|

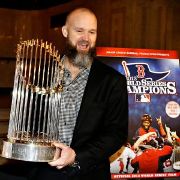

PITTSBURGH -- Her name is Colleen, and she came here with her father. A high school soccer player, Colleen had taken a kicked ball to her face from very close quarters and has been suffering from migraines ever since. His name is Brandon, and he came here with his mother. He is a high school running back who lowered his head as an onrushing tackler approached and collided helmet to helmet, with such force that he was left with a lump under his helmet. For Brandon, the headaches were the least of it. "I felt like I was on another planet," he said. "It was just like a weird feeling. I didn't feel like I was fully there. I felt like a walking zombie all day at school."  On the hallway walls are the jerseys of professional athletes, football players and hockey players and baseball players, including two from the Red Sox, David Ross and Stephen Drew. There are inscriptions on both of the Sox jerseys. "Mick, you are a man's man," Ross had written. "Thank you for all you did for me." "Mick, thanks for all your help," was the message left by Drew. "All the best." All of them -- Colleen and Brandon, Ross and Drew -- have come here, to the University of Pittsburgh Sports Medicine Concussion Program, for the same reason: They were showing concussive symptoms, and they all had been referred to Dr. Micky Collins, a former University of Southern Maine baseball player who fell in love with the study of the brain and now promised his patients that he possessed the tools to control those symptoms -- and in most cases make them go away. "I always promise my patients four things," Collins said here this week. "No. 1, I'm going to explain why they're feeling what they're feeling and can show that to them. We can reproduce that with the evaluations we do. "The second promise is they're going to get better through rehabilitation and treatment, no matter how long it takes. "Third, we're not going to push you back until you're ready. And the fourth thing is, we're not going to hold you back a day longer than necessary. It's going to be handled the right way." It doesn't happen on one visit to Collins, the clinical and executive director of the concussion program, who also serves Major League Baseball as a consultant. Red Sox infielder Brock Holt, who has not played since Sept. 5 after complaining of dizziness, saw Collins for a second time on Thursday, and while he showed improvement, Collins was not ready to give him the OK to return to playing. Last summer, Ross was placed on the 60-day disabled list and came to Pittsburgh four times before he was cleared to play. "We're getting so much better at treating this stuff," Collins said. "There is so much neurological mythology, the perception in sports that concussions are unmanageable and you're all going to end up with problems. "I don't see that. I see a manageable problem that is treatable and by gum, we're getting better at it every day. I don't feel there's a patient I can't treat. We've learned how to attack this thing and understand it breaks into different types of concussions." Many concussion symptoms are widely known: unconsciousness, of course. Balance issues, dizziness, memory loss, vision problems, headaches.  And then there are the ones that are less known, the kind that Ross, struck in his catcher's mask by multiple foul tips, never imagined were connected to his concussion until he visited Collins. "I would cry at the drop of a hat, cry over nothing worth getting upset about," Ross said Thursday while sitting in the visitors dugout at PNC Park. "I felt at times really, really agitated at my kids. I didn't have much patience for them during that time. "I would tell them not to do something, and they would start crying because of the look on my face. Kids are so attuned to how you look, and my wife would have to tell them, 'Dad's not getting on you. He's just got a headache.'" Ross's wife, Hyla, saw the difference in her husband, and was worried. She would ask him again and again if he was all right, until he finally snapped at her and told her to stop, that he was fine. "The final straw for my wife was we went over to an area [where] we like to eat," he said. "I didn't realize I'd go into a restaurant and lose my appetite because of all the [commotion] around me. "We were headed back and a guy cut me off in traffic. I flipped. I'm not an angry person, but if that guy had gotten out of the car I would have tried to beat the s--- out of him. I would have tried to hurt him. I scared my wife. She said, 'You're out of control.'" She also made it clear to Ross that if he didn't talk to the Sox medical staff, she would. "My wife said, 'You're not behind your eyes. You're there, but you're not there.' Only the people who are close to you know that." Ross already had gone on the seven-day disabled list once, and thought he was getting better. Then he got hit again by a foul tip in Baltimore, and he knew he was in trouble. It wasn't just the drastic mood swings. "After the first little ding in my head, I thought I was just off in my timing," he said. "I would see the ball when I was hitting but when I'd go to swing, it kind of disappeared. I'm thinking, 'Man, what's going on? I tried to slow things down, tweak my swing, and nothing was working. I struck out five times in my first game back from my first concussion, and thought I was rusty. "I came back and watched a film of a game where I went to throw a guy out at second and threw the ball into right field. And I remember coming to the yard, and I'd have two Red Bulls and a 5-Hour Energy drink because I felt responsible to come to the field and bring energy to the dugout and cheer on my teammates. I actually feel that's a real important thing, but trying to do that was just such hard work. I'd get overwhelmed by the headaches. "That's when the light started coming on for me." As his wife had requested, Ross came to Fenway Park and sought out team medical director Dr. Larry Ronan during batting practice and told him that his wife had asked that he speak with him. Still, when Ronan inquired how he was, Ross said he was fine. "As athletes," he said, "we feel like we can push through anything." He remembers thinking when he'd hear of another player having a concussion, "What's the big deal? Just push through it." Ronan did not take Ross at his word. He called Hyla, and after speaking with her, came and pulled Ross off the bench. "Hyla was crying," Ross said. "She felt like she was throwing me under the bus. She knows how important baseball is to me, and my team. "It still makes me emotional to talk about it. I was batting .200, but we were winning and I was trying to get it going. One thing you learn is to count on your teammates. Good season or bad season, we're all in this together and we're going to grind it out. I felt like my teammates would think I'm bowing out because I wasn't hitting. That's what I worried about: It would kill me inside if my teammates thought I was bowing out."  And that's when Micky Collins came into his life. "Going in and talking to him -- my wife was there with me -- I remember getting emotional, telling him how I was feeling, listening to my wife," he said. "I finally let my guard down a little bit. I remember him doing some tests. The best thing I can say about him and the facility is they show you that you're hurt. "I just remember he showed me how bad off I was. They ran me through a full day of tests. I remember leaving there drained. We were in the Pittsburgh airport, and my wife went to get food. I laid my head down because I couldn't take it anymore. I needed to rest." Collins has an easy way with people. Joking with his patients is second nature to him. He is informal but direct, one of those people who can make you feel that there is no one more important in that moment than you. "He cares so much," Ross said. "That's so easy to see." The scientific jargon is kept to a minimum. Concussion? "The brain is like an egg yolk inside an eggshell," he said. "There's not much we can do to prevent that egg from moving inside the skull. I don't care what you wear on your head." Oh, he'll tell you about the billions of neurons in your brain, and how the membranes of those cells get stretched when there is a concussion, allowing the potassium in those cells to leak out and the calcium to leak in, and the metabolic crisis that ensues. But more importantly, he wants you to understand there are different types of concussions, primarily identified by the symptoms exhibited. "Your ability to move your eyes, bring your eyes together. For a baseball player, that's their money. Ocular functions," Collins said. "The vestibular system, we're learning that's where the dizziness comes. It controls your ability to coordinate hand-eye movement, it stabilizes your vision when you move your head. That's where a lot of patients have problems. We actually know that system extraordinarily well. We can show the patient where he's hurt. "Then there's the cognitive stuff [memory], migraines and neck issues. If you understand this chessboard, you can get to the injury for every patient. Sometimes they have all six going on. David had all six. He was just jacked up." Collins and his clinicians have devised a series of procedures that allow them to quantify those symptoms, the most prominent of which is called VOMS (vestibular ocular motor screening). "We can quantify things with an eye chart test we do," said Dr. Anne Mucha, clinical coordinator of vestibular therapy. "How well can you see when your head is moving at a velocity we can standardize. What happen when we look at your eyes in the dark. We put video goggles on people, so we can do tracking, testing, looking what's happening there. A series of balance tests that gives us more specific measures, and then we devise how we're going fix it."  Collins employed some of the VOMS techniques with both Colleen and Brandon, asking them to place their thumb in front of them and track it with their eyes as they move it back and forth at rapid speed. Another exercise involved a popsicle stick with a dot that he brought close to their faces as he watched their eyes. Simple stuff on the surface, but with demonstrable results. Then there is exertion testing that all patients must pass before they are cleared. The first time Ross underwent his exertion testing -- "stuff I should have been able to do in my sleep" -- he vomited in a wastebasket. Much of the testing involves balance and movement. Taking three steps while looking up, taking the same number of steps looking down, starting in a catcher's crouch and moving laterally while looking side to side, up and down. Walking around and stepping onto boxes. The patients who exhibit dizziness symptoms, Collins said, have been shown to be the ones who typically need the most time to recover. But they will recover, he promises, if they follow the program of exercises they are given. Ross not only recovered after being sent home in the middle of the summer, taking him out of an environment that he could not handle in his condition, but he came back to play a critical role in the postseason, catching on a nightly basis through the American League Championship Series and World Series. "When I caught that last out," Ross said, "I felt an overwhelming sensation to thank God. I told the umpire, 'Nice job,' then 'Thank you Lord, I can't believe this is happening to me' kind of thing. "Amazing. It's like seeing a movie you wouldn't believe. Who could believe that I couldn't play with my kids without getting dizzy at home, and then I'm catching the last out of the World Series. Crazy." That wasn't just in his head, you might say. But actually it was. And there's a hallway in a Pittsburgh clinic where Ross lets you know who was responsible.

|