|

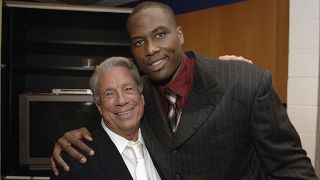

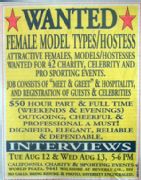

This story ran in the June 1, 2009 issue of ESPN The Magazine. Donald Sterling looks good. The 76-year-old billionaire owner of the Clippers always looks good, an occasional tousle of salt-and-cinnamon hair dangling over his expressive, perpetually tanned face. Sweeping into the Millennium Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles the night of May 14 wearing a black suit and white tie, he directs photo ops before commenting to his companions about a Mag reporter: "Do you know why they're here? They want to know why the NAACP would give an award to someone with my track record!" For more than two years, Sterling has been staring down federal civil rights charges related to his real estate holdings and rental practices. According to the Justice Department, Sterling, his wife and three of his companies have engaged in discrimination, principally by refusing to rent to African-Americans. In February, Elgin Baylor, the Clippers GM from 1986 to 2008, filed an age and racial discrimination suit against his old boss alleging, among other things, that Sterling repeatedly expressed a desire to field a team of "poor black boys from the South ... playing for a white coach." Sterling's attorneys have denied the accusations. And even as these controversies swirl around him, Sterling is here tonight to receive a lifetime achievement award from the local chapter of the NAACP. The man of the hour ushers two black guests over to talk to the reporter. "Donald Sterling is a prince among men," says Leon Isaac Kennedy, who starred in the Penitentiary series of movies in the '70s and '80s. "I've been his friend for 25 years." At dinner, the emcee updates the crowd on the Lakers, who are losing to Houston in a crucial playoff game. With Sterling in attendance, guests aren't sure whether to boo or cheer. But when the Clippers owner rises to speak, he is gracious. "I really have a special feeling for this organization," he says. He's a major donor, contributing $10,000 to $15,000 this year alone, according to chapter president Leon Jenkins. Sterling doesn't stay to hear all the speakers -- his entourage is at the hotel bar watching the game -- but while speaking, he holds his two-handled trophy cup aloft. And he smiles that smile, the almost smirk you see in photo after photo of the man associates call The Donald. It's smooth and self-satisfied and says not just that the guy behind it makes his own rules but that he's won yet another round. Tell him he can't move his team, and he'll move it anyway. Complain that he's a cheapskate, and he'll spend just enough to maintain the profit margin he wants. Sue him for sexual harassment or housing discrimination, and he'll buy your silence with a hefty cash settlement. Call him a racist, and he'll show you an eminent civil rights organization lauding his accomplishments. As for his franchise? Well, there are two kinds of basketball fans: those who know the details of its sad history and those who don't need to. Suffice it to say that 2008-09 marks the seventh time the Clippers have lost 60 games in a season and the 17th time they've lost 50 since Sterling moved them to Los Angeles 25 years ago, both achievements unequaled by any other team in the league over this period. The Clippers have reached the second round of the playoffs just once in that time, going 701-1,317 overall, for a .347 winning percentage that is easily the worst among the four major sports. Horrible trades, disastrous drafts, endless injuries -- with Sterling at the helm, the Clippers and their faithful have been through it all, again and again. Not that Sterling is happy to fail. As recently as March 2, after a home game in which the Clippers were blown out by the Spurs 106-78, he barreled into the locker room and cursed out his club. One player who didn't recognize his employer reportedly thought about calling security. "It's a total frustration for him," says Hollywood producer Michael Selsman, who's known Sterling since 1962. "People probably think he has a less-than-firm commitment to winning, when he's actually consumed with it." But while owning a team hasn't brought him a title, it has given Sterling something he seems to value more: the power to be heedless. "Just evict the bitch." It was 2002, and Donald Sterling was talking to Sumner Davenport, one of his four top property supervisors, about a tenant at the Ardmore Apartments. Already the largest landowner in Beverly Hills, Sterling had recently acquired the Ardmore as part of his move to extend his real estate empire eastward toward Koreatown and downtown LA. As he did, Sterling "wanted tenants that fit his image," according to testimony Davenport gave in a discrimination lawsuit brought against Sterling in 2003 by 19 tenants and the nonprofit Housing Rights Center. (That case ended in a confidential settlement in 2005; attorneys for the Center declined to comment for this story. In a separate suit, also concluded in 2005, Davenport claimed Sterling sexually harassed her, and lost. She declined comment. The Magazine has obtained depositions in both cases.) Cultivating his image, Davenport said, meant no blacks, no Mexican-Americans, no children (whom Sterling called "brats") and no government-housing-subsidy recipients as tenants. So according to the testimony of tenants, Sterling employees made life difficult for residents in some of his new buildings. They refused rent checks, then accused renters of nonpayment. They refused to do repairs for black tenants and harassed them with surprise inspections, threatening residents with eviction for alleged violations of building rules. When Sterling first bought the Ardmore, he remarked on its odor to Davenport. "That's because of all the blacks in this building, they smell, they're not clean," he said, according to Davenport's testimony. "And it's because of all of the Mexicans that just sit around and smoke and drink all day." He added: "So we have to get them out of here." Shortly after, construction work caused a serious leak at the complex. When Davenport surveyed the damage, she found an elderly woman, Kandynce Jones, wading through several inches of water in Apartment 121. Jones was paralyzed on the right side and legally blind. She took medication for high blood pressure and to thin a clot in her leg. Still, she was remarkably cheerful, showing Davenport pictures of her children, even as some of her belongings floated around her. Jones had repeatedly walked to the apartment manager's office to plead for assistance, according to sworn testimony given by her daughter Ebony Jones in the Housing Rights Center case. Kandynce Jones' refrigerator dripped, her dishwasher was broken, and her apartment was always cold. Now it had flooded. Davenport reported what she saw to Sterling, and according to her testimony, he asked: "Is she one of those black people that stink?" When Davenport told Sterling that Jones wanted to be reimbursed for the water damage and compensated for her ruined property, he replied: "I am not going to do that. Just evict the bitch." Repairs never came. The shower stopped working, and the toilet wouldn't flush; Jones needed to use a plunger and disposed of waste tissue in bags. Kandynce Jones departed the home she loved but that caused her so much grief when she passed away, on July 21, 2003, at age 67. Two years later, Sterling resolved the Housing Rights Center case with a payout. The details of the agreement are confidential, but U.S. District Court judge Dale Fischer called the settlement one of the largest ever obtained in this type of case." Plaintiffs were awarded $4.9 million in legal fees alone. In August 2006, the Justice Department hit Sterling with the federal housing discrimination charges he faces today. They portray a pattern of behavior far in spirit from the starlit world of Spago and Staples that Donald Sterling revels in publicly. Donald Tokowitz was born to immigrant parents in 1933. He grew up in Boyle Heights, a tough, low-income East LA neighborhood where his father, Mickey, was a produce dealer. Susan, his mother, emphasized the value of education, and the young Donald excelled at Roosevelt High, where he was elected class president and made the city gymnastics finals. He stayed in public schools, attending Cal State-Los Angeles and Southwestern Law School, paying for classes by taking a sales job at Harry Stein's Coliseum Furniture. He married the owner's daughter, Shelly. (They have been married 51 years and have three children.) He also changed his name, telling a fellow salesman, according to Los Angeles Magazine, "You have to name yourself after something that's really good, that people have confidence in."  The newly minted Donald T. Sterling launched his career as a personal injury and divorce attorney in 1961, doggedly building an independent practice at a time when, as a Jew, he had no shot at working for most prestigious law firms. A tireless advocate, Sterling once estimated that he'd tried 10,000 cases. With the money he earned he began to invest in real estate, and with an instinct for hoarding common among Depression-era children, he was a natural buy-and-hold investor at the perfect time for buying and holding West Coast property. Beginning in the 1960s, when the California market was depressed, he acquired scores of apartments between Beverly Hills and the Pacific Ocean, and he hardly ever sold. "I never purchase anything I don't think I'm going to keep for a lifetime," Sterling, who declined to be interviewed for this story, said to Los Angeles Magazine in 1999. When prices went down, he bought more. When they rose, he refinanced. All the while, millions of Americans were moving to Southern California, making LA landlords very rich men -- few richer than Sterling. In the 1970s, Sterling got to know Jerry Buss, then a chemist who was also an LA real estate investor. In May 1979, Buss was set to buy the Lakers, but 15 hours before the purchase deadline he was still $2.7 million shy of the needed cash. So he called Sterling, who covered part of the shortfall by buying a group of 11 Santa Monica apartment buildings from Buss. Soon after, the San Diego Clippers were on the block, and Buss suggested his pal buy them. And so in 1981, Sterling acquired the franchise for $12.7 million. Those San Diego years are the stuff of NBA legend. Sterling welcomed himself to town by plastering his face on billboards across the city. And when the Clips won their 1981 home opener, he ran across the court, shirt unbuttoned and glass of wine held aloft, to high-five his players and hug coach Paul Silas. "I love you!" he told them. But later that year he refused to pay a $1,000 prize to a local lawyer who won a free throw contest until the guy sued for fraud. Sterling even asked Silas to cut costs by taping players himself. Before the next season, he installed an ex-model named Patricia Simmons as assistant GM, putting her at Silas' desk while the coach was on an NBA promotional trip to China. Silas returned to find his belongings piled in the hallway. And it was in San Diego that Sterling first employed the money-saving tactic of declining to replace injured Clippers; the team nearly forfeited one game when a player's emergency dental work temporarily left them with just seven able bodies. In 1984, Sterling moved the team to LA. The NBA, sensitive to charges that teams were abandoning fans -- and trying to control franchise locations -- fined him $25 million. When he countersued for $100 million, the league blinked, cutting the penalty to $6 million, then allowing Sterling to pay it out of his share of expansion fees rather than his own funds. He dropped his suit and eventually ended up on the committee that gave David Stern a $30 million extension. The Clippers moved into the Los Angeles Sports Arena, a facility so outdated that the Lakers had abandoned it nearly 20 years earlier. But even though the team averaged fewer than 8,500 fans per game in its first three years in LA -- among the worst attendance in the league -- that was almost double the team's draw in San Diego. Plus, the arena charged the Clippers just a few thousand dollars per game in leasing fees, making profitability easy. Even better, Sterling was in his hometown with a pro sports franchise in his portfolio, providing a public profile he'd never enjoyed. Tycoonship had other rewards: After moving his headquarters to a seven-story Beverly Hills Art Deco building erected by MGM Studios mogul Louis B. Mayer, for example, Sterling had it renamed Sterling Plaza, took over the top two floors--then refused to rent the remaining floors to anyone else, famously enjoying his solitary elevator rides. And now he made noise with his parties: "Summer whites, champagne and caviar," recalls current Comcast-Spectator president Peter Luukko, who managed the Sports Arena when the Clippers were tenants. "Doctors, sponsors,movie stars and the Clippers dancers running around. It was like, 'Hello, Hollywood.' " Sterling's Tinseltown fantasy, though, didn't extend to investing much more in his team than he had in San Diego. Throughout the '80s and '90s, he didn't sign a single significant free agent. Instead, the franchise regularly picked players high in the draft -- Michael Cage, Danny Manning, Lamar Odom -- only to develop them for a while before letting them go. Some insiders saw his strategy as something more insidious than mere bargain-hunting. Baylor says that because he tried to pay African-American players such as Cage fairly, Sterling restricted him from negotiating with them; eventually, Baylor contends, the owner told his GM not to talk to players or agents about money at all. Baylor also alleges that when the Clippers got bogged down in negotiations with Manning, Sterling said, "I'm offering a lot of money for a poor black kid." (Clippers general counsel Robert H. Platt responded in a statement that Baylor's "false claims carry no weight and have no credibility," saying his lawsuit is "driven by publicity-seeking attorneys.") All the while, Sterling was building a reputation as an invasive but indecisive owner. Classic example: In 1993, Manning, then an unhappy All-Star, asked Sterling why he wasn't dealt at the trade deadline. Sterling replied that he'd dreamed the Clippers had won a championship after he'd passed the ball to Manning for the winning shot. The following year, though, Manning was dumped for an over-the-hill Dominique Wilkins. "Dealing with Sterling was impossible," Carl Scheer, the team's GM from 1984 to 1986, once said. "If he took the elevator down, he'd ask the operator what he thought, and by the time he had reached the lobby, he'd changed his mind." Win or lose or lose or lose, though, Sterling is a courtside presence, rubbing elbows with lower-rung celebrities who aren't in the Lakers' orbit: Roseanne Barr, Donna Mills, George Segal. ("Billy Crystal is the gold standard of that crowd," says one longtime Clippers observer. "But he doesn't always sit with Sterling. He has his own seats.") Sterling even used to hold lottery parties at his Beverly Hills mansion (formerly owned by Cary Grant), where D-list actors and buxom hostesses could watch the Clippers' annual shot at getting a high draft choice. In 1990, the team landed the eighth pick. "Well," said Alan Rothenberg, then the team's general counsel, "think about how much money we just saved!" The guests then returned to wondering if Pia Zadora's double-parked Mercedes would get towed. "I like people who are achievers," Sterling once told the Los Angeles Times. "This is a town where the entertainers work. Where you can call anybody like you've known them for a lifetime and ask them to be a special guest." Sterling himself has become a celebrity in a town that worships notoriety like no other. He's even achieved a kind of Superfriends status among renegade sports owners, befriending the likes of Al Davis and Jerry Reinsdorf, with whom he had lunch at the Super Bowl in 2008. (Neither man agreed to comment for this story.) Owning the Clippers has yielded tangible benefits, too. For one thing, Forbes estimates that the team is now worth $297 million. Sterling's huge gain is the direct result of the buy-and-hold strategy that made him rich in real estate. He entered the league just as Bird, Magic and MJ were triggering an explosion in revenues, and media rights fees have risen steadily ever since. His Clippers get an equal share of the league's TV and digital cash, about $31 million this year, whether or not they are ever on national TV. In any other industry, another company would have swooped in by now to undercut Sterling, offering a better product at lower prices. But sports teams are monopolies -- or, in the case of the Lakers and Clippers, duopolies -- protected by their leagues from competition. So despite continually woeful performance, the Clippers are now worth 23 times what Sterling paid. Moreover, since moving to Staples in 1999, the Clippers have turned big profits for Sterling each year. With their perpetual losing and in the shadow of the Lakers, they generate relatively little money from ticket sales, premium seats and signage, and their overall revenue of $99 million in 2007-08 ranked 25th in the NBA. But that's still far more than they ever made at the Sports Arena. They also have no debt and a fairly low payroll -- despite some increased spending in recent seasons at the urging of coach Mike Dunleavy. They have low rent, too. The Staples Center's chief executive, Tim Leiweke, has said his building would make more money from five concerts than from a whole slate of Clippers games. But to guarantee the certainty of the team's revenue stream, he let Sterling renew his lease in 2004 for just $1.5 million a year. Add it all up, and in the nine years after moving into Staples, the team made $140 million in profits. The Lakers, who spend money on an entirely different scale and win about twice as often, made $322 million over that time. But the Mavericks, another high-spending big winner, lost $137 million. Sterling runs a low-risk, sure-reward game. Who's going to tell him he's wrong? At his best, Sterling can make you believe anything is possible. He has an infectious grin, boyish enthusiasm and a propensity for hugs and shoulder rubs. His willingness to say everything with conviction can seem downright Clintonian, but it also registers as optimistic. "I thought there was no way the Clippers were going to match the contract I signed with the Heat in 2003. I was in the Mandarin Oriental Hotel in Miami when Donald Sterling called," says Elton Brand. "He said, 'I love you, I love Elton Brand.' I was surprised but honored. He honestly feels what he feels at that time."  But Sterling also uses his wealth and power like many other rich and powerful men: to impose his eccentricities on others. When dining out, Sterling has on occasion recommended meals for his guests without ordering anything for himself, forcing them to then share with him. He once invited a draft pick to his Beverly Hills mansion, then conducted the meeting wearing only a bathrobe. He also regularly makes large contributions to charities -- like the Special Olympics -- and then when the groups honor him, he takes out self-congratulatory newspaper ads. "Sterling desperately wants people to believe he's a good person, and if they don't, it drives him crazy," says a lawyer who knows him. "But he also just can't get out of his own way." In 2006, Sterling announced plans to build a sprawling homeless-services center in the midst of LA's Skid Row. One newspaper ad for the project showed a vacant-eyed redheaded child, whom locals took to calling Zombie Girl. Another declared that the Donald T. Sterling Charitable Foundation would develop a "state-of-the-art $50 million dollar [sic]" project for "over 91,000 homeless people." It featured a photo of a smiling Sterling above the quote "Please don't forget the children, they need our help." But while Sterling spent $8.4 million to buy several properties at Sixth and Wall streets, he has yet to move forward with his plans to help the homeless. Some advocates now believe that Sterling is waiting for them to foot the cost of the center. Others suspect he may never build it at all, and has bought the land, as he's done so often, simply because he expected the area to gentrify and its value to rise. But it's the people who work for Sterling and live in his buildings who say they bear the worst of his unconventional behavior. For years he has run semianonymous ads (crude design jobs he reportedly mocks up himself) seeking "hostesses" for Clippers events and his private parties. In a Times ad last summer, Sterling's company solicited "attractive females" to bring a résumé and photo to his address, where employees reviewed their looks. Some of the women who have gone through this process found it humiliating. "Working for Donald Sterling was the most demoralizing, dehumanizing experience of my life," says a hostess from the 1990s who says she helped set up "cattle calls" to find other women to work the job. "He asked me for seminude photos and made it clear he wanted more. He is smart and clever but manipulative." "When I didn't give him what he wanted, he looked at me with distaste. His smile was so empty." In 1996, a former employee named Christine Jaksy sued Sterling for sexual harassment. The two sides reached a confidential settlement, and Jaksy, now an artist in Chicago, says, "The matter has been resolved." But The Magazine has obtained records of that case, and according to testimony Jaksy gave under oath, Sterling touched her in ways that made her uncomfortable and asked her to visit friends of his for sex. Sterling also repeatedly ordered her to find massage therapists to service him sexually, telling her, "I want someone who will, you know, let me put it in or who [will] suck on it." Jaksy first worked for Sterling in 1993, as a hostess at one of his "white parties," where guests dressed Gatsby style at his Malibu beach house; she eventually went into property management. Jaksy testified that Sterling offered her clothes and an expense account in return for sexual favors. She also testified that he told her, "You don't need your lupus support groups...I'm your psychiatrist." Jaksy left her job in December 1995, handing Sterling a memo that read in part, "The reason I have to write this to you...is because in a conversation with you I feel pressured against a wall and bullied in an attempt to be overpowered. I'm not about to do battle with you." She carried a gun because, according to her testimony, she feared retribution. In February 1997, though, Sterling denied her charges under oath, and his lawyers portrayed Jaksy as unstable. Testifying in a different case six years later, Sterling said he had no recollection of the name Christine Jaksy, didn't recall ever being involved in litigation with her and didn't know of any woman ever having sued him for harassment. Sterling's testimony in another case, this one involving former associate Alexandra Castro, underscores his aggressiveness with women. When Castro, whom Sterling met in Las Vegas at Al Davis' birthday party over Fourth of July weekend in 1999, visited his Beverly Hills office, Sterling later stated under oath that she brought a lab report proving she was HIV-negative, freeing him to continue having unprotected sex with his wife. "The woman wanted sex everywhere," Sterling said. "In the alley, in her car, in the elevator, in the upstairs seventh floor, in the bathroom." And he paid her for it. "Every time she provided sex she got $500," he testified in 2003. "At the end of every week or at the end of two weeks, we would figure [it] out, and I would, perhaps, pay her then." "When you pay a woman for sex, you are not together with her," he further testified. "You're paying her for a few moments to use her body for sex. Is it clear? Is it clear?" Sterling's affair with Castro nearly exploded after he took back a $1 million Beverly Hills property she claimed had been a gift. They wound up squabbling in court, where they ultimately reached a confidential settlement. When it comes to female subordinates in his real estate business, Sterling shows a distinct racial preference. In 2003 he had 74 white employees, four Latinos, zero blacks and 30 Asians, 26 of them women, according to his Equal Employment Opportunity filings with the state of California. (The numbers are similar for the other years in which Sterling has been charged with racial discrimination.) "He would tell me that I needed to learn the 'Asian way' from his younger girls because they knew how to please him." Davenport testified in 2004. Davenport also stated: "If I made a mistake, I needed to stand at my desk and bow my head and say, 'I'm sorry, Mr. Sterling. I'm sorry I disappointed you. I'll try to do better.' " Sterling's preference for Asians extended to the people he wanted in his buildings. "I like Korean employees and I like Korean tenants," he told Dean Segal, chief engineer at a Sterling property called the Mark Wilshire Tower Apartments, according to testimony Segal gave in the Housing Rights Center case. And Davenport testified that Sterling told her, "I don't have to spend any more money on them, they will take whatever conditions I give them and still pay the rent...so I'm going to keep buying in Koreatown." At the Towers, Sterling's staff issued applications for garage-door remote controls that required residents to disclose their birthplace and national origin. Darren Schield, controller at Beverly Hills Properties, later denied that Sterling wanted the information to screen tenants by race. Instead, he said, "sometime after Sept. 11, 2001," an FBI special agent warned that several tenants who were "foreign, I mean as Muslim, or, you know," were targets of Bureau investigations. Even more bizarre but just as effective at driving away African-Americans and Hispanics, Beverly Hills Properties changed the name of the Wilshire Towers complex to Korean World Towers. A huge banner printed entirely in Korean was hung on the building, and the doormen were replaced by armed, Korean-born guards who were hostile to non-Koreans, again according to testimony given by multiple residents.  In August 2003, during the Housing Rights Center lawsuit, a federal judge ordered Sterling to stop using the word "Korean" in the names of his buildings, but the damage had been done. "Even to this day, I still feel leery that at any given point we could be evicted," testified tenant Aubrey Franklin. "[It's] not pleasant to live in a community...[where] the spirit and the camaraderie [are] gone." It's clear why Donald Sterling stays in the game: He's got celebrity, money and the freedom to do as he pleases, in basketball and in business. And no one outside government looks especially interested in making him change his ways. With litigation ongoing, the Justice Department has no comment on Sterling's actions as a landlord. The NBA also has nothing to say about the owner's legal battle with Baylor or those federal charges. "It would be premature to have any real take on it," says league spokesman Tim Frank. Asked to compare the hands-off treatment of Sterling with the $25,000 fine dropped on Mavericks owner Mark Cuban for Twittering about referee calls, Frank replies, "There's a big difference between business decisions and personal attacks." Other owners don't mind Sterling: He's entertaining in meetings, and his team is so bad that other clubs pick up an extra win or two a year as long as he's around. "I like Donald," says Cuban. "He plays by his own rules." And the Lakers aren't bothered by their shabby co-tenants; they get first dibs on Staples dates. This season the Lakers played 22 games on Fridays or Sundays, versus nine for the Clippers. Even team executives who have spoken out on racial issues show no inclination to take on a current owner. Arthur Triche, a Hawks VP and the first African-American to head an NBA team's public relations office, recently called for a boycott of Lenny Dykstra's new magazine Players Club after GQ quoted the former baseball player making bigoted comments. But this is what Triche says about Sterling's alleged discriminatory practices: "I'm not fully abreast of the situation, and I don't need to get into that. It doesn't impact how I do my job." The people who have sued Sterling have almost all accepted payouts in return for silence. "You may be convinced you can win, but at the end of the day, nobody wants to be the person who takes the risk of going to trial," says Paul Murphy, an attorney who represented former coach Bill Fitch in his legal battles with the Clippers. "Everyone wants to get on with their lives." Except for the Smoking Gun and a blogger or two, the media have remained largely mum about Sterling too, apart from chronicling his dustups with Dunleavy. Most sports beat writers don't cover business issues, most business writers don't cover sports, and most columnists stopped taking Sterling and the Clippers seriously years ago. The NBA Players Association has no comment on Sterling as an owner or a landlord, or even about his relationship with Hall of Famer Baylor. As for prominent former Clippers, from Bill Walton and Danny Manning to Lamar Odom and Shaun Livingston, nearly all declined on-the-record comment for this story. In part, this is because players are trained never to forgo an earning opportunity, and where's the upside in poking the eye of an owner? But talk with enough athletes off the record, and you also get the sense that many pros feel they have more in common with team owners than tenants. At the very least, nobody likes having his business deals, or private life, scrutinized. TV analyst Mark Jackson (who provides commentary for ESPN) says he "never had a problem" with Sterling, either when he played for the Clippers from 1992 to 1994 or at any other point in his 18-year career. Then he adds: "I heard about the housing case -- what can I do about that? That's his business, and it's in the courts. A lot of players, owners, people at ESPN have been charged or sued over something." In May 2002, Sterling met with the staff of the newly acquired Wilshire Tower Apartments. He talked about his plans to make the 20-story building a beautiful landmark. Then, according to sworn testimony given in 2004 by building manager Dixie Martin, he said, "I like Korean tenants." Raymond Henson, head of security at the building, who was standing outside the room, heard what happened next. Sterling, according to Henson's 2004 sworn statement, once again expressed his distaste for Mexicans as tenants, saying, "I don't like Mexican men because they smoke, drink and just hang around the house." Later, Sterling told Martin that he knew he shouldn't discriminate. But he had the right to do so, she recalled him saying, because he owned the place. Prove him wrong, and you'll be the first.

|