted a 14-36 record. In 2002, he joined Frank Johnson's impressive assistant corps in Phoenix that consisted of Tim Grgurich, Marc Iavaroni and Phil Weber. D'Antoni took over the reins in Phoenix midway through the 2003-04 season and immediately pushed the pace. After several seasons of success in Phoenix, D'Antoni became frustrated with new management and ownership and departed for New York. After nearly four seasons of drama with the Knicks between May 2008 and March 2012, D'Antoni resigned. Less than a year later, in November 2012, he assumed head coaching duties for the Lakers.

If basketball didn't exist, what might he be doing?

Subverting the dominant paradigm in the art world.

The spirit of the 1984 Bill James Baseball Abstract was summoned for this project.