|

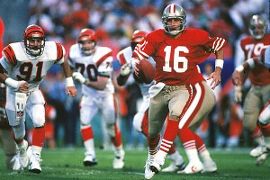

NEW ORLEANS -- New Orleans Saints coach Sean Payton entered halftime of Super Bowl XLIV feeling like it was time to take a chance. He had spent the first two quarters of that contest watching the Indianapolis Colts grind out a 10-6 lead, and the momentum clearly favored the opposition. The Colts had won a championship just three years earlier. They knew how to close out an opponent still learning how to handle football's biggest stage. So after meeting with his assistants, Payton decided it was time for a gimmick: an onside kick to start the second half. He had hoped to use that bit of trickery in the NFC Championship Game win over Minnesota, but the right opportunity never presented itself. In Miami, with the Super Bowl hanging in the balance, Payton understood it was time to roll the dice. "We were psyched when he called it," said reserve safety Chris Reis. "With Peyton Manning on the other side, we knew we had to steal a possession. We really didn't think [Payton] would ever use it, but he liked to have things like that in his back pocket. He obviously went to it at the right time."  That onside kick -- one that Reis ultimately recovered -- proved to be the game-changing play in a contest the Saints eventually won. It's also the perfect example of how critical such instinctive decisions can be when football's ultimate prize is on the line. It's no mystery that the Super Bowl is a game like no other, the dream that all coaches pursue from the moment they enter the sport. What those same men often don't realize -- at least not until they're actually in that game -- is how challenging it can be to do the little things that ultimately determine winning and losing. When the Baltimore Ravens and San Francisco 49ers line up for Super Bowl XLVII, they surely will have heard plenty of advice about how to handle that day. They really won't know how little that means until they're facing that environment themselves. "It still all boils down to a football game," said Dick Vermeil, who lost a Super Bowl while head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles and won one with the St. Louis Rams. "But you don't realize that until the game actually kicks off. That's why you win with the preparation you put in before the game. You have to rely on that." That's easier said than done when it comes to game day. When Vermeil's St. Louis team met the Tennessee Titans in Super Bowl XXXIV, he spent much of the pregame visiting with players individually and chatting with close friends he had invited to the event. Vermeil hated being at the stadium so early -- teams usually arrive three hours before kickoff instead of two -- and he had to find ways to relax his nerves. The last thing he wanted was for anxiety to factor into his decision-making. Vermeil fully understood all the chaos that surrounds that day. Photographers and celebrities jam the sidelines. The energy in the stadium feels strange because the stands are largely filled with fans who aren't partial to either team. As former Colts linebacker Gary Brackett said, "There's literally no space to move around down there. And on top of everything else, you know the whole world is watching and second-guessing what you do." Even the most successful coaches can have a hard time operating under such circumstances. Consider former Green Bay Packers head coach Mike Holmgren. When his team faced the Denver Broncos in Super Bowl XXXII, he ordered his defense to concede a tiebreaking touchdown to the Broncos with 1:45 left in that contest. Holmgren knew he had to preserve the clock and his timeouts to pursue a game-tying touchdown. What he didn't realize was that it was second down from his 1-yard line when he ordered his team to stand down.  Holmgren later admitted it was a mistake to give up the touchdown in that situation -- he thought it was first down -- but that his ultimate plan was to create an opportunity for his offense. He told reporters at that time that "we made the decision. I wanted the ball back. I thought our best chance was to have our timeouts left with 1:45, so I just told them to let them score. ... It was a strategy I felt was our only chance to win." "Every move you make in that game is so critical," said former Packers safety Mike Prior. "With the pace of that game, and with everything going on around you, it can be tough to make some of those calls. In that situation [Holmgren was in], you have to wonder if people are really prepared for that. You're thinking about the down, the time left, your timeouts, how you're going to score, and you're talking about letting your defense give up a touchdown, which is a rare move in itself. I can see why he got distracted." Of course, Holmgren wasn't the only coach to have such issues in the heat of such a huge moment. Pittsburgh Steelers defensive coordinator Dick LeBeau -- who is widely considered one of the smartest defensive minds in the game's history -- had a rough night when he coached Cincinnati's defense against San Francisco in Super Bowl XXIII. That game is best known for the 92-yard drive that ended with 49ers quarterback Joe Montana hitting John Taylor for the winning touchdown. But that legendary Super Bowl moment might not have happened if LeBeau had listened to his fellow assistants during the possession. Defensive coaches pleaded with LeBeau to alter his schemes as the 49ers moved up the field, according to one team source. They specifically wanted LeBeau to double-cover 49ers wide receiver Jerry Rice, who was on his way to an 11-catch, 215-yard performance. LeBeau responded by sticking with the same defense -- a Cover 2 look with four down linemen and two linebackers -- that gave Montana ample opportunity to make history. "Dick actually apologized for that after the game was over," the team source said. "Here's one of the greatest defensive coaches ever, and even he choked in the Super Bowl."  It's not hard to see why such mistakes can occur in the Super Bowl. The entire event is chaotic from the minute the opponents arrive in the host city. It can be overwhelming for players to find tickets for loved ones, face a relentless media barrage and try to ignore the urge to party too much. The real challenge, however, is managing and monitoring the way players prepare for the actual game day. Dan Reeves appeared in an NFL-record nine Super Bowls as a player and coach -- including three losses as head coach of the Broncos and a fourth with the Atlanta Falcons -- and he still feels the pain of missed opportunities. "When you don't win, you have a tendency to say you tried this or that and it just didn't work," Reeves said. "No matter how big the game is, it still comes down to getting players prepared to play. That's my frustration as a coach. We never got our players to play as well as they could on that day." Some of the challenges that appear on game day are difficult for coaches to control. For one thing, the amount of time spent waiting to play can feel endless. "The day of the game isn't like a regular game, especially in the pregame," said Steelers offensive coordinator Todd Haley, who held the same job with the Arizona Cardinals during Super Bowl XLIII. "Everybody has a routine that they've used throughout the year, but it's easy to get caught up in the hoopla. You're out there on the field, and the next thing you know people are coming up to you or celebrities are preparing for their routines. And before you know it, you're getting ready to start the game. There are a lot of potential distractions that come up on that day." That extra time also can lead to major fatigue. A typical NFL game lasts around three hours, but a Super Bowl can run anywhere from four to 4½ hours. Many players and coaches aren't adequately prepared for the mental strain that comes from staying focused for so long and dealing with a contest that, as Haley said, "moves so fast that you feel like it's done in the blink of an eye." Some don't even recognize the challenge until long after the game has ended. They've already had two weeks to think about playing the game, and now they have to keep their minds on the task at hand. "You can't let the magnitude of the game affect your decisions," said former Cardinals head coach Ken Whisenhunt, who recently became the San Diego Chargers' offensive coordinator. "You've played 20-plus games [including the preseason] to get that point, so you have to stay true to what you've done. You obviously know it's the Super Bowl, but you're likelier to make a mistake if you start worrying about trying to avoid one."  ESPN analyst and former NFL head coach Herm Edwards, who played for Vermeil during the Eagles' 1980 Super Bowl season, added that many teams struggle during the game because they enter it with too much preparation. He joked about his experience with the Eagles -- "We won the game on Thursday even though we didn't actually play it until Sunday," he said -- but there is ample opportunity for coaches to fall into the trap. The temptation to keep tinkering with the game plan during the two-week layoff is huge, as is the desire to continually analyze film. While most coaches usually look at three game tapes during a typical regular-season week, they can easily double that amount with the extra time at their disposal. Those same possibilities creep up during the 30-minute halftime. (Teams normally get 12 minutes during the regular season.) When the Cardinals faced the Steelers in Super Bowl XLIII, Whisenhunt made sure players had plenty of food available and ample time to relax. "I had pages of notes from talking to coaches like [former Steelers coach] Bill Cowher and [Patriots head coach] Bill Belichick," Whisenhunt said. "I knew what to expect and how to prepare for the long waits. Whether it was giving guys some extra stretching before the game or more food at halftime, the key was communicating to the players what to expect." The Cardinals ultimately used that time to their advantage, but they did suffer from concentration lapses in that contest's final minutes. One former assistant said Cardinals coaches told cornerback Dominique Rodgers-Cromartie three different times that the Steelers were going to run a play in his direction that involved a curl by an outside receiver and a flag route by an inside receiver. All they asked was that Rodgers-Cromartie not bite on the shorter pattern, which would leave the deeper route open. So what did Rodgers-Cromartie do? He jumped the curl route every time the play was called, a mental lapse that ultimately led to Santonio Holmes catching the winning touchdown pass from Ben Roethlisberger. All fans saw was Holmes snaring the ball in the back of the end zone before falling out of bounds. The Cardinals' defensive coaches saw their best chance at a championship evaporate because their top cornerback couldn't follow instructions. That's the potential rub every coach faces in the Super Bowl. Even when their players are properly prepared for the critical situations, they might not execute in the way coaches had hoped. The most carefully constructed plans can be tainted by an ill-timed lapse in judgment. In the process, a lifetime dream can become a cruel memory that lingers for years, if not decades. Given the similarities between the Ravens and 49ers -- and the fact that brothers Jim (San Francisco) and John (Baltimore) Harbaugh are the head coaches -- it's quite likely that this game will be impacted by a comparable decision. Another factor will be the teams' ability to settle into the game and not allow it to be something that's too big for them. Vermeil said he didn't really appreciate how hard that task was until he was in his second Super Bowl. "I was more mature the second time around," he said. "Not everything bugged me, and what I realized is that you can't really appreciate winning that game until you've lost." Brackett added that the coaches who best understand how to handle the urgency of the moment are the ones with the optimal chances of winning. He was on the opposing sideline when Payton called that onside kick and, like his teammates, he had been caught off guard. Brackett had been ambling around his team's sideline, hoping like crazy to find a way to stay loose for the third quarter. Once Reis recovered the kick, Brackett knew Payton had delivered the kind of masterstroke that alters legacies. "If we'd recovered the football in that situation, we'd be talking about a totally different Super Bowl," Brackett said. "But that's how it goes in that game. You have to respect the moment, and you have to be ready to capitalize on it. That's what they did."

|