|

THE LOST PITCHER had many needs. He had lost so much: his old fastball, the slider that repelled bats and the brashness that sustained both. Somewhere inside him he knew they were alive but inert, lying in wait, existing in an extended state of torpor. To wake them, he had one need that rose above all others: silence. He needed silence as an asylum from judgment and expectation. He needed to be alone with his doubts and embarrassment and confusion, to retreat from the well-meaning cacophony of advice, away from the Angels' stadium parking attendant who told him he needed to keep his front side closed a bit longer, away from the usher who thought his stride was too short, away from even his father, who said he'd be every bit as proud of his son if he never threw a baseball again. Yes, Scott Kazmir needed the noise -- the infinite chirping of an infinite number of birds -- to cease. He needed the only voice in his head to be his own. The lost pitcher was just 27 years old, released and adrift, a former American League All-Star and strikeout champion. Jobless and verging on hopeless, he had no idea where any of this would lead. He just knew it would lead nowhere if the noise continued. Silence can be a challenge. The world is a discordant concert of pings, alerts and notifications, each representing validation and reassurance. Someone out there cares. Silence can be easily mistaken for ostracism. Silence is an indictment. Now, attempting to find anchorage, Kazmir stood on the mound he had built in his suburban Houston backyard. It was early morning, somewhere in the half-dark middle ground between night and day. He stood out there in the thick Texas air and threw, sometimes closing his eyes between pitches, waiting for the old synapses to reconnect, for the body to reorganize and remember. There was something about the stillness, the remove, the separation from the rest of the world. In the meditative peace of his own thoughts, it was just him and the catcher's mitt, the silence broken only by the sound of ball hitting leather. It was here, in the offseason of 2012, that Kazmir could evict the self-loathing and self-doubt. It was here that he could add links to a chain that might propel him forward, back to his old self. The right leg spiked the air like the whip of a reptile's tail, just like the good days. The hands broke and the arm swung and the body accelerated down the mound with a gymnast's grace. In the quiet, he listened to nothing at all.

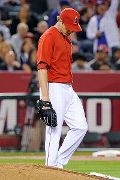

HE WAS LIKE an amnesiac retraining himself to perform basic tasks. Everything that used to happen so easily was suddenly foreign. How did this happen? How did one of the best left-handed starters lose every single bit of it -- velocity, command, feel, confidence? It's nearly unprecedented: in the big leagues by 20, a two-time All-Star by 24, out of the game by 27 with no obvious injury to blame. Kazmir had always been something of a physiological mistake. He seems a better fit for soccer or swimming, or maybe dentistry. Barely 6 feet, around 185 pounds, his body was like a tight spring, uncoiling down the mound in double time to release a ball with easy force. He threw three straight no-hitters at the highest level of Texas high school baseball and, he says, barely missed a fourth. He became a cult figure for self-flagellating Mets fans after the team that made him the 15th pick of the 2002 draft traded him two years later to Tampa Bay for immediately forgettable Victor Zambrano. In Tampa, he became a good pitcher on a bad team, then a good pitcher on a World Series team, before being traded to the Angels during the 2009 season. He was not known for a particularly cerebral approach to pitching. "When I got in trouble, I just tried to throw harder," he says with a shrug. If he didn't know what he was doing when he was doing well, how was he supposed to know how to fix himself? In 2010 with the Angels, the slide began. He was 9-15 with a 5.94 ERA, striking out 93 and walking 79 in 150 innings. It's difficult to overstate how quickly and thoroughly Kazmir disintegrated. His fastball velocity dropped -- from 91 mph to 87 in two seasons -- as his control worsened. Advice came at him like a constant wind. Something about Kazmir's boyish look made people desperate to help him. "It was all really good stuff to tell someone," he says. "But at the time, it felt like information overload."  His agent, Brian Peters, and his trainer, a plainspoken Texan named Lee Fiochi, sought professional help. Kazmir got permission from the Angels to visit Ron Wolforth, a pitching iconoclast who operates out of a 20-acre ranch in the swamps and pines of the Houston exurb of Montgomery. To exorcise pitchers' demons, this Col. Kurtz-like man employs funky techniques in his Quonset hut laboratory, set back off an unlit, winding road. Kazmir, in what he terms his denial stage, couldn't quite wrap his conventional mind around the unconventional drills. After an introductory session, Kazmir decided Wolforth's plan wasn't for him. After a disastrous spring training, Kazmir made one start for the Angels in 2011: five runs, five hits, two walks and two hit batters in 1 2/3 innings on April 3 in Kansas City. He ended up in Triple-A, where he threw 15 1/3 of the worst innings ever: 20 walks, six hit batters, five wild pitches and a 17.02 ERA. On June 15, he was released. "It was almost a relief," Kazmir says. He had fooled himself into thinking he was close, that with a tweak here and there he'd be fine. He continued to throw throughout the summer of 2011 and decided to go to the Dominican Republic for winter ball in December. The result? One start, one out. "Another disaster," he says. He went home, took his boat out onto Lake Conroe and told his father, Ed, that he and his friends were welcome aboard under one condition: no baseball talk. Ed Kazmir, a factory supervisor, agreed but told his son: "You done great. Family's proud of you. You've had a good career. Lot of guys haven't done half of what you've done. You pitched in a World Series, led the league in strikeouts. You've made enough money to retire." It was a father's way of telling a son that it was OK to walk away from a lost cause. Sometimes, in the interest of self-preservation, it's best to get out of the way. Maybe it was just gone, Ed Kazmir seemed to be saying. Poof -- no more 97, no more wipeout slider. Maybe it just took this long for physiology to win. The case of Scott Kazmir seemed to be no cause and all effect. Nobody knew anything. The son nodded at his father but didn't listen. "I almost felt like I wanted to give up," he says. "I wanted to be able to accept it, but there was no way."

THE 55-YEAR-OLD man with the Quonset hut looks a little like Phil Simms and talks a little like Tony Robbins. Ron Wolforth is something of a general contractor, specializing in rebuilding broken-down pitchers through guidance, motivation and the occasional straight shot of tough love. He studies biomechanics yet despises absolutes, which results in a teaching approach that relies more on suggestion than dogma. Wolforth is a former low-level college pitcher who runs the Texas Baseball Ranch, the closest thing baseball has to a cult. Down a winding country road, there's the 20-acre ranch with a faux barn office, that open-ended corrugated steel hut and a makeshift diamond. It is, as Wolforth admits with a laugh, underwhelming digs for a cult leader. His followers, though, are rabid. The first time Angels lefty C.J. Wilson came to the ranch, he was so excited that he got off a plane at 10 p.m. and called Wolforth to tell him he was on his way. Wolforth tried to dissuade him, telling him he should wait until daylight, but Wilson insisted. Because baseball is a hidebound institution, some devotees of the Ranch hide the affiliation. Wolforth's clients have been known to do his eyebrow-raising drills in hotel rooms rather than in bullpens, where such tools as the shoulder tube -- used for warm-up drills that can resemble baton twirling -- might raise a skeptical eye. "It scares baseball a little bit," Wolforth says. "It's like they think I've got some Kool-Aid in the back, so if it doesn't go well you can go back there, drink it and end it all." About four months after Kazmir's June 2011 release, Wolforth received another call from Fiochi; Kazmir's trainer, as desperate as the pitcher himself, wanted to re-enlist Wolforth's help in an unlikely resurrection. With more time available to him, Wolforth approached the Case of the Lost Pitcher like a forensics expert. Gimme everything you got on Kazmir. He looked at videotape from high school. He dissected film from Tampa Bay, where Kazmir peaked in 2007 with a 13-9 record and an American League-best 239 strikeouts. And like a connoisseur of horror films, he pored over video of Kazmir's work in his 35 starts with the Angels. Almost immediately, Wolforth saw that Kazmir had lost contact with everything that had brought him success. Simple tasks were a struggle. He was so unsure of his delivery -- and so desperate to remember -- that he started his motion with the ball in his hand, separated from his glove, and slapped the ball against the glove when he thought it seemed time to break his hands. Whenever he tried to throw hard, he yanked his front side open so violently that the ball would sail into the right-handed batter's box. "He had no confidence," Fiochi says. "He didn't know his head from his ass."

WOLFORTH'S EXPERIENCE WITHs with pitchers has taught him a few ironclad truths: They lie. They deny pain. They refuse to leave games when they know better. They risk long-term health for short-term gain, all to avoid being marked with the vilest label: soft. Kazmir denied pain. Wolforth expected as much. "It's like asking a marathon runner: 'Do your legs ever get tight?'" he says. Of course they do. Prodded, Kazmir started to remember. He strained his triceps in 2007, just before the All-Star Game, and he changed his delivery to compensate. As a result, he strained his groin. He pitched through it, shortening his stride to offset the pain. His fastball lost a few feet, but his changeup got better and he reeled off six straight wins. But each change created the need for more change. It was as if he were shoving the wrong pieces into a puzzle and convincing himself it matched the picture on the box.  Wolforth put Kazmir through core-strengthening workouts and gave him drills to loosen his hips and increase leg drive. "If you've got a flat tire," Wolforth says, "I don't care how big of an engine you've got." A scout told Kazmir that he should reinvent himself as a LOOGY -- a left-handed one-out guy. You aren't you anymore, the scout was really saying. Deal with it. "I know what I'm capable of doing," Kazmir replied. "I know what my body feels like, and I have more in the tank than even during my best years." He knows how delusional that must have sounded back then, the guy with a high school fastball he couldn't control telling everybody he can be better than the guy who threw 97 mph and led the league in strikeouts. Scouts and coaches treated him like the slow kid who tells his parents he wants to become a doctor. "They'd give me a little half-smile," Kazmir says, "as if to say, Yeah, Scott, just keep telling yourself that." Maybe what baseball people say is true, Kazmir thought: Velocity lost is never regained. Maybe former Angels teammate Dan Haren was right when he said, "Whether it was him not accepting he doesn't throw hard anymore or still trying to figure out how to pitch at 88 mph, it never came together for him." Maybe reinvention was the only way back. Then one spring day in 2012, Wolforth showed up for a workout at Kazmir's house carrying a radar gun and a challenge. "All right, Scottie," he said. "It's time to hit the gas."

THE RADAR GUN represented judgment and expectation. It was a proxy for every scout, every pitching coach, every general manager who had a say in his future. A boss had entered the room. "He was in a dark mood," Wolforth says. "That's a painful reminder of what he used to be." Velocity has become pitching's lingua franca. As a young pitcher throwing in the mid- to high 90s, Kazmir benefited from baseball's genuflection toward the radar gun. As a reclamation project throwing in the mid-80s, he faced a harsh reality. "You can have the best location and best movement in the world," Kazmir says, "but if you're not lighting up the gun, you're not impressing people." And there before him stood the proof: Wolforth, gun in hand, expecting backlash. "That thing doesn't tell whether you can get big league hitters out," Kazmir said. "I don't doubt that," Wolforth responded, "but big league teams see you as damaged goods at 88. You were Moon Valley prom queen, and now you're trying to tell them you have a good personality?" Kazmir threw the first pitch. "What was that?" he asked. "Eighty-two," Wolforth said. Kazmir swore and snapped the return throw out of the air. Convinced that Wolforth's old-school gun was wrong, he bought his own, a state-of-the-art Stalker. Before a bullpen session a few days later, he gave it to his girlfriend, Kim Seitler. After one pitch he thought, That one came out good, so he asked Seitler what it said. "Eighty-three," she told him. "You know what?" he said. "Just put that away and go inside. We're good." Something happened, though: The gun became an opponent, a stand-in for every hitter he'd ever sent back to the dugout, and the lost pitcher began to find himself. With every uptick -- 86 by the end of the first day -- he started to feel the old connections. His normal 25-pitch bullpens became 100-pitch marathons. He improved his diet. He threw early-morning sessions in the backyard. In the evenings, he'd hop the fence of a nearby baseball complex like a little kid. "He didn't want to stop," says Kevin Poppe, his sessions catcher. "That's when I knew it was going to happen." About a month after Wolforth shattered the serenity with the radar gun, Kazmir threw a fastball and the readout flashed a magical number: 90. There was a celebration in a minor key, fist bumps all around, and Ed Kazmir says: "Wish I'd been there. I'da cracked open a beer." Roughly three months after the appearance of the gun, Kazmir signed with the independent Sugar Land Skeeters. In a start at Bridgeport, Conn., he found himself staring into a radar-gun readout directly behind home plate. "I didn't even have to turn around and look for it," Kazmir jokes. He sat at 88 to 89 through the first couple of innings. He threw a first-pitch fastball to a lefty and saw 92. "Through the rest of the at-bat," Kazmir says, "I saw 95, 95, 95." The radar gun, friend turned enemy, once again became a friend. He stood

on the mound, took a deep breath and tried not to smile.

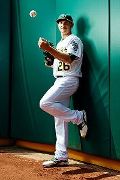

THE RESURRECTED PITCHER had gained so much: perspective, maturity, humility. "I don't know if you have time for all of that," he says. He doesn't own the words to explain the psychological side of it, the control and focus he never knew he could take to the mound. He used to look away throughout his windup and find the target as his front foot landed. Now he locked in on the mitt and never let go. A bad pitch would give birth to three or four more; now it was corrected immediately. He could take no more noise, and when he silenced the radio static playing ceaselessly in his head, he discovered the one quiet voice he'd been ignoring all along: his own. Kazmir earned a spot in the Indians' rotation in 2013 as a nonroster invitee and went 10-9 with a tremendous second half. The Athletics, whose front office is known for foresight, keen analytics and a nose for a bargain, signed him to a two-year, $22 million contract in the offseason. "The biggest piece of analysis we did was try not to outthink ourselves on it," says A's assistant GM Farhan Zaidi. "We saw a guy who was relatively young, who had good stuff, who had good numbers, who was a good fit for our park. We might not have viewed what he did in 2013 with the suspicion that some other teams did." The A's looked at Kazmir's strikeout-to-walk ratio in the second half (82 K's, 17 BBs) and his velocity readings (average fastball: 92.5 mph) and took them at face value. They didn't ask where the velocity came from (a hut in the sticks might have raised more questions than answers) because they saw it as recovered rather than created. The A's now look prescient. Through mid-June, Kazmir was 8-2 with a 2.05 ERA and an 0.98 WHIP. His strikeout-to-walk ratio (3.6 to 1) was the best of his career. Kazmir has been nothing less than one of the best and one of the most efficient starters in baseball this season. "He lost his way a little bit, and that might have been the best thing that could have happened," says A's manager Bob Melvin. "It's a rare story." Nearly three years since being forgotten and discarded, now 30 years old, Kazmir stood on the mound on a pleasant late-May night in Oakland and pitched against the Tigers until the game was over. His first complete game since 2006 -- and just the second of his career -- was a symbol of an unlikely resurrection, but it was more than that. It was a ceremony of sorts, a nine-inning observance of a completely new man. Through 103 pitches -- "He was throwing 40 an inning there for a while," Ed Kazmir jokes -- he wound his way through Miguel Cabrera and Victor Martinez and Ian Kinsler, with the only glitch a Torii Hunter solo homer. "I visualize each pitch before I throw it," he says. "If something doesn't go right, I can fix it right then and there." He can summon 95 when needed, but his changeup has become his best pitch. He induces more ground balls. He reads hitters. He pays attention. Instead of answering force with more force, as he would have done during his previous incarnation, he has learned to use the hitter's aggressiveness against him: pitching as martial art. After he beat Detroit, he had a conversation with his father and fielded congratulations from Poppe, Fiochi and Wolforth. Their words were muted, though, free of the surprise of the uninitiated. Theirs were the words of the believers, those who heard the noise and came to appreciate the gift of silence, the beautiful roar of nothing, absolutely nothing at all. Follow The Mag on Twitter (@ESPNmag) and like us on Facebook.

|