Meet the Hero-Makers

By Eric Neel

ESPN.com

It's a blip in the historical record, but for an instant, for a single play, Joe Montana was freaking. His club was down by three, first-and-10 at the Cincinnati 35, with 1:22 left to play in Super Bowl XXIII, and he couldn't breathe. His head was spinning. He motioned to Bill Walsh for a timeout, but the 49ers coach waved him off. So he took the snap, dropped back quickly and heaved the ball out of bounds, hoping he could gather himself before the next play.

Forty-eight seconds and three completions later, as John Taylor clutched a 10-yard pass and a come-from-behind 49ers victory, the moment became a distant memory. Montana had gone 8-for-9 on an 11-play, 92-yard drive. The stuff of legend. But if the drive and the strike to Taylor are the height of Super Bowl glory, then that seized-up feeling in Montana's chest and the wayward ball he sent frantically out of bounds might be the essence of the game.

"The pressure is suffocating down there; there's no air to breathe," says Steve Sabol, president of NFL Films and witness to all 39 Super Bowls. "You make a mistake or come up just short in the Super Bowl, and it feels like the end of the world."

As Janet Jackson and The Fridge can attest, the Super Bowl is special. It commands the biggest audience. The longest pregame hype. The most intense analysis. And that's just the commercials. No other game, no other cultural event of any sort, really, compares. "The Super Bowl is the seventh game of the World Series, the NCAA championship basketball game, the Stanley Cup, the NBA Finals and a heavyweight title bout all rolled into one," says Lynn Swann, a former Pittsburgh Steelers wide receiver and four-time Super Bowl winner. "And actually, it's probably bigger than that." Everything you do, every move you make, is observed and recorded. "There's no hiding in that game," says John Riggins, the former Washington Redskins running back and the MVP of Super Bowl XVII. "Any of us who played in it are defined by it. The Super Bowl is when our legacies go from pencil to ink."

For Riggins, Swann and Montana, the indelible word is Hero. They won the moment, they won the day, and even years later their memories still lift them up.

But there are others -- talented players who wanted it just as badly, prepared just as fiercely, gave every bit as much, and were, in the end, equally defined by the game -- to whom the Super Bowl dictionary was not so kind.

You likely have forgotten these men who came up wanting when they wanted it the most. Those, in some critical moment, who played the frustrated yin to another guy's triumphant yang.

Their memories are more burdensome. Their word is Vanquished.

Here are their stories ...

Intro/Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

E-ticket Archive | ESPN.com | Print | Send to a Friend

Subscribe to ESPN The Magazine

Photo Gallery

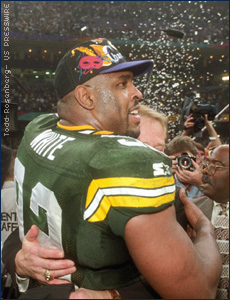

We remember the heroes from the past 39 Super Bowls, but we often forget the men whose dreams were vanquished by their greatness.

We remember the heroes from the past 39 Super Bowls, but we often forget the men whose dreams were vanquished by their greatness.

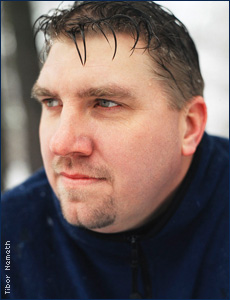

Max Lane is still haunted by his Super Bowl loss nine years ago.

Max Lane is still haunted by his Super Bowl loss nine years ago.

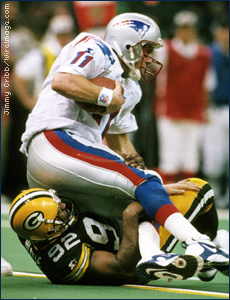

Max Lane, New England Patriots, Super Bowl XXXI

By Eric Neel

ESPN.com

"OK, go ahead"

They were just three little words. Three little words Max Lane wishes he could take back. Three little words that sealed his fate in Super Bowl XXXI in 1997.

Then a 25-year-old third-year right tackle for New England, Lane had been matched up against Green Bay's soon-to-be Hall of Fame defensive end Reggie White throughout the first half. And it was going all right. The Patriots were running a chip, whereby tight end Ben Coates would take a quick shot at White before heading out into his routes, giving Lane an extra half-second to get in position to block the big man. White had a pressure or two, but no tackles and no sacks. "At halftime, I was feeling pretty good about how it was going," Lane remembers. "But of course, we were down 13 then."

After a Brett Favre keeper late in the first half put the Packers up 27-14, the Patriots' tight ends coach, Mike Pope, looking for more offense, came to Lane in the locker room at halftime and asked him about taking the chip off so they could get Coates out in his patterns more quickly.

"It looks like you're doing all right out there," he said.

"OK, go ahead," Lane answered. They were the three words he now regrets.

Maybe he should have thought more about the Pats' having to throw to play catch-up. Maybe he should have resisted his Naval Academy impulse to do whatever was asked of him. Maybe he should have been more realistic about who he was and what Reggie White could do. Maybe he should have ignored the voice in his head telling him he could handle whatever White threw at him. Maybe he should have protested. Maybe he should have shouted, "Are you crazy? Have you lost your mind?!" But he didn't. It wasn't his way. Besides, this was the Super Bowl. This was his moment.

"I was never on Reggie White's level," Lane says. "He was a five-tool player; he was a legend. But you always feel you've got a chance. You always feel you can rise to the challenge."

Down 35-21, on first-and-10 from their own 25 with little more than three minutes to play in the third, the Patriots looked to mount a drive. A screen to Keith Byars on the right gained 5 yards. On second-and-5, quarterback Drew Bledsoe called another pass play. "We were down, and we didn't have a lot of success running the ball at them," says Scott Zolak, New England's backup quarterback and Lane's best friend on the team. "We'd become one-dimensional." White smelled blood. The ball was snapped, and he ran hard to Lane's right shoulder. Lane shuffled and leaned, his weight on his outside foot.

"My technique was terrible. I should have had my weight over my inside foot, but I'm thinking, 'I gotta cut him off, I gotta get in front of him,' " Lane remembers. "And then he pulled his classic hump move. He brings his inside arm up and under my right shoulder. He brings his arm up and then just hits you right across the shoulder and basically just moves you out of the way enough so that he can get a clear path right to the quarterback. You'd see him make the move on film, you know, you'd see him just throw linemen aside and you'd think it was brute strength, but he could have moved me with a tap of his finger. It was the stuff he did before he threw you that made it for him. It was the way he got you off balance and then moved from the outside to the inside. It was what he did to your feet."

White sloughed off Lane like he was shedding an overcoat. In the blink of an eye, Lane went from upright to face-plant: "I'm falling over and I'm thinking, 'Oh s---!'" He pounded the turf in anger while White pounded Bledsoe for an 8-yard loss.

Third-and-13 from the 22. Another pass play. Packers thinking blitz. White's ears pinned back.

"We left Max on an island," Zolak says. "We used to run a thing called 'scat protection,' where we had two backs in a split set. The tailback would free-release into the pattern, and the fullback would pick up the strong inside linebacker on a blitz. But if they blitzed the strong outside linebacker, too, we had to slide the line that way, to the strong side, to try to pick him up. We left Max exposed one-on-one with Reggie on the backside. ... I don't care who you are, even if you're Orlando Pace, you're not going to block Reggie White one-on-one. He's got that power slap move and he does the uppercut up through you, and you just pick your poison -- which one do you want to die with? Because you are going to die."

Lane hunkered down. He had to protect his inside. He couldn't get lured off-balance again. Though his lips never moved, he gave a pep talk to himself: Stay at home. Stay within yourself. Don't look at him. Don't let him dictate. Your game. Your turn. Inside, inside, inside.

At the snap, White jumped back to the outside. Only this time there was no hump. No switchback. "He was in my head then," Lane says, half laughing and half kicking himself. "I played for the inside so much that he went around me. I basically gave him the short corner, the short path to the quarterback."

Down went Bledsoe. Again. Two plays, two consecutive sacks, two times Lane's friends and family back in Norborne, Mo., cringed at the mention of their favorite son's name on television. (There was also a third White-over-Lane sack late in the fourth quarter, but by then the outcome was no longer in doubt.) The whole thing took about a minute; Lane had gone from anonymous to ignominious, from holding his own to holding the bag, in nothing flat.

"I remember Reggie said he felt the adrenaline pulsing through him," says White's widow, Sara. "He said he felt like that game and those sacks were his destiny. He was where he thought he should be. He was completely in his element."

Lane, meanwhile, was a character in a Southwest Airlines commercial: He wanted to get away; he wanted to disappear. The punting team came on the field, and Lane trudged off it, head down, stumbling his way through a line of teammates and toward a bench like one of George Romero's zombies. "I didn't want to make eye contact with people," he says. "I just wanted to be by myself for a while."

There's nothing to be said in a moment like that. "I told him, 'Don't worry about it,' " Zolak says. "But he couldn't hear that then." There was no wriggling or rationalizing. He had to sit with it, experience the full weight of it, and bear it as best he could. This was the moment Montana feared, the feeling he never had to feel. We canonize those who succeed in the big game, but success, no matter how great the pressure, is easy by comparison. Failure is a mean bugger shooting straight for your heart.

Lane was confronted not only with White, or with the hundreds of cameras in the Superdome that day, or with the millions of people watching around the world, but with something even more painful -- his own limitations and the written-down-in-ink evidence that he didn't have enough when it mattered most. "I think to him, those plays were his whole career," says Lane's father, Ezell. "He really struggled with it."

Lane didn't take the team bus back to the hotel after the Patriots' loss. He showered and changed quickly and walked out of the stadium. No interviews. No conversations. "I didn't want anything to do with anybody," he says. "Like Forrest Gump running cross-country, I just wanted to get away." The sacks didn't cost the Patriots the game. As Zolak points out, they lost matchups "all over the field that day." Still, the sense of letting his teammates down lingered with Lane. "We were such a tight team that year," he says. "I hated not being able to make those plays for those guys."

It has been difficult to work through that feeling. "I'll tell you what," he says, "it's tougher than what people think to get over something like that." Patriots coach Bill Parcells (who was heading out the door for the job with the Jets) told Lane to take it as a challenge and be ready the next time he faced White, an opportunity that never came. Other guys on the squad told him to keep his head up. Fans in the streets of Boston would tell him he'd done a good job. But as time passed, Lane says there wasn't much opportunity, or inclination on his part, to talk about what happened. "It's been more internal than anything," he says. "I guess it's hard. But guys are guys. We don't talk about these kinds of things much."

Ezell had often teased Max to get him out of a funk, a father's way of putting things in perspective for his son. Since he had gone away to the Naval Academy, they had spoken by phone several times a week, and his dad would talk him through a post-mortem after every game. In the days leading up to the Super Bowl, Ezell poked at Max to cut the tension. "You take it easy on Reggie White," he said. "Don't you hurt him now." They'd both laugh. "I quit saying that after the game," Ezell says now, his voice falling like a leaf. "We hurt for him. We knew he was hurting, and there wasn't anything we could do to take it away."

Lane played three-and-a-half more seasons with the Patriots, reaching the playoffs twice more, but he never played in another Super Bowl. In 2000, he broke his leg near the knee in a game against Cleveland in the sixth week and was unable to recover. He was picked up, but later cut, by the Houston Texans and retired in 2002 after an eight-year, 100-game career. Over the years, he has replayed the confrontations with White in his head. "I always think in terms of what I could have done differently," he says. He avoided video clips from the game like the plague, though. He'd excuse himself to the bathroom or the kitchen if the game came on ESPN Classic. He stayed away from replays in the days after White died of pulmonary failure in December 2004. "It was like I felt if I just didn't watch it, maybe it didn't happen," Lane says.

Something his father said finally spurred him to watch the clip. "Look at it this way," Ezell joked one day. "That was Reggie White, that was the Super Bowl -- you're in the Hall of Fame!" In fall 2000, the Patriots were playing the 49ers in the Hall of Fame Game in Canton, Ohio. Lane visited the hall the night before the game. He stood before a wall dedicated to Super Bowl highlight reels in one of the display rooms, shifting from foot to foot, sneaking glances over each shoulder. "And finally I thought, 'All right, I'm gonna do it!' " he says. He selected Super Bowl XXXI, hit "play," and the reel began to roll. As game time elapsed, he thought about walking away, but he held his ground. Here came Favre's sneak, then Curtis Martin's touchdown run up the gut in the third quarter, then Desmond Howard's kickoff return for a touchdown. The sacks were next. He dug in, got his balance ... and the reel stopped! Howard's return was the end of the highlights. He was spared by the Hall. "I couldn't believe it," he says. "But I'll tell you what, I didn't push the button a second time!"

That was more than five years ago, and until his cooperation with this story (see accompanying video), Lane still hadn't watched the sacks. When he finally did, for the first time in nine years, the impulse to look away still raged: "It's like 'Oh! I don't want to watch that!' It's like watching somebody get, like, a bad knee injury. Reggie gives me that classic cut move, and I'm like, 'Oh! That hurt!' " But it's not seeing the plays that stings the most, it's the way they work, like some wicked Wonderlandian rabbit hole, to send him tumbling back to the emotions he felt on Super Bowl Sunday, it's the way the footage makes the disappointment and frustration real and present all over again:

"The feeling and the memory of it are worse than watching it. You know watching it, it's just on a tape, and it's over, but it's not over in my head. I've got it up in my head forever."

Sara White worries when she hears that kind of thing. "Does he see that it was a game, that he and Reggie were doing their jobs?" she asks. "I understand that the guys take it very personally and it's not just a game to them, but at the same time, it's not life, right?"

For all his lingering angst, Lane sees that. Regular conversations with Ezell (about the game, about the weather, about nothing at all) and time to reflect have allowed him to see, as his dad sees, the accomplishment woven into the disappointment. "It was a hard day, but it was also a special day," Ezell says. "We were just so thankful that he had done what he had. We were awfully pleased and proud to see him have the honor of playing in a Super Bowl."

Lane knows it's crazy that a kid from Norborne, Mo., could make The Show. He has come to the realization that a few bad plays don't have to erase the other 60-odd plays that went well that day, or the years of hard work he put in leading up to them, either. He understands that once upon a time, as a sixth-round draft pick so afraid of being cut he scurried and hid from Parcells in the halls of the Patriots training camp offices, he lived and thought only in terms of the next day, next game, next season. He gets it ... now. He's not happy about those plays, but he does experience his ride as the magical mystery tour it was.

In the end, for Lane, it's not, as Sara White says, that it's "just a game," it's that it's the game. It's that he played in it, and played hard. And even more than that, it's that he has managed over the years (in ambivalent fits and starts, sure) to make a kind of peace with what went wrong. That peace began with isolation and avoidance, but lately it's blossoming into something that would warm Sara White's heart.

Turns out when Lane isn't dredging up the past for me, and squirming through videotape rehearsals of his most disappointing professional moment, when he isn't rooting around in the bad feelings, he's throwing himself, banged-up knee and all, right back into the game.

He's running classes and clinics for high school-age offensive linemen in and around New England and giving talks about his experiences to young players and their families. "It's pretty small starting out," he says. "But I think it could be something special."

Indeed. You can just see it, right? There'll be classes in the morning on keeping your weight over your inside foot, and sessions in the afternoon on keeping things in perspective.

Intro/Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

E-ticket Archive | ESPN.com | Print | Send to a Friend

Subscribe to ESPN The Magazine

Photo Gallery

It took nine years for Max Lane to finally bring himself to sit down and watch the video from Super Bowl XXXI.

It took nine years for Max Lane to finally bring himself to sit down and watch the video from Super Bowl XXXI.

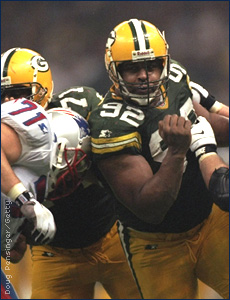

Reggie White's famed hump move overwhelmed many an offensive lineman.

Reggie White's famed hump move overwhelmed many an offensive lineman.

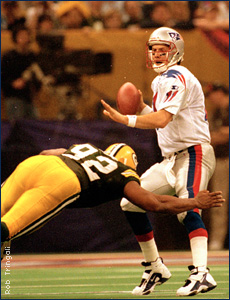

Lane could only watch in horror as White kept getting to Drew Bledsoe.

Lane could only watch in horror as White kept getting to Drew Bledsoe.

White's three second-half sacks of Bledsoe stymied any hopes of a Patriots' comeback.

White's three second-half sacks of Bledsoe stymied any hopes of a Patriots' comeback.

Lane can easily admit: "I was never on Reggie White's level."

Lane can easily admit: "I was never on Reggie White's level."

White's widow, Sara, says Reggie felt those sacks "were his destiny."

White's widow, Sara, says Reggie felt those sacks "were his destiny."

SUPER VICTIMS Part 3

by Eric Neel

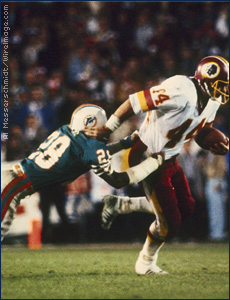

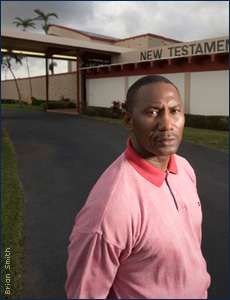

Don McNeal, Cornerback, Miami Dolphins, Super Bowl XVII, Pasadena California

Don McNeal is a true believer. This is evident not only from the fact that he is currently serving as the children's pastor at New Testament Baptist Church in Miami, but also by the fact that on the morning of January 30, 1983, the former Dolphins cornerback was sure his team could win Super Bowl XVII with David Woodley playing quarterback and John Riggins and The Hogs suiting up for the Washington Redskins.

"Absolutely, we were confident," McNeal says. "We had the Number One defense in the league, we had The Killer B's, we were a tight group, we had a great team."

For a long time, the football gods seemed to reward his faith. Woodley hit Jimmy Cefalo for the game's first touchdown in the first quarter and Fulton Walker returned a kickoff 98 yards for six more in the second. The Dolphins led 17-10 at halftime and 17-13 with a little more than 10 minutes left in the fourth quarter.

Then his faith was tested. Well, not so much tested as run over. You know the play: Washington had the ball, fourth-and-one on the Miami 43-yard line, and the handoff was to Riggins. "Miami called a time out before the play," The Diesel says, "and I remember in the huddle thinking that was funny, because we all knew what was going to happen. I knew, there were 90-some thousand people in the Rose Bowl who knew, there were countless millions across the country who knew, and certainly the 11 men on the other side of the line knew. I was getting the ball."

Ever the theatrical one, Riggins thinks back on the moment now and wishes he'd pointed to the left side of the line before the snap, calling his shot like The Babe back in '32. McNeal's recollections begin more technically. "We were in goal-line defense at that particular time," he recalls. "I was supposed to shadow the receiver in motion, Clint Didier, one-on-one." When Didier reversed his field, McNeal spun to keep pace. He slipped and fell, and then scrambled to recover. "[Didier] was ahead of me just a smidgeon when the ball was snapped, he blocked our defensive end, and I replaced, just the way I'm supposed to." And there was Riggins, ball tucked under his right arm, a full head of steam, and eyes angling for the outside. McNeal, coming from Riggins' right, wrapped the big fella up, but he couldn't hold on. Forty-three yards later, the Redskins had the lead and, as it turned out, the Lombardi Trophy.

It happened fast. McNeal had a shot ... and then he didn't. "I could just feel him sort of sliding off me," Riggins says. "And then all of a sudden it was like, 'Gee, I wonder how far I'm going to get.'" Photographs and footage of the play reveal the cornerback's desperation. His fingers claw at Riggins' jersey just above the waist. He reaches feebly up from the ground like one of the damned in Michelangelo's "Last Judgment." "I got my arms around him, but it wasn't enough," McNeal says. "I got my fingernail caught onto his jersey, but he just ripped it off on his way for the touchdown."

Riggins was running down hill at 6-2, 240 pounds. He looked and felt invulnerable. "It was my time," he says. "I could feel that. I was bouncing on the balls of my feet. It was like I'd had a double-shot of espresso with a little grappa on the side." McNeal was a Lilliputian, just 5-11, 185 pounds, and playing catch-up. "He had a glancing shot at me," Gulliver remembers, "but goddang, if I can't make that play, I don't belong in the NFL!"

It wasn't a fair fight. But in the seconds after Riggins broke free, you could tell McNeal didn't see it that way. He rolled over and sat up on the grass, legs bent with an elbow on each knee, like an old man sitting in a rocker on a stoop, and he watched The Diesel tear off down the road. He didn't look defeated like Ralph Branca at the hands of Bobby Thompson, or dazed like Craig Ehlo after Jordan hit the runner, or terrified like Nate Wright, curled at the feet of Drew Pearson and his Hail Mary. He looked dumbfounded. Genuinely surprised. If he'd had a thought bubble floating over his head it would have read, "Well, I'll be a son-of-a-gun ..."

"I had a chance to make a tackle for a loss and get us off the field," McNeal says. "I feel I can make every play I'm confronted by, and I should have made that play. I tackled him too high. If I make that play, we probably win the game"

Forget that the play was damn near impossible. Forget that it would go exactly the same way 99 times out of 100. And appreciate instead the way McNeal, to this day, rises up to meet the scale of the game and the moment. It's on him. He gives the other side their props - "Riggins and The Hogs were awfully tough that day" - but he doesn't shirk, doesn't shrink.

There've been down times, to be sure. Twenty-three years ago, McNeal sat in the post-game locker room in the Rose Bowl, listening to reporters suggest that Dolphins head coach Don Shula cut him, and feeling utterly lost. And like Lane, he's rehearsed the play mentally a thousand times over the years, looking for clues to what went wrong. "It was tough, it was tough, it was tough," he says. "It hurt me to think on it."

But he's embraced the play, too. He'll tell you how it brought him closer to God, because, with something like an ascetic's clarity, he realized while dangling from Riggins' jersey that he was "alone in the world but never alone in his spiritual life." And he'll show you an artist's rendition of the play hanging on the wall in his office at home, because keeping it in a frame reminds him that the play, although it happened in the Super Bowl, is not, finally, the be-all and end-all. It's written in ink, but it's only one chapter. "I don't want to remember the feeling of Riggins getting away," he says, "but the play is just a part of my life. Just a part. It's what happened, but it doesn't define me. I've got to go ahead on."

In fact, the play's gone from being something that mystified him to being something McNeal now puts to good use. It's become a teaching tool in his classes at the church. How will you deal with difficulty? What will you do in the face of loss?, he asks his students. And when they ask him to watch a clip of his showdown with Riggins, or when he stumbles across it on television, he always watches it through to the end.

"I know it sounds funny," he says, "but you know what I always think? I always think I'm going to make the play. I never do, of course, but I'm optimistic."

Intro/Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

E-ticket Archive | ESPN.com | Print | Send to a Friend

Subscribe to ESPN The Magazine

Photo Gallery

Don McNeal was in perfect position to stop John Riggins, but he also was giving up 55 pounds to the Redskins' burly back.

Don McNeal was in perfect position to stop John Riggins, but he also was giving up 55 pounds to the Redskins' burly back.

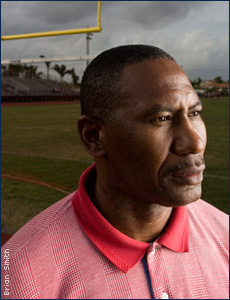

McNeal's failure tested his faith in the years after Super Bowl XVII.

McNeal's failure tested his faith in the years after Super Bowl XVII.

If he'd been able to bring down Riggins, McNeal says his teammates might be wearing a different ring today.

If he'd been able to bring down Riggins, McNeal says his teammates might be wearing a different ring today.

McNeal now uses the Riggins play as a lesson when he instructs kids at his church.

McNeal now uses the Riggins play as a lesson when he instructs kids at his church.

SUPER VICTIMS Part 4

by Eric Neel

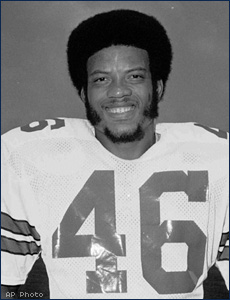

Mark Washington, Cornerback, Dallas Cowboys, Super Bowl X, Miami

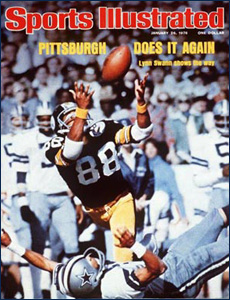

Maybe you have the Sports Illustrated cover on your wall or in your collection somewhere.

It's from January 26, 1976. The headline reads "Pittsburgh Does It Again" and the caption below it says "Lynn Swann Leads the Way." The cover photo is a scene from Super Bowl X.

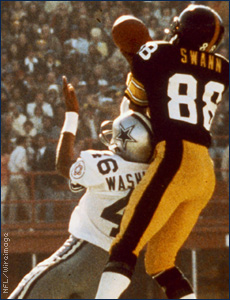

Swann is diving, falling, reaching for the ball on a 53-yard pass from Terry Bradshaw. His hips twist, his legs dangle, his yellow wrist bands and clean white elbow pads are in perfect symmetry, his hands rise up as if in prayer, and you can see his right eye trained on the flight of the ball the way a hitter tracks a fastball coming through the zone. It's been said before, but it bears repeating: The man is the very picture of grace, the Platonic ideal, the essence of receiverness. You look at the photograph, even after you've seen it a hundred times before, and it takes your breath away. He's floating, he's a dancer in the midst of a show-stopping solo.

Except he's not alone. Mark Washington lies beneath him, sprawled, thwacked, blown away, his arms flung over his head like a stick-up victim, his legs shooting up as if they belong to a crash test dummy at the point of impact. He's beaten. He's the poster boy for Beaten. You look at the photograph, even after you've seen it a hundred times before, and you barely even notice him. He's a prop, a part of the background, the stage for Swann's dance.

Half a second earlier, things looked very different. Late in the second quarter, the Steelers were stuck, third-and-six, on their own 10-yard line. The Cowboys were ahead, 10-7. And when the ball came arcing down toward Swann and Washington, it was the cornerback who made the play. "Washington was right there," Swann says. "He tipped the ball away." He put his guys in a position to get a punt and maybe score again before halftime. There was nothing more he could have or should have done. His technique was solid, he timed his jump well, and he broke up the pass. He did not come up short.

Except, of course, he did.

Swann, like Dr. J swooping behind the backboard, somehow stayed aloft and kept the ball alive, planted a knee in Washington's chest, and finally came down with the most spectacular catch in Super Bowl history.

Ask Swann about the play and he speaks with the light touch of a mystic, as if he's afraid to put too much pressure on the memory, as if it might break into a thousand little pieces: "Sometimes during the moment, you see you have to do something different and you have to figure out, sometimes in the moment, what that something different is."

Ask Washington about the play and you get nothing airy or philosophical at all. He keeps it grounded, keeps it simple and real: "The guy made a play. I was in position to some extent, but I didn't make the play."

"The guy" - not Swann, not Lynn, but "the guy." There's a safe distance in saying "the guy," and a certain no-quarter competitive fire. On some level, 30 years after the fact, Washington's still pissed at the way the play turned out. Part of that anger might be reserved for the late Tom Landry and defensive coordinator Ernie Stautner. As much as Swann, they were responsible for the position in which Washington found himself. First, they misread the Steelers' attack in the days leading up to the game by more or less ignoring Swann, John Stallworth, Terry Bradshaw and the Pittsburgh passing game. Swann had suffered a concussion in the AFC Championship game against the Raiders, and it was uncertain whether he would play in the Super Bowl at all (he decided to play when Cowboy safety Cliff Harris told reporters Swann might get hurt if he suited up). The Cowboys' emphasis was on Franco Harris and the running game. "Our main thing all week was stop the run," Washington says. "I think Tom's strategy was that he didn't want you to control the ball on him. I don't know that we really focused that much on the passing aspect of the game." Second, the Dallas coaching staff was in love with the blitz when the Steelers passed. "I think our major flaw that day was we got into these situations where we max blitzed the quarterback and it didn't work," Washington says. "When you're talking about a max blitz situation, that means everybody going except the cornerback, safety included. So I had to run 40, 50 yards with the guy one-on-one."

And it wasn't just the one play. There was a 12-yard completion to the right sideline in the middle of the third quarter, and there was another bomb. This one came in the fourth quarter, on third-and-four from the Steelers' 36. Again the Cowboys blitzed all-out, and this time linebacker D.D. Lewis got to Bradshaw (knocking him unconscious), but not before he let loose a prodigious spiral down the middle of the field. "We could get away with blitzing some teams, maybe," Washington says. "But Bradshaw had a real strong arm, and he picked up everything we threw at him." The ball, Swann and Washington flew down the field together. Sixty-four yards later, it was déjà vu all over again. Washington, this time maybe half a step behind Swann, reached up and tapped the ball. Swann, unfazed, pulled it in over his left shoulder for a running touchdown. He barely broke stride. "In terms of coverage, Mark Washington had a great day," Swann says. "I just had a little something extra." And that something extra was the difference in the game; the 64-yarder put the game away, 21-10 Steelers.

Like McNeal, Washington fantasizes about things turning out differently, about Swann dropping one or both of those balls, but he isn't haunted by the plays. "I see them on TV all the time this time of year," he says. "It's not something I run from. I take responsibility for what happened. It's my job to make the play, regardless of the circumstances." The interesting thing about the highlights, he thinks, is the chance to see something that happened in a flash drawn out in slow-motion. In slo-mo the mind allows for possibilities and imaginary decisions unavailable in real time. In slo-mo, Washington wonders whether he should have tried for an interception on the first pass, instead of just knocking the ball down, or whether maybe he should have jumped higher to make a play on the second one. "You go back and you can invent a whole lot of things," he says. "There's a lot of second-guessing."

But when he might give in to doubt and regret, Washington rights himself. "I give the guy credit, he went above and beyond," he says. "It's nothing I feel great about, but if you play, and you call someone to perform above and beyond, that's what Super Bowls are about."

A bit of philosophy after all: He and the guy weren't just adversaries - they were partners.

Intro/Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3 | Part 4

E-ticket Archive | ESPN.com | Print | Send to a Friend

Subscribe to ESPN The Magazine

Photo Gallery

Lynn Swann's acrobatic catch -- and Mark Washington's worst nightmare -- were memorialized forever on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

Lynn Swann's acrobatic catch -- and Mark Washington's worst nightmare -- were memorialized forever on the cover of Sports Illustrated.

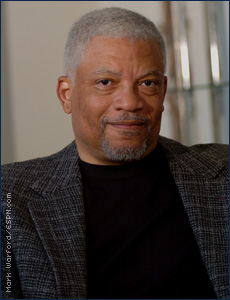

Washington still fantasizes about things turning out differently.

Washington still fantasizes about things turning out differently.

"You go back and you can invent a whole lot of things," Washington says. "There's a lot of second-guessing."

"You go back and you can invent a whole lot of things," Washington says. "There's a lot of second-guessing."

Even 30 years later, Washington still refers to Swann as merely "the guy."

Even 30 years later, Washington still refers to Swann as merely "the guy."

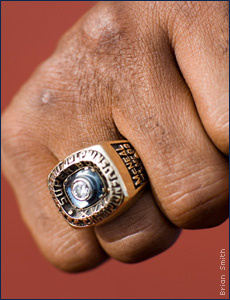

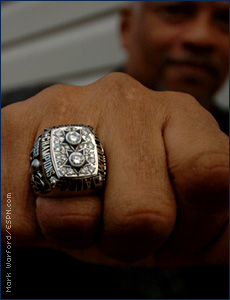

Washington shows off his NFC Championship ring, but he was denied the top jewel in 1976.

Washington shows off his NFC Championship ring, but he was denied the top jewel in 1976.