HAVEN, Wis. -- Jason Day could not choke back the tears on the 72nd green of his first major championship, and to the uneducated eye this appeared to be the natural reaction of a golfer liberated from the burdens of the big names with a consistent talent for losing the big games.

But this is not your average 27-year-old star in a sport that taps into a talent pool defined by wealth and access and emerald fairways manicured just so. Jason Day doesn't come from a country club place where a bad day is one when the nanny or landscaper calls in sick, or when the holiday bonus comes in at six figures instead of seven.

The coach and caddie hugging Day after he won the PGA Championship, Colin Swatton, would say his player came from "the wrong side of the tracks" in Queensland, Australia. So Day wanted to take you, Mr. Upper Middle Class Golf Fan, to that side of the tracks so you could understand why he kept pawing at his crying eyes before finishing off the great Jordan Spieth.

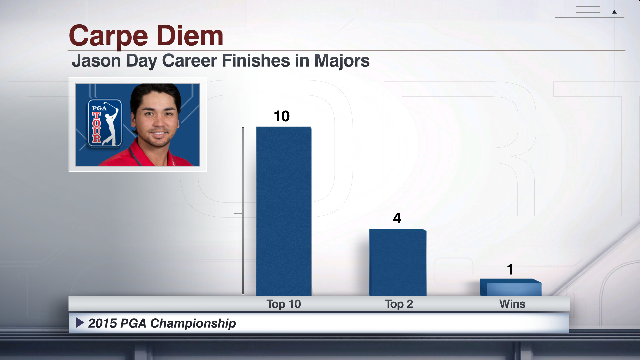

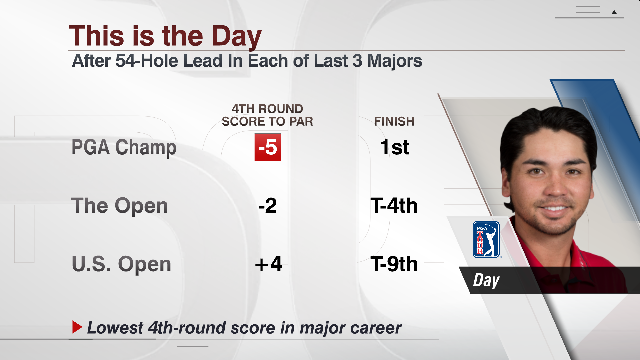

Day wanted you to know that the emotion wasn't about that putt he left short at St. Andrews, or his literal and figurative collapse at Chambers Bay, or the half-dozen top-fives in majors since 2011, even if he conceded that the near misses were starting to wear him down.

Day wanted to tell you that he was 12 when his old man died of stomach cancer, and that his mother needed to take out a second mortgage on the house and borrow money from his aunt and uncle to put him in a golf academy seven hours away. He wanted to tell you that he was getting into fights, and getting drunk at home before he was even a teenager. He wanted to tell you that his mother used a knife to cut the lawn because she couldn't afford to fix the mower, and that she'd heat up three or four kettles so her son could take a shower in a home that didn't have a hot water tank.

"That's why a lot of emotion came out on 18," Day said.

That's why this championship meant as much to him as any could mean to any athlete. Just as he held nothing back against the relentless Spieth, Day held nothing back in describing his journey from a lower-income, troubled child to a champion who would become the first man in golfing history to finish a major at 20 under par.

"If my dad didn't pass away," he said, "I don't think I would've been in a good spot. ... When a door closes, another door opens for that opportunity. ... I have no idea where I would be, what I would be doing. Probably wouldn't be doing much of anything."

So long before Jason Day conquered his demons and doubts at Whistling Straits, he was the ultimate money player. He'd explained last year -- when not many people outside a small circle of hard-core golf fans were listening -- that as much as he burned to someday supplant Tiger Woods as the world's greatest player, he wasn't consumed by the pursuit of trophies.

"I wanted to play for money," he said then, "because I never had it before."

Day has now banked close to $24 million in career PGA Tour earnings, roughly the equivalent of the combined winnings of Greg Norman, Jack Nicklaus, Arnold Palmer and Gary Player. So he has all the money he'll ever need, all the perks exclusive to the rich and famous.

Only he wasn't among those who showed up Sunday giving off a detached, privileged vibe. Day arrived at Whistling Straits with all the rage of that boy who arrived at Swatton's Kooralbyn International School, where he immediately engaged in a shouting match with his coach, and then channeled his anger toward his faraway dream.

Day wasn't the most talented prospect at the academy, not even close. "He just outworked everybody," Swatton said. "He just put in more hours than anybody else."

All these years later, a long way from Queensland, every ounce of Day's desire and work ethic was required to fend off a 22-year-old opponent from Texas who already has proved to be Ben Hogan tough. Spieth would shoot 4-under 68, finish at 17 under, and officially replace Rory McIlroy as the world's No. 1 player before a crowd Day said really "wanted him to win," and still Day beat him, and beat him handily.

Every time Spieth tried to apply pressure, Day repelled the attempt. He first extended his lead to 3 strokes with a birdie at the par-5 second, and then extended it to 4 at No. 7 by draining a monster putt that felt as if it was launched from the Lambeau Field parking lot 60 miles to the north, inspiring Day to pump his fists and scream.

"Every putt he made he was just so intense," said his pregnant wife, Ellie. "I kept saying he looks like an animal in some of those shots they got of him fist-pumping. You could just tell he was ready."

After making a bogey at the eighth, and then chunking his approach shot at the ninth, Day appeared to be ready to crack for the sake of old times. But he made a critical up-and-down par save after Spieth failed to do the same, establishing a tone for the back nine that the Masters and U.S. Open champ was powerless to change.

Spieth never cut the deficit to 2 strokes, never mind 1, on the closing nine; he couldn't create any momentum in the wake of his birdie at No. 10. On the 11th tee, with Day in the middle of his elaborate pre-shot, eyes-wide-shut visualization routine, a fan interrupted him with a warning about the wind. Day shot the man a look that could maim, if not kill, and then took it out on his golf ball with a 382-yard drive that brought Spieth to his knees.

Spieth lost all the bounce in his step when he headed down the fairway and realized how absurdly far Day had driven the ball. "Holy s---," Spieth yelled at the slugger. "You've got to be kidding me." Day playfully flexed his biceps in response, made birdie to regain his 4-stroke lead, and then finished off what he called the toughest round of his life.

Day crushed a 4-iron into the par-5 16th, glared at Swatton in how-do-you-like-me-now form, and punched the caddie in the shoulder. Resigned to his runner-up fate late in the round, Spieth seemed looser and more willing to engage his friend than he'd been on the early holes, where there was little meaningful conversation between them. When Day successfully lag putted on the 17th green to protect his 3-stroke lead, Spieth gave him an enthusiastic thumbs-up.

Of course he did.

Spieth served as Day's protector at the U.S. Open when the Australian collapsed after a sudden onset of vertigo, frightening even Swatton, who didn't see any of the usual warning signs.

"I thought honestly he'd had a heart attack," the caddie said. Spieth served as the de facto marshal of that scene, clearing people away from Day and barking at cameramen to restore some order.

Jordan Spieth does what Jordan Spieth does, and that's a good thing for the game of golf. But this wasn't a round shaped by Spieth's sportsmanship, or by the talent and determination that put him in position to win all of this year's majors. This was Jason's day, and Spieth had never seen him put on a clinic like this. In the scoring trailer, he turned to the winner and said, "There's nothing I could do."

Ellie Day said she saw "a whole shift" in her husband's approach the past few months, a period including the vertigo incident at Chambers Bay, the excruciating loss at The Open, and then the victory on the rebound at the Canadian Open. Ellie said Jason appeared more confident, more comfortable in his majorless skin.

"It just seemed like this was going to happen," she said after Sunday's trophy presentation was complete.

Jason Day had told people close to him that he wouldn't let what happened at St. Andrews happen to him at Whistling Straits. On the 18th tee, his lifelong ambition so close yet so far, Day told himself, "Don't double-bogey."

He didn't. He savored his walk with Swatton, the man he calls his second father, and dissolved into a puddle of tears with his final putt one precious foot from pay dirt.

His par beat Woods' major scoring record of 19 under (set at St. Andrews in 2000), and left him celebrating with his wife and 3-year-old son, Dash, a moment he started imagining when he read Woods' book, "How I Play Golf," as a teen. And before he left Whistling Straits, Day let everyone know something about the emotion that poured out of him and straight into Lake Michigan.

Those weren't the tears of major championship liberation. They belonged to a boy from the wrong side of the tracks who became a man a long way from home.