|

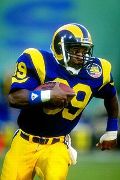

CAMARILLO, Calif. -- He's slumped behind a desk, looking frumpy in a sweater vest and tan cap. Tonight, he is living the life of an entrepreneur, pushing to get out the next issue of his glossy athletes-only magazine while he sneaks peeks at the financial news and stock charts on a bank of three super-sized computer screens behind him. The scrappy old center fielder, remembered as "Nails" by adoring Mets and Phillies fans, is chasing money, lots of it -- "cheddar," as it's called in his SoCal lingo. Without being asked, the self-styled investment master -- who, at this moment, is up to his thick neck in lawsuits -- volunteers that he's worth $60 million. This is how it goes for Lenny Dykstra. In case you missed the HBO profile last year or the magazine stories that trumpet Dykstra's business acumen, his life beyond baseball includes acquisitions such as hockey legend Wayne Gretzky's old house ("the best house in the world," Dykstra says) in Thousand Oaks, Calif., which he bought for $18.5 million. He drives a black Rolls Royce Phantom with an extended wheelbase, and hires pilots to fly him around in his Gulfstream II jet. His life in high finance includes street cred, too, at least for now. CNBC personality Jim "Mad Money" Cramer hypes him as a stock guru. On an investment Web site co-founded by Cramer, subscribers drop $999.95 a year to get Dykstra's options picks. "People invested with me made 250-large last year. That's $250,000," Dykstra says, which if true should earn him a front-row seat in the Obama cabinet. On this March evening, he talks up his purchase of a private jet earlier in the day, then eases off a tad. ("Just say we're getting close," he says.) He lets drop that he's chartering a jet to Cleveland later tonight to size up another Gulfstream. Then, it's off to Reynolds Plantation, an affluent golf community on the stretch of Georgia road between Atlanta and Augusta, to see if he can drum up some more business. And before all that, there's a "wealth party" to crash a mile or so from his corporate headquarters, which consists of four partially completed offices in a private jet hangar overlooking the runway at the Camarillo Airport. About his portfolio, Dykstra says: "They probably think I'm selling drugs. Got a house on the hill, couple planes. From what, hitting the ball where someone is not standing? What a wonderful world. But it's not coincidence. Like when I came to the Mets and took them to the World Series. I got to the Phillies, last-place team, and take them to the World Series."  The smack has just begun. Just ask about The Players Club, the year-old magazine started by Dykstra and geared to wealthy athletes. He ships 20,000 copies of each monthly issue free-of-charge to clubhouses and locker rooms, to agents and league offices. Along with stories profiling marquee athletes, its pages are filled with promotional displays for luxury rides, palatial digs ("trophy homes") and financial advice from Dykstra himself. In his grand scheme, Dykstra says, his parent company -- The Players Club Operations, LLC -- is about creating a lifestyle, making available to athletes a TPC credit card, a concierge service, a charter jet service and access to an annuity program to insure a recurring cash flow in retirement. "It's about living the dream, bro," he says. And after thumbing through a series of lawsuits that stretches from coast to coast and chatting up his business associates, you wonder if this aspiring financial Pied Piper is, indeed, living in a fantasyland. You wonder if the dream, built on glitz and greed in a time of economic uncertainty, is a teetering house of cards. You wonder if anyone this side of Bernie Madoff has ticked off more people -- business partners and family, alike -- than Lenny K. Dykstra. The lawsuits suggest that one of two things is going on here: Either Lenny hates to pay his bills, or he's a financial train wreck. Just in the past two years, Dykstra has been the subject of at least 24 legal actions, including 18 since November. Three suits hit the courts on Jan. 29. He's been sued by publishers and print companies, by three different groups of pilots and by a Maryland-based financial and litigation consulting firm that offered expert testimony on his behalf in an earlier lawsuit. He's even been sued by a die-hard Mets fan who was the best man at his wedding 20-some years ago, though that New York investor claims there is no bad blood. One of the angry souls is Dr. Festus Dada, a Nigerian-born gastric bypass specialist, who filed a fraud/breach of contract suit and alleges Dykstra kept a $500,000 deposit after a deal fell apart to purchase a Southern California car wash and retail center then owned by Dykstra. Dada walked away from the transaction, claiming in the suit that Dykstra had made significant changes to the final escrow agreement, including the insertion of a five-year contract for Dykstra's old Phillies teammate, Pete Incaviglia, to serve as general manager under the new ownership. "We had a closing date, but the good doctor thought there were no rules in this country," says Dykstra, pointing out that Dada himself has been a defendant in dozens of civil suits since 2000. "You'll see a laundry list [of suits], dude. OK, so much for Dr. Dada's credibility, huh?" Dada's side of the story, not surprisingly, is different. He suggests the ex-ballplayer set out to rip him off, saying he believes Dykstra was desperate for cash and rushed to close on the $27.5 million deal within 30 days. Dada's attorneys say the property was so encumbered by liens that it was impossible to close so quickly. "He thought he could keep my $500,000 and nobody would have the resources to go after him," Dada says. "But in this case, I am going after him. General surgeons are not intimidated by professional athletes. "Like I told him, if I can cut somebody from the neck all the way down to the pubis with a scalpel, then I cannot be intimidated." The claim by Dada, which with damages totals nearly $1 million, is just the tip of Dykstra's current legal and financial woes. Two Players Club vice presidents filed claims for unpaid wages after they quit in January. The Minneapolis-based firm hired to design his Players Club Web site alleges Dykstra stiffed it on a $1 million contract, and then bounced two separate $125,000 checks. In a particularly curious hunt for cash, Dykstra borrowed $250,000 from New York literary agent David Vigliano last May with an agreement to repay him $300,000 in November -- a robust 40 percent annual percentage rate. Vigliano filed suit after Dykstra didn't come up with the money. The high-powered global law firm K&L Gates, which waged many of the legal skirmishes on Dykstra's behalf, withdrew its representation late last year because it was "not paid current," according to his former lead counsel, David Schack. To which Dykstra says, "Four million I paid him. What do you mean, isn't that a lot to you?"  In an Oct. 10, 2008, legal filing, the firm wrote, "The client has refused to pay its legal fees, despite repeated requests." Schack refused to comment on the amount that Dykstra allegedly owes, or whether he has made any payments. The Gretzky estate that Dykstra bought for $18.5 million -- he planned to flip it for a sweet profit before the housing market belly flopped -- now sits vacant and is listed at $16.5 million. According to public records, four notes and deeds of trust are held against the property, totaling more than $13 million. One of the note holders, Index Investors LLC, filed a default notice in March, alleging Dykstra was behind on his payments in the amount of $422,436. An official with the Ventura County Tax Collector's Office told ESPN.com that, as of April 21, Dykstra owes nearly $400,000 in back taxes on the Gretzky house as well as his own longtime residence in the same gated luxury community. And his cherished toy, the Gulfstream jet? A Cleveland-based aircraft service company refused to release the jet and filed suit last month, alleging Dykstra had failed to pay more than $227,000 owed for cabin upgrades and repairs. On Feb. 20, three weeks before Constant Aviation filed the suit, Dykstra wrote in an e-mail to a company official, which it included in court filings: "I have busted my ass for the last 5 days working on the money -- please don't give up on me -- I WILL PAY YOU." On March 6, Daniel Noveck, an attorney representing Dykstra, pleaded in an e-mail for the company to release the aircraft, promising the debt would be covered after the sale of the Gretzky house, which he noted "is scheduled to be completed next week." Attorneys for Constant Aviation filed suit 10 days later. According to an online aviation tracking site, flightaware.com, the aircraft has remained in Cleveland since Feb. 12. Even members of Dykstra's family are lined up on the list of those to whom he owes money. His older brother, Brian, has yet to collect a $12,000 judgment awarded by the California Labor Relations Board. His younger brother, Kevin, alleges Dykstra cheated him out of $4 million on the sale of the family-run car washes, though Kevin hasn't filed suit. On April 16, Terri, Dykstra's wife of more than 20 years and the mother of their three boys, filed for divorce. Through her attorney, she declined to comment for this story. The family rift runs so deep that until recently, Dykstra had spoken to his mother only once in the past three years, according to his brothers, and wasn't allowing her any contact with his sons, her grand children. Last month, though, on March 23, Dykstra picked up the phone and woke up his mother with a call at around 6 in the morning, according to Kevin Dykstra, his younger brother. Lenny was stranded in Cleveland. He wanted to charter a jet so he could get to a business meeting on the West Coast, and his credit cards were maxed out. He needed nearly $23,000 and asked his mother for it, Kevin says. His mother agreed to let him use her credit card. Kevin Dykstra says she has yet to be repaid. "He had no money," says Lenny's brother. "He is on the phone, crying to my mom, saying he has got to get home and he is in Cleveland, Ohio. He asked my mom to put up her credit card for 23 grand. That is just sick, dude. "The whole family is mad and she is all sad, saying he caught her off guard. She was asleep. He was crying to her, man." About the use of his mother's credit card, Dykstra says, "Listen to me, the millions of dollars I've spent on them -- I mean, I don't know what you're talking about. That is why I can't talk to you no more." Dykstra met twice in person with a reporter for this story in early March, and spoke as well in several phone interviews; but over the past month, he repeatedly declined interview requests to discuss new allegations raised by family members and former employees until that quick comment on April 17.  Going for brokeLenny Dykstra, the ballplayer, was a cocky, high-charging risk-taker known for barreling into second base or launching himself in daredevil pursuit of a line drive into the gap. He never seemed to be without his swagger, even when then-commissioner Fay Vincent put him on probation in March 1991 after Dykstra admitted to losing $78,000 in high-stakes poker games, or two months later when he crashed his red Mercedes sports car the night of a bachelor party for one of his Phillies teammates. Maybe his current pursuits are variations on those same flights of chance. The Gretzky house. The magazine launch. The grand investment plans designed for pro athletes. The deep-in-the-money option calls. The private jets. But, after all these years, has his luck run dry? Is he broke? Is The Players Club already on its last leg, eight issues into its existence? "No, dude, the f---ers want more money," Dykstra says about the lawsuits and the debts. "Dykstra has all the money." He pauses. Then says, "At the end of the day, it is all about the book, The Players Club. [It's] just the beginning of something that'll be around locker rooms forever. Only thing that matters is that the book gets in the players' hands every month. You got 10 pages [of financial advice, including Dykstra's column] every month to help the players." Asked how many people he employs, Dykstra says 12,000 -- a reference to the pro jocks who presumably get access to his magazine in their locker rooms and clubhouses each month. Dykstra boasts that he's sinking $500,000 a month into the magazine, which, he claims, has yet to sell ads, though former employees say a few of the spots have been sold or bartered. He turns to a computer screen and pulls up what he says is the next cover, featuring young hockey stud Sidney Crosby under a headline that reads "Lord of the Rink." He recently moved the magazine's headquarters from New York -- where he left a trail of ill will as well as unpaid bills with a national outfit that rents temporary office space -- to modest digs on the second floor of a private jet hangar about 50 miles northwest of Los Angeles. His 20-by-20 wood-paneled office is adorned with framed magazine covers, an array of baseball memorabilia and a heavy, sculpted bronze eagle that sits atop a cabinet behind his desk. The eagle is inscribed: To Lenny and Terri

Thanks for all your help and support

Your friend

George W. Bush

December 2004 "I don't talk politics," he says when asked about the gift. His business plan is another story. He talks plenty about that during the early interviews for this story. Asked if the ambitious design to provide a handful of specialty services for pro athletes is in place, Dykstra says confidently, "Have I got a 12-inch c---, or what? Of course, it is all in place. It might not look like it, but everything I do is part of a plan." He sounds convincing. But Dykstra can't seem to put his hands on anything resembling a tangible product other than the magazine, which he gives away free without a subscription. His proposed annuity vehicle for athletes remains grounded after he didn't close a management deal with AIG on the eve of the insurance and financial giant's $170 billion (and counting) taxpayer bailout that kept it afloat last fall. And the credit card and concierge service for high-rolling athletes appear to be languishing in the "vision" stage. A number of people who have worked for him -- and employees seem to have come and gone at a breakneck pace over the past year -- claim the business runs on Dykstra's whim and little else. "It was a sham," says Mike Hobbs, who was hired as executive vice president of The Players Club Operations in December but left 45 days later. "There was no business plan. No infrastructure. It's a wonderful idea, but The Players Club is a fantasy." Dykstra apparently hasn't handled any player investments yet, and it's difficult to determine whether any athletes seriously consider his financial advice, either in the magazine or through his subscription financial service. The early plan was for an athlete to invest at least $250,000 with professional money managers of Dykstra's choosing. Former employees say Dykstra made the rounds in New York trying to line up a financial partner, but the closest he came was with AIG, now a corporate poster child for outrageous greed. An AIG executive and Dykstra offer conflicting opinions on who backed away from the deal. AIG spokesman Charles Armstrong says it was the company's decision not to go forward. But Dykstra produces a copy of a Dec. 10, 2007, letter from an AIG vice president reaffirming the company's interest in being an "exclusive strategic partner." An accompanying commission schedule proposed to pay The Players Club $90,000 per player recruited to both the AIG universal life insurance and income annuity programs in the first year. There was a caveat, though: Dykstra had to bring in at least 100 athletes. "I said, 'No,'" Dykstra says with a grin. Then, addressing an ESPN.com reporter, he adds, "Hey, I don't hear, 'Good job. What a good decision, Lenny.'" Before the deal fizzled, Dykstra acted as if he planned to do business with AIG. In the 2008 preview issue of The Players Club, he wrote: "This column is not going to be a place to get stock tips. It will offer financial information from AIG that will show players how to build wealth, plan for the future and protect their families." Four pages of AIG promotional copy followed. The next issue, the magazine's debut last April with Derek Jeter on the cover, carried seven pages of copy touting AIG, including an AIG number to call. In subsequent issues, the AIG pitch went away, but the magazine listed phone numbers supposedly directing athletes to others for investment and annuity advice. Two of those advisers were Paul Hollins, the brother of former Phillies teammate and close friend Dave Hollins, and a young financial services professional on the Players Club staff. Paul Hollins, a licensed broker with Wachovia Securities in Buffalo, N.Y., told ESPN.com that he received a number of calls from former players after the AIG display appeared, but none of the calls resulted in purchases or investments. Dykstra referred to Paul Hollins as "my broker" in a 2006 online column. In another issue, Dykstra listed a magazine phone number and wrote in his "Game of Life" article: "Call us and we'll help you find the financial institution that fits your needs and guarantees your long-term security." Today, that number rings to a voice mailbox for Dykstra himself. The early AIG mention caught the eye of at least one pro athlete, tight end Anthony Becht, the New York Jets' first-round draft pick out of West Virginia. Becht, who last month signed a free-agent deal with the Arizona Cardinals, followed up with a phone call to AIG but didn't invest. "I didn't speak to Lenny. I spoke to some general employee of AIG about annuities," Becht recalls. "Obviously, in the first couple issues [of the magazine], he was mentioning annuities and recommending AIG to call, saying they were the best in the business and this and that. I know there were some guys when I was with the [St. Louis] Rams that called -- even some guys that weren't making much money, younger guys just trying to get knowledge about different investments. I don't think they got involved. "In retrospect, I'm glad I didn't get involved. It was a little scary."  In the clubhouseSpending time in Dykstra's world is a trip. He shows flashes of brilliance, and can be funny and charming. Then, in the seconds it used to take him to bust down the first-base line, his behavior can morph into something altogether different. His associates say he goes without sleep for long stretches of time; and during a visit from a reporter, he briefly nods off at the computer in the middle of a late-night conversation. His hands tremble and his speech can be slurred, perhaps depending on the lateness of the hour. On this day in early March, Dykstra is in Los Angeles shuffling between business meetings. He sets up dinner with a reporter at Mastro's Steakhouse, his favorite eatery in Beverly Hills, but he cancels just before 8 p.m. He calls back two hours later and suggests meeting at his house, a two-story residence appraised at $4 million in the Lake Sherwood Estates County Club -- below Gretzky's old house on the hill in Thousands Oaks. Dykstra has since moved out of the house, according to family members. His ground rules are explicit: no discussion of "drugs or p----," the latter a reference to the female anatomy. He explains, "I'm 46 years old and don't want to deal with all that." The Rolls sits in the driveway. The walls of his office, at the far end of the house, are paneled in dark wood. Three laptops are fired up on his desk, and two more are idle on the floor. The TV is tuned to CNBC and Jim Cramer, his early patron. Dykstra still lives in a world of juvenile clubhouse humor and politically incorrect comments. In a recent "GQ" story, he was quoted referring to several African-American athletes who have appeared on his magazine cover as "spearchuckers." That comment raised the ire of an Atlanta Hawks official, who vowed to ban The Players Club from the team's locker room. Dykstra later denied making the comment. At his house on this March evening, he says this, unsolicited, about a CNBC guest: "They put a suit on that f--," questioning the guest's sexual orientation. When race car driver Danica Patrick appears on a TV commercial, he pipes up, "I made her, man. Put her on the cover [of The Players Club] and made her."  Ever the good host, Dykstra wants to show off "The Gretzky House." So at around 1 in the morning, he slides behind the wheel of his Rolls Royce and, while the reporter tries to keep up in a rental car, leads a race up the mile or so of dark, winding road. Dykstra's heavy foot makes a joke of the 25 mph speed limit in the neighborhood. "Dude, lost you, huh?" he says when the house has been located. No. Just didn't want to upset the neighbors, he is told. "Doesn't matter," he says. "I don't know any of them, anyway." With that, Dykstra shuffles up to the front door, which opens into a magnificent neo-Georgian estate that resembles Thomas Jefferson's Monticello. Suddenly, all hell breaks loose. The security alarm goes off, blaring through every room in the vacant mansion and into the otherwise calm night. Dykstra fumbles comically with security boxes over much of the next 30 minutes, unable to bring silence. Yet no security company or cops show up. The place, as might be expected, is something out of "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous." It's not so much a house as a compound spread over almost seven acres, with a pool house, a gym, a separate guest house and staff quarters. At one point, Dykstra listed it for $24.9 million, though he's asking $16.5 million now and talking about divvying it up 10 ways and selling it as a fractional house. In a second-floor hallway leading to what used to be Gretzky and wife Janet Jones Gretzky's bedroom, Dykstra spots a bat -- the flying variety -- balled up in a corner where the high ceiling meets the wall. He ducks beneath it with his hands clasped on his head, playfully screeching. Dykstra aims to impress and wants to hear that people are, whether it's by this opulent jock house, his magazine or his stock market advice. Outside, early in the morning, he flips on high-powered lights to show off the tennis court. "That's a killer, dude," he gushes. Yes, is the answer. It's nice. "What do you mean, nice!?" he says. "[Pete] Sampras comes over and plays on my court."  The wealth clubThe plan is to meet again the next morning at 11, back at his office in the jet hangar. But Dykstra spends the day somewhere else, purportedly talking with investors, working the phone. Finally, after 6 p.m., he wanders into the hangar, trailed by a driver and a couple of assistants. He's making arrangements to leave for Cleveland in a few hours. He's scarfing down slices of pizza and chasing them with root beer while he looks over pages for the magazine's upcoming issue. Amid the chaos, he's chatting up Ron Brown, an ex-football player, on his cell. Like Dykstra, Brown is a jock-turned-entrepreneur with a visionary sense and an eye for big money. Brown, 48, played eight seasons in L.A. with the Rams and then the Raiders, tasting modest success in the NFL after he won a gold medal in the 4x100 relay at the 1984 L.A. Olympic Summer Games. And like Dykstra, Brown has found success in the business world to be elusive. Public records reveal that he has been subject to at least a dozen judgments in the past 15 years -- highlighted by state and federal tax liens -- and that he filed for federal bankruptcy a decade ago, claiming $1.5 million in debt. "I always take partners, man," Dykstra, now pacing around his office, tells Brown over the phone. "You got to come over and see our place, man. You got to bring some guys, bro." Dykstra is pitching his magazine and his charter jet service, Legends Air. He likes Ron Brown a lot. When he gets off the phone with him, he's as pumped as a kid in a candy store.  "Ron Brown is running with some big cats, some big sticks," he says. "He's in some 'wealth club,' man. All rich f-----' people. I like the way he's moving and shaking." Later, Brown, who describes himself as a facilitator hired by a group of L.A. lawyers to "kind of bird-dog deals," returns the compliment. He appreciates Dykstra's business instincts. He likes the magazine. He likes his idea of setting up a structure in which athletes can network. He likes the success story, retelling how Dykstra got his financial act in gear after the 2002 economic downturn had sucked his $2 million mutual fund portfolio down to a measly $400,000. "I like the fact that he wants to use the magazine as a way to help players," Brown says. "He is trying to put together an entrepreneur concierge piece that will allow athletes to get involved with the concierge part, as far as having resort homes, access to so many hours on the jet and limousine service. He and I talked about that two years ago, about being able to have one location where guys can come to and get discounts and get legal representation and that kind of stuff." On this night, though, it is Brown who has the goods that Dykstra craves -- the company of rich suits in the wealth club. Brown is less than a mile away in Camarillo, across the Ventura Freeway, at the house of a friend who is hosting a club party where he can rub elbows with upward of 40 serious investors. They're all worth $50 million to $100 million, both Dykstra and Brown claim. So Dykstra, an assistant and a driver dash out of his office en route to the meeting, carrying plastic-wrapped bundles of The Players Club magazine. Inside the office elevator, Dykstra lifts his right leg like a dog relieving itself -- he retains a degree of the old flexibility -- and farts. Turns out, he'd forgotten more than his manners. He remembers that he left a cashmere sweater behind, too, which brings the elevator to a halt and sends Dykstra back to the office on a flight of retrieval. "I'm gonna get them with my cashmere, bro," he says, back in the elevator with the sweater. "Gotta go try and make some money." Later this night, as he has a few other times, Brown watches Dykstra perform his meet-and-greet with investors at the party. "You know, Lenny is a sharp guy," Brown says. "He has history, so guys like to hear some of his war stories and kind of understand his journey in life. Who Lenny Dykstra is today.

Why did he buy Wayne's [Gretzky] house? The kind of investments he is doing. How the stock [market] is treating him. How is the magazine? What are the numbers?"  Legal skirmishesWhat the wealth club moguls won't hear is the drama surrounding last November's issue of The Players Club. They won't see the photo of a toothy Cole Hamels, World Series MVP, on the cover, and with good reason. The issue, all 20,000 copies of it, is collecting dust in a Las Vegas warehouse. When Dykstra didn't come up with nearly $300,000 he owed for the previous two issues, Creel Printing and Publishing refused to distribute the November magazine. Now, Creel, a large, family-owned publishing company that printed and distributed five earlier issues of The Players Club, is on the list of entities suing Dykstra in some fashion related to his magazine. As other creditors have done, the claim here is that Dykstra talked a good game but was cash-short in the end. "A very, very strange guy," says Allen Creel, the publishing company's CEO. "I've been in business almost 60 years and I have never met anybody like this. All I know is he flies around in a big jet. He'll tell you, 'I'll meet you in California, in Del Mar.' You wait two hours for him to show up and he comes up in a big limo. He has his computer and all of his stuff. It's like a big fraud, big show. When we met him in L.A., we met him at the Beverly Hills Hotel and he acted like

he told me he lived there. And he said, 'This is my home away from home.' "He wanted to meet us about credit. He said he was in some kind of an insurance deal with these baseball players. He said the insurance company would be paying for the [magazine]. I said, 'I couldn't do that because our credit line is with you and you are the one that signed the personal guarantee.' And then, he said, 'Well, we'll work it out' and this and that. He tells me he has this house he bought from [Wayne] Gretzky and he's going to make $2 million or $3 million from it and he's got an offer on it. He's going to pay us as soon as it comes in. And then he started telling me he'd like to know if we could work a deal where we could fly his [private] plane and take that off the printing bill. I'm not the kind of guy that flies all over the world in a private jet. We're basically a family-owned business. We're not jet set." When the subject of the Creel lawsuit is raised, Dykstra counters that he's the victim in this business deal gone bad, and alleges that Creel overcharged on the cost to distribute his magazine to athletes. "One of the things I don't let people do is suck me out of my money," he says, agitatedly. "They think they can take advantage of athletes, dude.

I rip their heart out." Less than a month after The Players Club launched in April 2008, Dykstra found himself in a legal skirmish with the magazine's first publisher, the now-defunct Doubledown Media. A confidential settlement was reached after it was alleged that Dykstra had failed to pay $787,000 in expenses. Later, managerial consultant Joanne Katsch filed a $630,000 lawsuit for breach of contract alleging her CSJ Consulting firm hadn't been paid.  In the CSJ deal, Dykstra put up as collateral the Gretzky house and $23 million in promissory notes secured in 2007 as part of his sale of two Southern California car washes. According to court documents, Dykstra pledged the $23 million notes or took loans against them in at least four other instances, though they eventually were retired on Sept. 26. Jeffrey Gubernick, attorney for the businessmen who originally bought the car wash facilities, contends Dykstra came back desperate for cash a year after the sale and agreed to retire the notes in return for a financial bailout. The businessmen, most of whom are from Iran but now live in California, agreed to pay nearly $13 million in debt, forgave $1 million Dykstra owed them, and also gave Dykstra $1.25 million in cash, Gubernick says. Dykstra filed suit in February, however, alleging the businessmen haven't covered almost $1 million of his debt. "From our standpoint, that note is gone," Gubernick says. But that's news to William [Billy] Jurewicz, founder of Space 150, a digital media company hired by Dykstra in May to build out The Players Club Web site. The deal with Space 150 was for $1 million. As proof he could cover the bill, Dykstra again put up the Gretzky house and the same $23 million notes. The Minneapolis-based Web designers haven't been paid, even with the $23 million notes presumably retired in September. Instead, Jurewicz pulled his crew off the project shortly after Dykstra bounced separate $125,000 checks -- the first written on a closed account -- on Aug. 11 and Sept. 12. Earlier -- as Creel, the Vegas printer, did -- the Web designer heard Dykstra's pitch about free flights, and was further propositioned to partner up in Dykstra's charter jet service. "He was always spinning something really obscure," Jurewicz says. "And you know how Lenny talks. 'Hey, bro, got this deal, man. I got to get you into a bird, man.' And you're like, 'Listen, chief, I want a check.' "He thinks he's a celebrity and doesn't have to pay for much. And people donate or else he can clip it." Dykstra's response: Someone is screwing him again. "I told him, 'When the [Gretzky] house sells, you'll get your money,'" Dykstra says. "But I said, 'You got to build out the Web site,' 'cause no one in their right mind would pay $1 million. You might go to jail for that. That's like Jesse James. I mean, $1 million? A Web site?" This is the same Lenny Dykstra who, in hyping his grand design last year, told The New Yorker, "To do a decent Web site, you need two million dollars."  Flying colorsOne thing Dykstra particularly hates paying for is jet fuel. That's tricky because without it, his Gulfstream twin-engine "bird" will stay grounded and his vision of a charter service would be nothing more than a fanciful pipe dream. Even so, Dykstra fires pilots like George Steinbrenner used to fire Yankees managers. In some cases, he fires them on the spot after they refuse to pick up a refueling tab. In other cases, they simply leave in disgust, unpaid. At least six pilots are party to three separate suits brought against Dykstra since January. Thanksgiving weekend, pilot Sam Estrada was in Connecticut with his family and about to relocate to California when he says Dykstra called from Cleveland to say his credit cards were tapped out. Dykstra asked him to put a $7,000 refueling cost on his credit card. "I said, 'Listen, I don't know what you are going to do, but I don't have the money,'" Estrada says. "At that point, he says, 'You might as well stay home. You're fired.'" A month later, Estrada picked up the phone and heard Dykstra's voice again. This time, he was hot to check out a Gulfstream 550 up for auction. He wanted Estrada to fly him to Nice, France. "I said, 'You're crazy, man,'" says Estrada, who filed a wrongful termination suit in January. "It was ugly. I will never deal with any athletes again." Pascal Jouvence claims he parted company with Dykstra's operation minutes before he and Dykstra were to take off from Camarillo Airport for the East Coast. "He wanted me to use my own credit card to put fuel in his aircraft," says Jouvence, who filed suit seeking $5,000 in back wages. "When I refused, he fired me on the spot." Shortly after, Dykstra rehired a four-man crew that had previously quit over unpaid wages. To entice the pilots back, he signed an agreement Dec. 29 promising to pay the nearly $60,000 he owed them within two months, adding this handwritten notation at the bottom of the page: "But I will pay if [Gretzky] house sells -- immediately." Dykstra didn't pay again, and is accused in a lawsuit of breaking the agreement with two of the crew -- Mark Malone and his son, Miles -- to serve as his pilot and co-pilot.  Asked about that lawsuit, Dykstra says, "The father and son? You mean the ones that stole my log books out of my hangar? The bottom line is there is a reason for everything, dude." But according to his then-driver, Paul Lee, Dykstra was so angry at Mark Malone that he suggested Lee should rough him up. "He told me, 'You need to shut Malone up,'" recalls Lee, who played middle linebacker at Long Beach State in the late 1970s. "He goes, 'He needs to go to jail.' He said that a couple times. I said, 'Do you want me to call the police?' He goes, 'No, don't call the police. You need to shut him up. The guy needs to get hurt.'" Malone says Lee told him about Dykstra's instructions when the driver came by Malone's house to retrieve the flight logs. "I said, 'Paul, if you need to take a swing to save your job, that is OK,'" Malone says. "He goes, 'No, I'm not gonna do that.' Paul knew if he followed instructions, he'd go to jail, not Lenny.'' At about the same time, Lee says Dykstra was driving a Maybach, a German luxury car that sells for about $400,000. Lee claims Dykstra broached the idea of dropping off the Maybach at what he described as a chop shop run by the Russian mafia in L.A. Lee says Dykstra was behind on payments and suggested the car could bring a quick $150,000 -- $100,000 of it would go to Dykstra, $50,000 would be for his driver. "He gave me a name, but I don't remember it right off the top," Lee says. "He said, 'Get in touch with this guy.' I think one time he wrote down a number, but I didn't take it. I was, 'Wow, is this really happening?' He was dead serious. You know a person is serious when they mention it four times. He said, 'They'll chop it up, break it down into pieces and they'll send it overseas. And they'll reassemble it overseas.' "One time, he got back [from a business trip] and he said, 'Man, I thought I told you to get rid of this car.'" Lee didn't act on either suggestion -- Malone or the Maybach. After he quit in January, Lee filed a claim against Dykstra seeking $7,500 in unpaid wages. These, too, are among the newer allegations to which Dykstra has not made himself available for comment. Street credibility gapIn 2005, long before the drama and the lawsuits, CNBC's Jim Cramer, host of "Mad Money," gave the budding stock-picking wizard a "Nails on the Numbers" column on Cramer's financial Web site, TheStreet.com. Cramer has his own Philly roots -- he worked as a vendor in the early '70s at Veterans Stadium, where the Phillies played. He liked Dykstra's celebrity and his options tips -- which by Dykstra's estimate generated $3 million in subscriber fees last year for TheStreet.com -- so much that he promoted him as "one of the great ones in this business." Cramer has had his own problems recently, including a much-publicized debate with late-night comedian Jon Stewart over some of Cramer's market calls over the past years. Perhaps understandably, he wasn't interested in embroiling himself in the state of Dykstra's affairs right now. "I think I'm going to take a break from the old interview game for a while," Cramer e-mailed in response to an ESPN.com request for comment. "It hasn't been all that productive for me of late." In a follow-up request, Cramer wrote this about Dykstra: "His option picks have been very good. But he works for thestreet.com and reports to Dave Morrow, editor in chief. That's my relationship. That is my answer. There is no reason to comment further. And I thank you for your time."  Four telephone messages left for Morrow went unanswered. Dykstra's own analysis of his success in the market goes Cramer one better than "very good." "You know about my stock picking, dude?" he asks. "I'm 92-0 [last year], worst market in history. Three thousand people signed up and pay $1,000

I'm making people fortunes. I'm moving $3-5 billion a month." Some who track the market are skeptical he could be that successful. Options trader and author Adam Warner, for example, suggests that Dykstra isn't accurately accounting for losses. Warner says a Dykstra-recommended position lost more than $200,000 in January. "It is all nonsense," says Warner, options editor for the financial Web site Minyanville.com. "He'll buy a 10 lot of, say, IBM. And if it makes a dollar, he'll sell it. If it loses, he'll buy more and he'll keep buying more and more. So he'll never actually realize a loss. And he buys options that expire in as few as six months and sometimes as long as a year. He'll book his wins and he'll just let the losses run. So what happens is, he wins all his picks, but the losers may eat up 100 wins. The bottom line is how much money you make. It's not how many picks you make or what your winning percentage is." Last year, a Forbes Magazine article questioned whether Dykstra has always been the brains behind his selections. It suggested that Dykstra borrowed picks from one of his former mentors, market strategist Richard Suttmeier, who at the time offered his own selections via a subscription newsletter. The article revealed that among Dykstra's 17 buys last April, 11 had appeared days earlier in Suttmeier's newsletter. "Suttmeier is a good guy," Dykstra says when his name is brought up. Yet Suttmeier hasn't spoken to Dykstra since the Forbes article appeared, which coincided with the New York launch party for The Players Club magazine. The Forbes story factors into that silence, but Suttmeier also told ESPN.com that Dykstra owes $6,000 to his 35-year-old son. Jason Suttmeier was being paid $2,000 a month to provide Dykstra with stock-related spreadsheets, but Suttmeier's father says Dykstra had fallen three months behind in those payments. That's a service that Dykstra describes this way: "The kid hit 'go,' hit 'print' on the machine." "I taught him how to pick stocks," Richard Suttmeier says about Dykstra. "I told him what moving averages to use. Jason, my son, created the spreadsheets to track them every day. He sent them to me. I would look at them and then I would send them on to Lenny. And then he would have a subscription to my newsletter and that is what the Forbes article picked up. They tracked his picks versus mine, and made the claim he was getting the picks from me. But he was getting the picks from my newsletter that picks stocks, just like any other subscriber would. And Lenny also subscribed to about every newsletter known to man. "It just happened during a streak that Forbes covered he liked my picks better than others." He laughs, then says he appreciates the compliment in Dykstra's attention to his newsletter. But

"I don't want to be associated with anything that he is doing right now," says Suttmeier, chief market strategist for ValuEngine.com and an occasional guest on financial TV shows. "When he doesn't pay my son the six grand that he owes, I give up on him. It's simple. I don't do lawsuits or anything like that, but I don't want to be tied to him in any way moving forward. It doesn't make sense to me." Family dysfunctionsDykstra, by all accounts, is extremely close to his three sons, two of whom are grown and out of the house. Nineteen-year-old Cutter, his middle son, has been described by scouts as another high-energy ballplayer in the 'Nails' mold. Cutter, who signed with the Milwaukee Brewers last June after they drafted him in the second round, is playing for the Wisconsin Timber Rattlers in the Class A Midwest League this season. But Lenny has spoken to his mother only twice in the past three years, and he isn't on speaking terms with either of his two brothers. Ditto his uncle and some of his cousins. As family feuds go, this is a bloodbath, fueled by the money, greed and lawsuits that undid the comfort zone Dykstra established when he made his living as a pro ballplayer. Coming off the '93 World Series, in which he hit .348 with four home runs and eight RBIs in the Phillies' six-game loss to the Toronto Blue Jays, Dykstra started a successful chain of car washes and quick-lube establishments in Southern California. A number of family members were paid well for their help in maintaining it, including younger brother Kevin, who helped manage the business. But in 2006, a decade out of baseball and overseeing the business, Lenny sold the first of three car washes for $11 million; two others sold later for $40 million. Kevin insisted he had a verbal agreement with his older brother that entitled him to 10 percent of the business. When Kevin asked for his money, he says Lenny refused, and then fired him. "Lenny says everybody steals from him," says Kevin, a former minor league umpire. "And the truth is Lenny is the actual fraud, because Lenny doesn't like paying people he owes money to. When I called for my money, he says, 'I don't owe you anything. I never promised you anything. All you do is steal from me.'" According to Kevin, their mother, Marilyn, was upset that he'd been fired, and confronted Lenny at his home that day. When contacted for this story, she declined to revisit the family squabble, saying only, "It's just made me a very unhealthy person, in the hospital all the time [with] the stress over the whole thing."  Two weeks after he fired his brother, Lenny Dykstra fired his mother's brother, Wayne Neilsen, who'd left his job with Goodyear Tire nine years earlier to join the Dykstra family business. "It was a family deal," Neilsen says. "His mom knows. If he ever sold one of the car washes, Kevin would get 10 percent of the profit. "So he came up to me and said I had to make a decision. He wanted to know if I'm going to be on Kevin's side or his side. I said, 'There are no sides, dude. It is family.' He sent some hack [lawyer] up there and fired me." Even before the split, the brother and uncle claim Dykstra verbally abused them and threatened them with the loss of their jobs in a string of crude, vulgar e-mails. In a copy of one, provided to ESPN.com by Kevin Dykstra, Lenny Dykstra pleaded with his brother to have his "police friends" pay a visit to two former employees with whom he was in a dispute. The concluding line came with the directive: "DELETE THIS EMAIL IMMEDIATELY AFTER READING FROM ALL YOUR EMAIL BOXES – TRASH, SEND, ETC." When his brother is mentioned, Lenny Dykstra says, "Now you're getting into the real criminals. I bought him a brand-new house, this $1 million house, and paid him $500,000 a year. And caught him stealing and forgave him. And let him come back to work and [he] kept robbing me. Is that the brother? The one I had a restraining order against? Or is it the one that went to Vegas 90 times and used my credit card without me knowing, paid the minimum and then a $200,000 bill shows up?" Kevin Dykstra says Lenny filed the restraining order after Kevin had e-mailed some unsavory information about him to Terri, Lenny's wife, and that the order eventually was tossed out of court. Kevin dismisses the other claims, noting he has mortgage documentation on the house that proves he paid $512,000 for it in 2000, as well as tax returns to document his pay. "Because we worked for him, he tells everybody he bought my house, [and] my other brother's house," Kevin says. "That's how sick he is." Kevin Dykstra acknowledges that he briefed investigators for the Mitchell report as well as Major League Baseball security on what he describes as Lenny's use of recreational and performance-enhancing drugs during his playing days. Kevin says he was a source of the drugs for his brother, even after Lenny's baseball career ended. He also alleges that Lenny pressured him and others to lie during a 2004-05 arbitration hearing in which Dykstra successfully fended off a claim by his former business partner, Lindsay Jones, that he was entitled to a 25 percent stake in the lucrative car-wash business. Dykstra's attorneys portrayed Jones as having raided cash registers and demanded kickbacks from contractors. But as a result of Kevin, his uncle and two other former employees signing declarations that they perjured themselves during the arbitration, Jones' attorney filed a new lawsuit against Lenny Dykstra on Jan. 29. "Lenny was, 'You're my brother. If you don't lie and do this and do that, you're not going to have your job,'" Kevin Dykstra says. "And here I am making a nice quarter-million a year. My wife doesn't work. I got three children. So Lenny controlled me by the money. What am I going to do, just quit and go somewhere else? I can't." Lenny Dykstra didn't respond to subsequent interview requests about his brother's allegations. These days, the extended family keeps tabs on Lenny via court filings and stories in the media about the latest lawsuits. As a ballplayer, he lifted their spirits and made them proud, but they worry now that he might be sullying the Dykstra name. They worry, too, about what the stress of his business and his lifestyle is doing to his health. "It is sad what has become of Lenny," says his older brother, Brian, who is yet to collect on the labor board ruling that his little brother owes him $12,000 in unpaid vacation time. "My young son still loves his Uncle Lenny, though he never gets to see him. People ask all the time about Lenny. I tell my son, 'You tell them, Nails is your uncle and you're Little Nails.' We stay positive with that. Lately, we want to tell [people] he's a son of a bitch, that bastard. We're mad at him. "I think he should get on his knees and pray every night for the next couple months [that] things will start changing." Mike Fish is an investigative reporter for ESPN.com. He can be reached at michaeljfish@gmail.com.

|