|

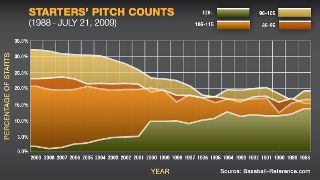

The names and teams aren't important, but here's what happened in July 2008 on a beautiful evening at Nationals Park. The visiting pitching coach went to the mound to talk to his pitcher, who was laboring slightly. "I can't pitch any more," the pitcher told the pitching coach. "Are you hurt?" the pitching coach asked. "No, I just can't pitch any more," the pitcher said. Then he walked off the mound. He had thrown 90 pitches. Welcome to the new age of baseball, an age in which complete games are rare, an era that has brought a new magic number of pitches by a starting pitcher: 100. At that point everyone worries about his either getting hurt or getting rocked. In 1988, 18.5 percent of all starts were in the 96-105 pitch range. In 2008, that number jumped to 32 percent. In 2000, there were 454 starts of at least 120 pitches. Last season, there were 71 starts, or 1.5 percent, an 84 percent drop. In 2009, 1.9 percent of starts have been 120 pitches. The drop from 120 to 100 can be traced to 2001, when the percentage of 120-pitch starts fell from 9.3 percent in 2000 to 4.8 percent. Why? What happened in those years? Since then, the decline has been steady. If a pitcher throws 120 pitches now, it is no longer considered normal; in fact, right or wrong, it is almost considered to be abusive. Here are eight possible explanations for stopping at 100. The offensive explosionThe past 15 years have represented perhaps the greatest offensive era in history. The reasons include smaller ballparks, a strike zone the size of a license plate, improved bat technology, steroids, weightlifting and harder baseballs. The 1999-2000 seasons were the apex of the offensive explosion: In 1999, more teams scored 20 runs in a game (nine) than in the decade of the 1960s combined (six). The game is different now than it was even 25 years ago. The Blue Jays' double-play combination, shortstop Marco Scutaro and second baseman Aaron Hill, has homered in the same game three times this season; it had never happened in the first 32 years of the franchise. So perhaps the explanation is as simple as this: Pitchers were hit so hard and so often in 2000, they were taken out of games long before they got to 120 pitches.  "Since 1968, I believe the intensity of every pitch has gotten harder and harder in the big leagues," said Orel Hershiser, the National League Cy Young Award winner in 1988. "In 1968, guys threw over the top, the ball went downhill and became a moving fastball. When they lowered the mound in 1969, they took away the pitcher's leverage. They took away the plane of the baseball, and a straight pitch became more on the plane of the bat. At that point, pitchers had to move the ball so it was not on the plane of the bat, and to do that, they had to increase the intensity on every pitch. Movement became a key, not just velocity. So with all the elements we have today, if the intensity of one pitch is increased by, say, 10 percent, then 125 pitches becomes 115, which becomes 110, then becomes 100."

"Since 1968, I believe the intensity of every pitch has gotten harder and harder in the big leagues," said Orel Hershiser, the National League Cy Young Award winner in 1988. "In 1968, guys threw over the top, the ball went downhill and became a moving fastball. When they lowered the mound in 1969, they took away the pitcher's leverage. They took away the plane of the baseball, and a straight pitch became more on the plane of the bat. At that point, pitchers had to move the ball so it was not on the plane of the bat, and to do that, they had to increase the intensity on every pitch. Movement became a key, not just velocity. So with all the elements we have today, if the intensity of one pitch is increased by, say, 10 percent, then 125 pitches becomes 115, which becomes 110, then becomes 100."

Hershiser said the strike zone "now is the smallest it has ever been. When we lost the height on the strike zone, we added some width, but then there was a trend to cut down on violence in sports -- in hockey, the third man in -- in the early 1980s, and with the new rules in baseball, we lost the inside corner. So you pitch in, hit a batter, and a fight starts." Hershiser made his major league debut in 1983. "I could rest at certain times during the game: two outs, no one on, seventh hitter up in the National League," he said. "I didn't want to show all my bullets at that time, so I'd throw a BP sinker away and get a ground out. If the guy got a hit, no big deal; you had the eighth and ninth hitters up. But you can't do that today with these lineups. You can't throw only 80 percent of what you have. You can't get by with a get-me-over curveball. What used to not be a big deal is now a huge deal." High-intensity pitches are often high-stress pitches. Teams all across the major leagues don't just count pitches; they count the number of pitches a pitcher makes under duress. "The philosophy in our organization is, 'How did you get there?"' said Red Sox pitcher Josh Beckett. "When we have a 25-to-35-pitch inning, that's highly stressful for a pitcher. Our guys are very conscious of that. When you're in a highly stressful situation -- runner at second base, none out -- one pitch becomes a pitch and a half. We pay attention to that." Specialization of relievers"That's the biggest change," said Padres manager Bud Black, who pitched in the big leagues from 1981 to '95. "We have 11-man, 12-man, 13-man pitching staffs today. We develop relievers in the minor leagues, college and even high school. It never used to be that way." In the 1970s, Orioles manager Earl Weaver often would break camp with eight pitchers. And back then, when the game's best pitchers threw 25 complete games in a season, Weaver would let ace Jim Palmer finish what he started, asking "Who do you want pitching the ninth inning with a one-run lead, Jim Palmer or the ninth-best pitcher on the team?" But now, the ninth-best pitcher on the team might come out of the bullpen throwing 95 mph. And the ninth-best pitcher on the team might be making a lot of money. "We've got two relievers on our team who are making $3.5 million a year, and they've never even seen the eighth or ninth inning," said one AL pitching coach. "When you're paying guys that much to pitch the sixth and seventh inning, you have to use them. We took our starter out after six innings the other day, and we lost. But when in doubt, teams take out the starter." Cardinals pitching coach Dave Duncan said, "Twenty years ago, did you ever hear a pitcher talking about his role? No. Now, everyone has to know his role, his specific role." Hershiser laughed, saying, "When I broke in, teams broke camp with eight or nine pitchers, nine to 10 at the most. Rookies prayed they'd keep 10 so they could make the team. Carrying 11 was unbelievable. It was like, 'What are you doing? Your bench is so short.' Now we've got 12 and 13 pitchers on the team! And we have a bunch of relievers who don't like to come into a game with runners on base. So we eliminate even more innings by a starting pitcher by allowing a reliever to start the inning with no one on base."  It's baseball's fault"We have conditioned our pitchers to go 100," Black said. "It didn't used to be that way. When I came up [1981], we pitched until we were ineffective. We would go 125, 130 pitches all the time. Now it's 100. We have pitch limits in Little League, in high school. We are so cautious of their talent, we are not encouraging them to go on. Today's athlete is bigger, stronger and faster than ever. They should be able to do more, but we don't let them." Johan Santana won his first Cy Young in 2004; his highest pitch count in any game that season was 116. Jake Peavy won the NL Cy Young in 2007 without completing a game. The three longest team streaks in baseball history without a shutout are by teams in this decade: 645 by the 2001-05 Rockies, 532 (active) by the Padres and 458 by the Nationals. Pitch counts have existed in the minor leagues for many years. As a minor league catcher in 1965, Duncan said he remembers one of his pitchers being taken out after 100 pitches even though he had a no-hitter going. But the rules on pitch counts today are much stricter. "In the minor league system, we limit our guys to 100 pitches," said Mariners manager Don Wakamatsu. "When they get to the big leagues, there are health and stress factors. College pitchers might throw 200 innings in a year. So we shut them down. We are trying to maximize innings and maximize starts. You're trying to get 33 starts from a guy. If you push a guy one time out, you might back him off the next. We're looking at total volume." We are now obsessed with pitch counts. "It's more mental than physical," said one NL manager. "I have pitchers who come up to me all the time when they come off the mound and ask, 'Is that it?' And I say, 'Yeah, that's it,' because I know they don't want to pitch anymore." There aren't many Josh Becketts in rotations these days. "My philosophy has always been I'm staying in the game until someone comes out and takes the ball, or the game is over," Beckett said. "That way, I'm not tempted to go out there thinking any other way." The quality startThe term has been a part of baseball for over 20 years, and is defined as any start that is at least six innings pitched and no more than three earned runs. We have a generation of pitchers thinking if they go six and keep their team in the game, then they've done their job. "That's the biggest thing to me," said Phillies manager Charlie Manuel. "Six innings, that's about 100 pitches. That's where the magic number came from, I think. When I managed in the minor leagues [in the 1970s], when we got a guy to 120 pitches, we would start to watch, but we'd go as high as 140 pitches. But every year since, [the number of pitches] keeps on dropping." The Rangers, under club president Nolan Ryan, have changed the definition of the quality start, making it seven innings and three runs, instead of six innings. It seems to be working. The Rangers are pitching better than they have in several years, in part because they're being pushed to go deeper into games. "Curt Schilling said it best: six innings and three runs is a 4.50 ERA," Beckett said. "That is not a quality start -- not from where I come from." Today's young general managerTwenty years ago, nearly 90 percent of all GMs had played in the major leagues. Now there are three out of 30: Philadelphia's Ruben Amaro Jr., the White Sox's Kenny Williams and Billy Beane of the A's. This decade has brought a new breed of GM, one who is highly educated, can run a spreadsheet and has mountains of data to support his theories. "We have a new wave of general managers who are deeply into mathematics, analysis, metrics -- I'm not saying it's wrong -- because that's what they charted in the minor leagues," said Rays pitching coach Jim Hickey. "I don't know the numbers, but the new wave of GMs are the ones who have charted that the chance of injury is, say, greater at 85 pitches than it is at 75. And with every five-pitch increment, there's a 22.8 percent more likely chance that someone gets hurt. With each 10 extra pitches, it goes up by five percent." The new GMs sometimes clash with the old-school manager about how the club should be run. Often, the GM wins. "My GM used to load reams and reams of paper on my desk about that night's game," one former manager said. "Sometimes I'd read it; sometimes I just throw it in the trash. But in the end, if it comes down to him or me, he's usually going to win. And if the discussion is about pitch counts, he is always going to win." We, the media"What year was it that Pedro Martinez was left in the game against the Yankees in the playoffs?" asked Wakamatsu, referring to the 2003 American League Championship Series when Red Sox manager Grady Little chose to leave Martinez in the game. Martinez lost the lead, the Yankees won in extra innings and knocked the Red Sox out of the playoffs, and Little was fired after the season essentially for leaving a starting pitcher in too long. "After that, the education of the public has changed so much. There was so much public scrutiny over that." Duncan agreed, saying, "If you're a die-hard supporter of a team, or someone who covers the team, what happens when the top pitcher on the team breaks? Everyone looks at the pitch count. The first thing they're going to do is see if there's any possible way that the pitcher was abused. The media is now setting the standards for how many pitches to throw." Hershiser said, "The advent of video, and timeline video, and games on TV, have changed a lot of things. There used to be two or three games a week on TV. Now every game is on TV. Scouting has changed completely, also. The mystery of pitching has gone away."  InjuriesMore pitchers are on the disabled list today than ever before. It's a paradox: The less they throw, the more often they get hurt. Long before 2000, there were cases in which pitchers perhaps threw too much and got hurt, including the young A's staff in the early 1980s (Mike Norris, Rick Langford, et al.), followed by the Mets' young trio of Paul Wilson, Bill Pulsipher and Jason Isringhausen. In 1998, sensational Cubs rookie Kerry Wood won 13 games and had a 20-strikeout game, but he broke down the following spring training and missed the 1999 season. That seemed to start making teams be even more cautious with young pitchers. "It's all about protection now," Beckett said. The Braves did a great job of protecting their pitchers, and winning games, in the 1990s and into this decade. Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine never went on the disabled list in the 1990s for Atlanta. Maddux had 14 120-plus pitch games with the Cubs in 1991-92. He had five with the Braves in 1993, only four the next two years and none by 1996. Surely other teams noticed the success and durability of the Braves' starters, and followed their lead.  Over the past 10 years, it has become even more important to protect a pitcher's health given the salary explosion that has left the average salary for a major leaguer over $3 million a year. Last year, the Brewers pushed CC Sabathia down the stretch, starting him three straight times on short rest.

Over the past 10 years, it has become even more important to protect a pitcher's health given the salary explosion that has left the average salary for a major leaguer over $3 million a year. Last year, the Brewers pushed CC Sabathia down the stretch, starting him three straight times on short rest.

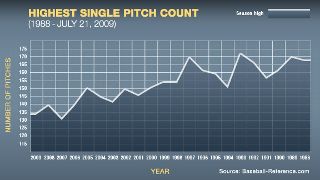

"The money has a lot to do with it," Hickey said. "Sabathia throwing that many pitches on short rest would have never happened if he was in the middle of a six-year contract. But he was allowed to do that because he was going to be a free agent." Hershiser said, "Pitch counts have crept into the heads of managers, pitching coaches and doctors in part because of CYA, cover your ass. When you take an MRI, the look after 50 pitches looks different than the look after 100, and people put numbers to them. No manager wants to lose his job because he got someone hurt. So he stays within the cutoff number." Duncan said he "doesn't give a damn about what people say about pitch counts because I know the individual pitcher. [Chris] Carpenter threw 114 pitches the other night. It was his first time over 110, but we're aware of his history with his surgeries. What we've done with him and Adam [Wainwright] is to take their bullpen sessions and warm-up sessions and cut them in half. Where they might have thrown 75 pitches before a game, now they throw 40. They're not wasting pitches. That's why we're not reluctant to go 120." On the final start of the 1989 season, Hershiser threw 11 innings and 169 pitches in a meaningless game, or so it seemed. He underwent arm surgery the next year, and missed almost all of the 1990 season. "I stayed in that whole game because I was one game under .500 coming in, and I didn't want to finish with a losing record," Hershiser said. "I told [Dodgers manager] Tommy [Lasorda], 'I'm not coming out of this game. I have to win.' I knew I was going to have to have surgery after the season. That game wasn't the reason." Still, teams noticed that he missed almost a full season after throwing 169 pitches in one game. So many young pitchers"I'd like to know the average age of the rotations in baseball before 2000," said Cardinals manager Tony La Russa. "It seems to me, back then, we had one guy in his 30s, a couple of guys in their prime at 29 to 31, and only one of the five in his early 20s. And those guys could all throw more than 100 pitches in a game. But now, it seems, we have three of the five in the rotation who are in their young 20s. [Former manager] Paul Richards once explained this to me, and it makes a ton of sense: As a young pitcher, the arm is growing. It is developing strength. It doesn't have the musculature that it's going to have in a few years. That's how you develop arm and elbow strains, even core injuries, because a young body isn't like a mature body, and it is just not as strong as it's going to be." La Russa added, "Young guys today rely on stuff. They throw 100 pitches; they don't pitch 100 pitches. They are max effort on every pitch. And in the minor leagues, they're doing whatever they can to get from Double-A to Triple-A, so the stress level is higher. They're getting to the big leagues younger, there is maximum pressure to perform, and because of that, they are letting it fly. That's how young pitchers develop arm injuries and fatigue. In the old days, pitchers spent time in D ball, C ball; they threw 500-600 innings, sometimes 700-800, on lower levels. There was no carrot out there like there is now to move up. Today's young pitchers are firing 85-90 pitches, fatigue sets in, and the next 15-20 they throw, they're still firing. A veteran at 70 pitches might have all kinds of stuff left. Clubs that have a lot of young pitchers are leery of pushing them because they know it's smart not to push them because they are throwing, not pitching." Hershiser said, "If your mechanics are good, you can throw 75 pitches without being taxed. But if your mechanics are not in order [as with some young pitchers], you could be worn out at 35 pitches. The light bulb goes on with a veteran pitcher about how to extend his career beyond injury and time by understanding the game. The biggest point of Greg Maddux's career came when he understood that softer was better, that throwing an 83 mph sinker was better than throwing an 88 mph sinker. As a pitching coach, I'd tell our guys that your best day is not your hardest day. That's a huge lesson to learn for young pitchers." It will take time for young pitchers to learn that. In the meantime, look for the magic number to stay at 100 for a while. But former Orioles pitching coach Mike Flanagan, who won the AL Cy Young in 1979, had an interesting idea on dealing with pitch counts. He had a pitcher who would ask him after virtually every inning, "How many pitches have I thrown?" Finally, Flanagan decided to count every pitch the pitcher threw that day, including every warm-up pitch in the bullpen before the game and every pitch between innings. After six innings, the pitcher came off the field and asked Flanagan, "What am I at?" Flanagan said, "250 pitches." The pitcher never asked again. Tim Kurkjian is a senior writer for ESPN The Magazine. His book "Is This a Great Game, or What?" was published by St. Martin's Press and became available in paperback in May 2008. Click here to order a copy.

|