OAKMONT, Pa. -- Dwain Landry always loved talking golf with his kid, Andrew, an undersized boy who grew up on a nine-hole course the locals in Groves, Texas, called the Pea Patch, where chip shots were often played from mounds of spiked-up dirt. But when father and son spoke recently about the next tournament to come, the circumstances and stakes were unlike any they had confronted in the past.

Andrew was no longer playing mini-tour events in North or South America, or NCAA matches at Arkansas, or friendly neighborhood games at the Pea Patch, a shuttered track that Landry's college coach, Brad McMakin, called "a rinky-dink place where they might use coffee cans as cups to hold the flagsticks."

Landry was about to compete in his first major, the U.S. Open, and yet he'd lost none of the blind faith and competitive fire that had elevated him above his physical limitations.

"Dad," Landry told his old man, "I'm going to win this tournament."

"Drew," the father responded, "I have all the faith in the world that you can do this. You're just as good as the rest of those guys out there."

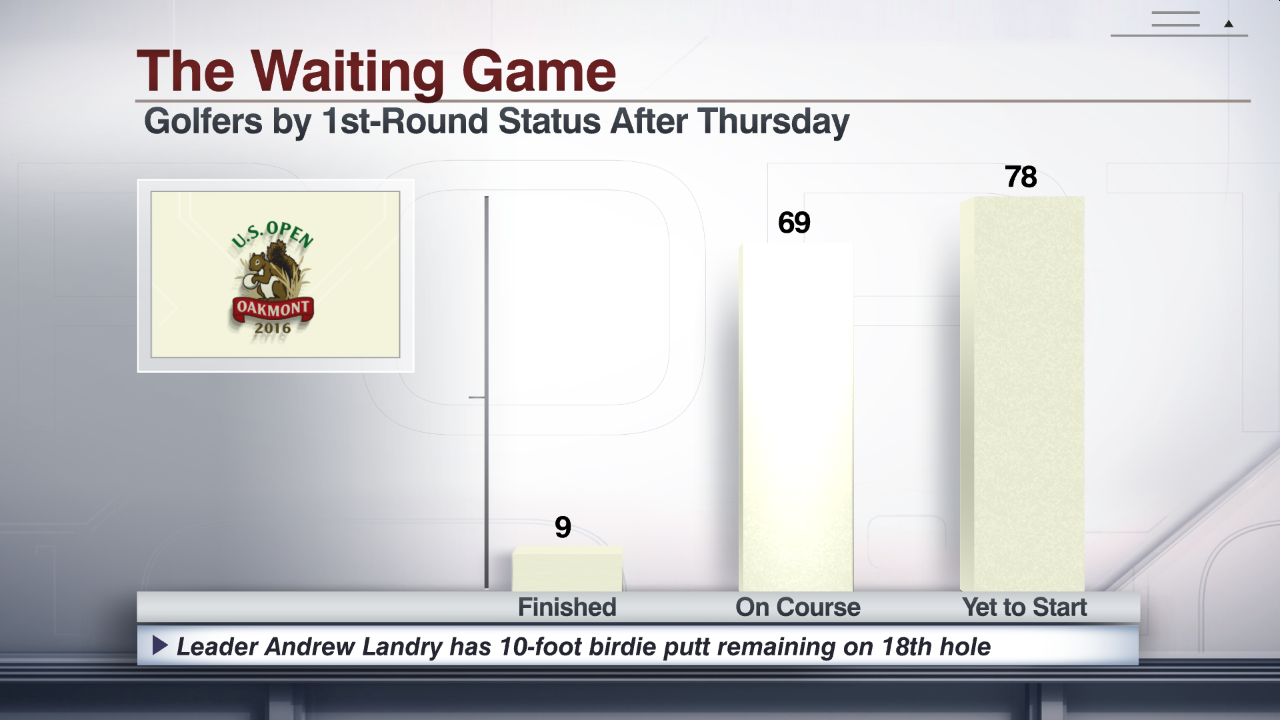

As it turned out Thursday, Landry was better than the rest of the guys who got a chance to play Oakmont as storms rained all over this major championship parade. Nine players finished their rounds, dozens never made it to the tee box, and when this endless bummer of a day was complete, the name atop the leaderboard wasn't McIlroy or Spieth.

It was Landry. Andrew Landry. A 28-year-old PGA Tour rookie, a player ranked 624th in the world, and a guy who once shot 58 on two trips around the Pea Patch. If you'd heard of him before Thursday, you either live within a 10-mile radius of Groves, or you probably spend a little too much time watching Golf Channel.

That's OK; the rest of America knows him now. Landry hadn't shot lower than 68 all year, and yet as he stepped into the first round's third and final rain delay, he left behind a leading score of 3 under and an ultra-makeable birdie putt on his last hole. He drained it Friday morning, giving him a 4-under 66 on perhaps the world's toughest course.

Think about that. Tiger Woods' best score at Oakmont in 2007 was a 69, the same personal best posted by Sam Snead, Tom Watson and Seve Ballesteros in different years. Jack Nicklaus and Arnold Palmer never shot better than 68 in a U.S. Open here, and Ben Hogan and Gary Player never shot better than 67.

Andrew Landry -- all 5 feet, 7 inches and 150 pounds of him -- beat them all and finished with the best opening U.S. Open round ever at Oakmont.

Can someone who has never finished in the top 40 of a tour event actually win the first major in which he competes?

"Sure he can," said McMakin of Arkansas, where Landry was a three-time All-American. "Andrew is the kind of kid who doesn't care if he's playing in the U.S. Open or the Web.com Tour or a $10 game with his buddies. He doesn't know he's at the U.S. Open. He doesn't care. If he continues to keep it in the fairway, yes, he has a chance. He's so good with his short-iron distance control it's incredible."

Landry hit his approach shots tight enough to stand at 5 under after 13 holes and within range of Johnny Miller's record-setting 63 in 1973. He'd made three consecutive birdies before a second weather delay -- this one of nearly two and a half hours -- robbed him of his momentum. Landry missed a short birdie putt when play resumed, missed from medium range on the following hole, and then suffered his only two bogeys of the day before recovering with a brilliant approach on the brutal 477-yard ninth, his final hole of the round.

His parents, Dwain and Patricia, made the wet and wild journey with Landry, as did his older brother Adam. During the second delay, Dwain told ESPN.com that he and his wife had made personal sacrifices to finance Andrew's pursuit of the big leagues. A courier for FedEx for 30 years, Dwain said the couple opened a lawn cutting business on the side after Andrew turned pro in 2009.

"I worked 10-11 hours a day at FedEx, and then cut grass on my off day and on weekends," Dwain said. "We pretty much worked seven days a week, and if we had to do it all over again, we'd do it a million times. You have to help your kid chase his dreams."

The dream started taking shape last year when Landry won in Cartagena, Colombia, his first victory on the Web.com Tour. "He FaceTimed us and actually started crying and telling us how much he appreciates everything we've done for him," Dwain said. "We teared up, too. I told him one day he'll have kids and he'll understand how proud he's made us feel."

Landry earned his PGA Tour card, missed his first five cuts this year, and then made five of the next six. He qualified for the U.S. Open out of the sectional in Memphis, where he also tied for 41st -- his best showing -- at the St. Jude Classic. Landry told McMakin that he felt good about his game entering Oakmont, felt good about the way he was striking the ball. McMakin first recruited Landry to Lamar University, and then to Arkansas (coach and player headed there after Andrew's freshman year), despite Andrew's lack of Division I size. The kid was 120 pounds when McMakin first saw him at Port Neches-Groves High School.

"I thought he was too short for college golf," the Arkansas coach said by phone. "But he hit it so straight and he was so competitive, that I had to look two years down the road with him. You could give Andrew one golf ball and he could play the whole tournament with it, and he just outworked everybody. He had the drive to overcome his size, and he put on some weight at Arkansas and got longer and longer, and now he moves it out there over 300 yards."

They nearly won the NCAA title together in 2009. The team final between Arkansas and Texas A&M came down to a match between Landry and Bronson Burgoon, who held a four-hole lead with five to play. Landry won four consecutive holes to square the match, making for breathless drama on the 18th hole.

Landry landed his drive in the fairway before a reeling Burgoon sent his wide right and into the deep rough. "I knew we were about to win the national championship," McMakin said. But Burgoon hit one of the most memorable shots in college golf history to within inches of the pin, and Landry failed to match his birdie.

"But the heart he showed in that comeback," his coach said, "is what makes him special."

Now Landry has a chance to win a national championship of an entirely different kind. He was one putt away from finishing Thursday, and he desperately wanted to stroke it before play was stopped. "We had a little bit of a wait there with a fellow competitor," Landry said. "I was trying to get it in."

But then the horn blew and that was that. During the maddening delays, Landry said he "just kind of kept to myself, went to the locker room, stayed by myself, talked to my caddie a bit, and turned my phone off. Had my phone off the whole time. It was good to just be by myself and take it all in."

It was a lot to take in for a golfer who hasn't closed out any round this year in the top 20. But the magnitude of it all didn't shake Landry's confidence. He told his father he would win the U.S. Open, and then he went to work trying to honor his word.

"He doesn't want to make the cut or be in the top 10," Dwain Landry said. "He wants to win." Andrew's dad said it was a blessing to watch his son outplay the big boys at Oakmont. A million miles removed from the Pea Patch, Father's Day arrived three days early.