BRADENTON, Fla. -- For a month now, baseball's shiny new pace-of-game speed-up lab has been spewing smoke out of Rob Manfred's test tubes.

Countdown timers tick. Hitters keep half a toe in the batter's box. Umpires point fingers. Between-innings promotions are cut off in mid-schtick.

And a month into this fascinating experiment, here's what we're wondering: Will anybody really notice?

From his primo seat in row two, Infield Section 8, at storied McKechnie Field, spectator Tom Rogers actually asks this question himself -- and then tells us exactly what sort of dish he thinks baseball has ordered up on its pace-of-game grill:

"It's a nothing-burger so far," he says, unequivocally. "It absolutely has not changed the pace of anything."

Rogers has been attending two or three games a week since the start of spring training, just being a fan. He spent two decades before that working as a scout for the Pirates and Mets. And now, after staring intently at those newfangled between-innings countdown timers for weeks, he's having a tough time telling the difference between the games he used to watch and the games he's watching now.

"Just about every game we've seen so far this spring, it's been a three-hour game, or more," he says. "We've had one 3½-hour game. Probably, if you look at it at the end of the year, it might take a minute or two off the average time, and it would be a big victory for the new commissioner. And anything helps. But I really haven't seen any difference. And I've been watching the clocks since they first went up. Just for the heck of it. Just to watch it. And I haven't seen any difference at all in the pace of the game, whether it's changing pitchers or between innings."

Well, for what it's worth, baseball's data shows that average spring training game times are down by several minutes. On the other hand, it's spring training. So nobody is pretending that means much of anything. The only part that's truly meaningful is this:

Baseball is trying.

It's trying to listen, trying to change, trying to adapt with the times, in more ways than one. It deserves a lot of credit for that. And much of that credit goes to the new commissioner, who has made that an obvious priority.

"I think it's important," says Rob Manfred, "for players and fans to have the impression that we're interested in hearing what they have to say about the game."

Well, as always, we're here to help. All spring, we've been asking players and fans, not to mention managers and umpires, what they think of the new pick-up-the-pace rules. So let's start with the most surprising thing the commissioner should know:

Despite all the clocks and all the hoopla, the differences in the game are almost imperceptible.

"I don't see a big change in speeding the game up," says Phillies manager Ryne Sandberg. "I haven't noticed that at all."

"To be honest, I don't even think about it," says Tigers catcher Alex Avila.

"I asked our guys not to let it rent space in their brain," says Nationals manager Matt Williams, "because if they're thinking about that, then they're not concentrating on the game itself. But we haven't had any issue. Everybody's playing the game like they normally play it. And everything's on time."

Average Time Of Game

All right, so now here's the big question: Is that a good thing or a bad thing? Is it great that the experience of playing and watching baseball feels virtually the same? Or does it tell us that these changes aren't really changing -- or fixing -- much of anything?

"Oh, I think it's a good thing," Manfred says. "When you make changes on the field, you want to proceed with caution and restraint, because you don't want to disrupt the play of the game on the field. You don't want people saying, 'Oh my God, the game's different.' "

OK, so the game hasn't felt a whole lot different. But have we mentioned in the last 30 seconds that it's only spring training? And March in Fort Myers has never been confused with September in Fenway. Even noted pace-of-game speed-up dissident David Ortiz reports he has been obediently keeping a foot in the box during spring training.

"But I don't give a f--- in spring training," Big Papi says. "I just want to get through my at-bat and get the hell out. So I'm there. I'm like, 'You ready? Let's do it.' But I don't know how it's going to be in the season, because in the season, I play to win."

So what will the new pace-of-game changes look like once the season starts? And what might be next after baseball spends a season easing all this into play? Let's take a look, after a spring spent surveying people all over baseball on what they're seeing and what they're expecting.

What's changing?

The three most important changes about to go into effect in 2015:

• With certain exceptions, hitters must keep one foot in the batter's box between pitches throughout their at-bat.

• Each ballpark will have between-inning countdown timers to ensure the next half-inning starts promptly. The timers will be set at 2 minutes, 25 seconds for most games, 2:45 for nationally televised games. Pitchers and hitters will both be encouraged to be ready to go when the clock reaches :20.

• Managers can now signal instant-replay challenges to umpires from the dugout area, instead of from the field.

Oh, and two more things: Once the phase-in period ends May 1, players can be fined up to $500 per violation if hitters don't follow the batter's box rule or pitchers aren't ready to pitch when the countdown clock hits zero. And umpires have been encouraged not to be confrontational in dealing with those violations. But privately, they're concerned that won't be possible. So that part will be, well, interesting.

Will the batter's box rule work?

Let's turn the floor over to Mr. David Ortiz, because he remains the most vocal cynic about the impact, and the fairness, of this rule. During a long conversation midway through spring training, Ortiz made all these pithy observations:

• "What made me angry was, whenever we want to talk about pace of the game, we just focus on hitters. The focus doesn't go to no one else. ... I see [pitchers] shaking their heads four, five times. That takes time, you know? And guys walking around the mound, thinking about what they're going to do. Which I've got no problem with. What I've got a problem with, is that's time taken away from the game. So how come it's always us -- the hitter?"

• "Why can't I [take time to] think and they [the pitchers] can? Because that's exactly what is going on in our head when we are coming out of the box. We're thinking. Our mind is spinning. And the pitcher's mind is spinning, too. That's why they take the time. ... My problem is, if you're going to come to me as a hitter and tell me what I've got to do, you should go to the pitcher and tell them what they've got to do so we are even. But if it's going to go just against us, I don't think it's fair."

• "I go with the pitcher's rhythm. But I'm not going to see a pitcher walking around the mound and I'm just going to be sitting in the box, just waiting for him to get ready. I don't know how that's going to work. You go fast for your thing? I'll go fast for mine. But if you're going to take your time, I'm going to take mine, too. Know what I'm saying? That's the way I think it should be. But we'll see. We'll see how it plays out."

Oh, we'll see, all right. But fortunately, most hitters have cooperated cheerfully so far. And most have quickly deduced, as Phillies third baseman Cody Asche observes, that "you can still dictate the pace of the at-bat" without leaving the box.

But as spring training went on, hitters began to figure out something important: If they keep even one toe in the batter's box, they can take just as much time to adjust their helmets and fiddle with their batting gloves as they ever did. So some people in baseball are already beginning to wonder if this rule will have any significant impact.

"A guy like David Ortiz can do all that stuff -- spitting in his glove, rubbing his hands, all that stuff -- with one foot in the box and still be OK," says one skeptical (and observant) baseball official. "So what did that [rule] do? It just keeps them from going outside the box to do it. It makes you wonder: Have the hitters beaten the system already? They're learning to."

Slowest Relief Pitchers In 2014

At an average of 31.1 seconds between pitches, Joel Peralta was the slowest reliever in Major League Baseball last season (minimum 50 innings pitched), according to Fangraphs.

Will the countdown timers work?

Here's our prediction: If baseball winds up shaving five to 10 minutes off the average time of game this season, the new timers will be responsible for most of it. And maybe even all of it. Here's why:

When MLB studied the actual time between innings last season, the powers that be were appalled to learn that breaks which were supposed to last two and a half minutes were often dragging three minutes and beyond. So it went to work on attacking that dead time -- no matter how much havoc the new timer might wreak on the Kiss Cam and those ever-popular "Don't Stop Believin' " sing-alongs.

"We don't need to be at 3:20 [between innings]," Manfred says, emphatically. "Why do we need to be at 3:20? And then that changes a whole set of dynamics. There's now timing on when the walk-up music has to stop. Which triggers the player moving out [of the on-deck circle]. Those are the kind of things that you can tighten up, shorten up, without affecting the flow of the game."

And not only have players not resisted this particular change, they're practically giving it a standing ovation. Before this timer started ticking, pitchers mostly had to guess how much time they had to get ready between innings. Now the guessing is over.

"Instead of looking at the umpire out there on second base and saying, 'Hey, what have we got here?' having that clock out there actually gives you some kind of idea," says Twins pitcher Mike Pelfrey.

The only area of worry we've heard from players and managers boils down to this: What happens if the pitcher or hitter isn't ready when the clock hits zero because of a legitimate baseball reason?

"The only time I think it's really going to be tough," says Tigers reliever Joe Nathan, "is if a new guy goes into the game and he gets to the mound and there's strategy to be talked about, because that's going to take away 30 to 45 seconds of a guy warming up, and the clock's still ticking, while people are having conversations on the mound about bunt defense or whatever you need to talk about before the catcher gets back there.

"So I hope that's the only time that the umpires and the players can be smart and not just have someone throw two warm-up pitches and [hear the umpire] say, 'Hey, OK, let's go,' and someone's going to get hurt. So hopefully, common sense comes into play."

Well, common sense is exactly what umpires say they've been told to apply to situations like those. But we all know some umpires got a better grade in Common Sense 101 than others. So, um, stay tuned.

Slowest Starting Pitchers In 2014

At an average of 26.6 seconds between pitches, left-hander David Price was the slowest starter in Major League Baseball last season (minimum 120 innings pitched), according to Fangraphs.

Will the new replay system work?

Matt Williams says he'll miss all that bonding time with umpires that the old replay system used to provide him.

"It was good," the Nationals' manager quips. "You got to know everybody's family, got to talk about the weather."

But now he'll just have to have those conversations while he's exchanging lineup cards -- because the days of managers ambling out to kill time, while their replay man is deciding whether to challenge a call, are officially defunct. And guess what? Nobody will miss that. Any of that.

Now, though, here's the bad news: How much time will the new replay system really save? Our guess is just about none.

Williams says he's hopeful that making challenges from around the dugout could save a couple of minutes, "because if we have a quick call from the video guy, we can just say, 'OK, let's go.' We don't have to go all the way to first base from the third-base dugout."

But in truth? We doubt it. Managers say they haven't been told to make their challenges more promptly. So that won't save time. And even if they don't have to walk all the way out to the spot of a call and then walk all the way back, that's overrated, too. If they issue a challenge, the crew chief still has to trot in from whatever base he's working and put on the headphones. And, by the way, baseball officials still believe that most replays will still require the manager to inform the umpire verbally of exactly what he is challenging. Which means he'll have to leave the dugout anyway.

"So really, what's this system going to save?" wonders one skeptic who doesn't want to be named. "Maybe a few seconds?"

Will there be more subtle changes?

Here's something to watch for that nobody has talked about:

Two managers say they ran into instances this spring where umpires thought pitchers were taking too long between pitches. They were then informed that the umps have been encouraged to enforce the longstanding but also long-ignored rule that requires pitchers to deliver a pitch within 12 seconds with no one on base.

"The guy just signaled out to my pitcher, 'C'mon, there's nobody on base. You need to deliver a pitch,' " one of those managers reported. "And he [the pitcher] was just out there getting sweat off his arms. So I went out just to see what he was yelling at my pitcher about. And he said, 'Well, with nobody on base, they have 12 seconds to throw a pitch.' I said, 'Well, I didn't get that memo.' "

Turns out, of course, that nobody in baseball got that memo. So let's ask the commissioner about it.

"Well, it is a rule, right?" says Manfred, with a soft laugh. "It's a rule that's been on the books for a long time."

On one hand, Manfred admits, there has been "no change with respect to enforcement" of that rule. On the other hand, however, he says, "I think that the focus on pace of game has just caused everyone to be a little more cognizant, not only of the changes that we've made but the things that were already in place."

So the impetus, he says, will be on "raising awareness," not enforcing unofficial pitch clocks. But baseball will be compiling data on how long all pitchers take between pitches this year, mostly for informational purposes, while 20-second pitch clocks tick at the upper levels of the minor leagues. So that can't help but make us wonder ...

What's next?

Face it. This was the easy part of fighting the pace-of-game war. So what does that tell us about the hard part? That everything else is the hard part. And no one knows what comes next. And by no one, we even include the commissioner of baseball.

Ask him what he thinks is coming next, beyond this year, and Manfred says: "Just too early to tell on that one right now.

"I think that our approach, with respect to pace of play, has been: Let's make a set of changes that we're comfortable with, see what results we get and then evaluate whether -- and when -- something else needs to be done."

So before we speed ahead to pitch clocks and who knows what else, can we spend a few months and see how this season goes first? That's where Manfred stands. And the players' union, not surprisingly, is in even firmer wait-and-see mode.

"Having the words on the paper is one thing," says the union's executive director, Tony Clark. "Seeing them manifest themselves on the field can oftentimes be a little different. And that's where we're at. Guys are acclimating themselves. And we're hopeful that as we get through spring training and the first month of the season, guys will get comfortable with what this is, because if they're not, then it's affecting the game on the field, the game that the fans are coming to watch."

And lest we forget, there's one more party that will be watching closely -- the umpires. We'd better not overlook them, because they're right in the middle of this fray.

Publicly, they're on board. Privately, they're nervous. Nervous that they're being asked, on one hand, to play cops patrolling a dangerous beat but, on the other hand, not to be confrontational. So if they feel they're not getting the backing they need to make these changes work, they could make waves over any further tweaks themselves.

So that's the context for everything that's about to unfold over the six months ahead -- and everything that could be talked about just over the horizon.

Those 20-second pitch clocks in every Double-A and Triple-A park in North America might give you the impression that pitch clocks in the big leagues are practically a done deal. But even the commissioner, when asked if he thinks those clocks are inevitable, says: "I don't," even though he also says he was "encouraged" by the pitch-clock experiment in the Arizona Fall League.

Maybe he'll be more encouraged after the minor league trial period this year. But major league players are going to continue to be a tough sell on that one.

ESPN The Magazine: MLB Confidential

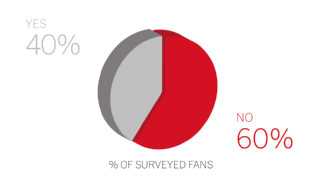

Yes or No: I Like The Idea Of A Pitch Clock

"There are parts of the game," says Phillies pitcher Kevin Slowey, "where, when I watch a game, I enjoy seeing a guy step out, seeing the catcher put down a bunch of different signs, having a pitcher shake all the way through, going out and talking to him. You see that, that's part of the game.

"At times, that's the crescendo of the symphony," Slowey says, sounding kind of like the host of "Masterpiece Theater," "that seventh or eighth inning, where the setup guy has got a runner on second and third and you want that to last as long as you can. That is the crescendo. You want that ... to be where that whole game boils down to that minute and a half. So if you were to say to a pitcher, 'You only have 30 seconds to throw that pitch,' you may speed that music up to the point where it's no longer beautiful to you."

What was fascinating this spring, though, was that we heard far less conversation about pitch clocks than we did about another development that is slowing the sport to the approximate pace of a 5:30 p.m. rush-hour freeway jam: mound visits.

"I'll tell you what," says Big Papi, more animated than ever now. "If they want to shorten the time, they're going have to cut down on the visits to the mound, because that takes time. That takes 15 to 20 minutes -- an inning."

According to play-by-play data analyzed by ESPN Stats & Information, there were more than 9,400 mid-inning mound visits by managers and coaches alone last season. That computes to almost four per game. And that doesn't even include visits by catchers and infielders, which are estimated to be in double digits every game. But there is a potential solution to cut down those visits, says Yankees manager Joe Girardi.

"I'm a big fan of Bluetooth," Girardi says. "I think it's the world we live in. They do it in football. And they do it in all these other sports. And I think it could serve our game really well.

"You could either have a button you push, something on your belt and you push it, or look, we have security guards that ... put their wrist in front of their mouth and then they talk and no one hears what they're saying. So I think it would definitely work."

Cool, huh? If Jack Bauer can save the world while yakking to his buddies at CTU on his Bluetooth, why can't, say, Motorola save baseball with the same technology?

"Well, then, all of a sudden, teams would be hiring lip readers," Girardi chuckles. "But you've just got to cover your mouth."

Would pitchers really agree to wear earpieces? Would teams respond by installing secret listening devices underneath home plate? Would any of this actually be workable? Girardi says he would "love to see us try it in spring training." But he should know that not everyone is ready to go that high-tech.

"To be honest with you," says Avila, "when a catcher runs out there to change a sign or talk about a pitch, I don't see what the big deal is about doing that. It's part of the game. It's been like that for 100 years."

Oh, we're pretty sure there are going to be about 75 billion more mound visits this year than there were in 1915. But whatever. This is important, Avila insists. In a big spot, in a big game, the pitcher and his catcher need to do whatever they can, he says, to make sure the next pitch is the right pitch.

"The game is not supposed to be played in a rush or a hurry," he says. "There are things you can do that maybe help out, like they've been talking about the batter's box rule and that type of stuff. But when you start adding things that will drastically change how the game is played -- not the pace of game, but literally how the game is played by the players -- then I think there's a problem there."

And guess what? It's a problem that will always hang over the quest to speed up baseball games. So let's finish by asking:

What's not next?

You want to know the real reasons baseball games take so much longer now than they did 20, 30 or 40 years ago? Let's put it this way. They have very little to do with hitters wandering out of the batter's box and spitting into their batting gloves.

It's TV commercials. They're not going away.

It's the explosion of mid-inning pitching changes. Good luck making them go away.

It's Sabermetrics, which drive matchup baseball in the late innings. And more pitches per plate appearance. And fewer swings. And hot-zone, cold-zone hitter-pitcher info that is leading to more whiffing and fewer crooked numbers. Does anybody see an end to the information age approaching any time soon?

The point is that baseball can't possibly do a whole lot to address any of that. So it's faced with the challenge of trying to evolve along with a faster-paced society without destroying the essence of what makes the game great when it's at its best.

"There are parts of the game of baseball that are beautiful because they take time," says Slowey. "And then there are parts of the game of baseball that take time and may not be beautiful, but they're still part of the game. And then there are parts of the game where you say, 'Can we make this better in some capacity?'"

ESPN The Magazine: MLB Confidential

Yes or No: Baseball Games Are Too Slow

The debate over which parts to mess with and which to leave alone is a hard one. But the commissioner assures us that no one is more in tune with that than him.

"Whenever you talk about changes in the way the game is played on the field, you have to balance the history and traditions of the game against the need to modernize," Manfred says. "And I think, with the set of changes that we adopted this year, we're trying to deal with down time that we do not see as integral to the history and traditions of the game, because we are never going to fool with those issues."

The commissioner is certainly astute enough to know that if the average baseball game ends at 9:57 p.m. this season instead of 10:07, it isn't going to magically turn millions of 30-somethings into passionate baseball fans. That's a battle that has to be fought well beyond this battlefield. We'll get into that battle some other time.

In the meantime, for him, the success of the new pace-of-game push is not going to be measured strictly in minutes and seconds. And thank heaven for that.

"I'm really not thinking about this in terms of average game time," Manfred says. "It's not like I have in my head I want to get from 3:02 to 2:58 or 2:55. That's not what it's about for me.

"What I hope happens, is that, at the end of the season, knowledgeable baseball writers and fans are saying, 'You know, they got this one right. There's a crispness to the play. They've cleaned up some dead time in the game. And maybe best of all, we feel like they were responsive to what people were saying about the game.' "