ST. ANDREWS, Scotland -- This is how it had to end for Tom Watson at The Open, chilled to the bone with the winds swirling and the descending darkness all but swallowing him whole on the 18th green. Forty years ago, as just another pro from the American heartland who had little interest in learning how to play links golf, Watson somehow won the Claret Jug as a clueless rookie with a piece of white heather zipped inside his bag.

A little girl had knocked on his door the morning of his Carnoustie playoff with Jack Newton, her Scottish brogue so thick that this son of Kansas City could barely understand her. She handed him the heather wrapped in foil as a good-luck charm.

"That's what golf is in Scotland, right there," Watson recalled Wednesday afternoon, and he said the same about this surreal scene Friday night at St. Andrews, where the Scots surrounded him as the 10 o'clock hour approached and reached out to make him one of theirs for the very last time.

"You're our hero, Tom," they shouted. "Thank you, Tom. Thank you for being a true champion."

Watson, 65, had shanked his second shot to the area in front of the green, and after his son and caddie, Michael, had pulled the pin with the putter in his father's hands, Watson barked, "Better hold it, son. These old eyes can't see it."

That drew laughter from the men, women and children huddled along the fairway railings, and in the balconies and grandstand seats above, before Watson went ahead and made the last bogey of his Open life. He waved his cap to the cheering crowd and bent forward to take a theatrical bow, and soon enough he was accepting congratulations from the freezing players who stuck around to witness history, the Matt Kuchars and Graeme McDowells, and falling into his wife's arms.

Watson would later tell the story of Bobby Jones winning the Grand Slam in 1930 and then showing up at the Old Course to play a friendly. Legend has it that the townsfolk heard that Jones was out there, and that thousands of them swarmed him as he completed his round.

"And when I was going up there just across the road," Watson said, "I think I had an inkling of what Bobby Jones probably felt when he walked up the 18th hole."

What ended at nightfall began under a restorative midafternoon sun. Rains had pounded St. Andrews and delayed the start of the second round 3 hours, 14 minutes, leaving Watson, Ernie Els and Brandt Snedeker in a race against time to give the old man his proper farewell.

Dressed in a turquoise sweater and matching glove, Watson kissed his wife Hilary and stepped onto the tee box at 4:39 p.m., nine minutes before his tee time, holding a signed and rolled-up Open flag behind his back. He presented it as a gift to Ivor Robson, and then spoke for five minutes with the retiring starter under the cover of his big blue umbrella, legend to legend.

Watson hit his tee ball first to start his 128th and final Open round, watched Els and Snedeker hit theirs, and then basked in the standing ovation as he walked down the first fairway with his son Michael on the bag. "Scotland and Kansas City love Tom Watson" read a sign held by a couple of fans, including one wearing a Royals jersey. The fans behind the green stood for Watson after he bladed his approach shot long, and despite his three-putt bogey, the crowd near the second tee granted him his third standing O of the day.

Watson ripped into his drive at No. 2 and immediately looked skyward and waved at the passing seagull that he'd nearly clipped, telling his son, "That was close."

No matter his score on this day, Watson would do his damnedest to ensure this remained a good walk unspoiled.

What a long, strange trip these four decades had been. A man who preferred keeping his ball in the air, Watson detested the vile bounces and whims of ground-game golf in the early years, even as he was winning one, two, three Opens at Carnoustie, Turnberry, and Muirfield. It all changed in 1981 during a casual, 36-hole day at Royal Dornoch with his friend Sandy Tatum, the former USGA elder. They'd played on a clear, windless morning before retiring to the clubhouse for a few pints as the skies suddenly turned ugly.

Watson studied the howling, sideways rain from his room-temperature sanctuary before shooting his friend a mischievous look.

"Tatum," he said, "what do you think?" Nothing more needed to be said. Tatum rounded up the caddies, and the Americans marched out there and played like true Scotsmen.

"That's when I fell in love with links golf," Watson said.

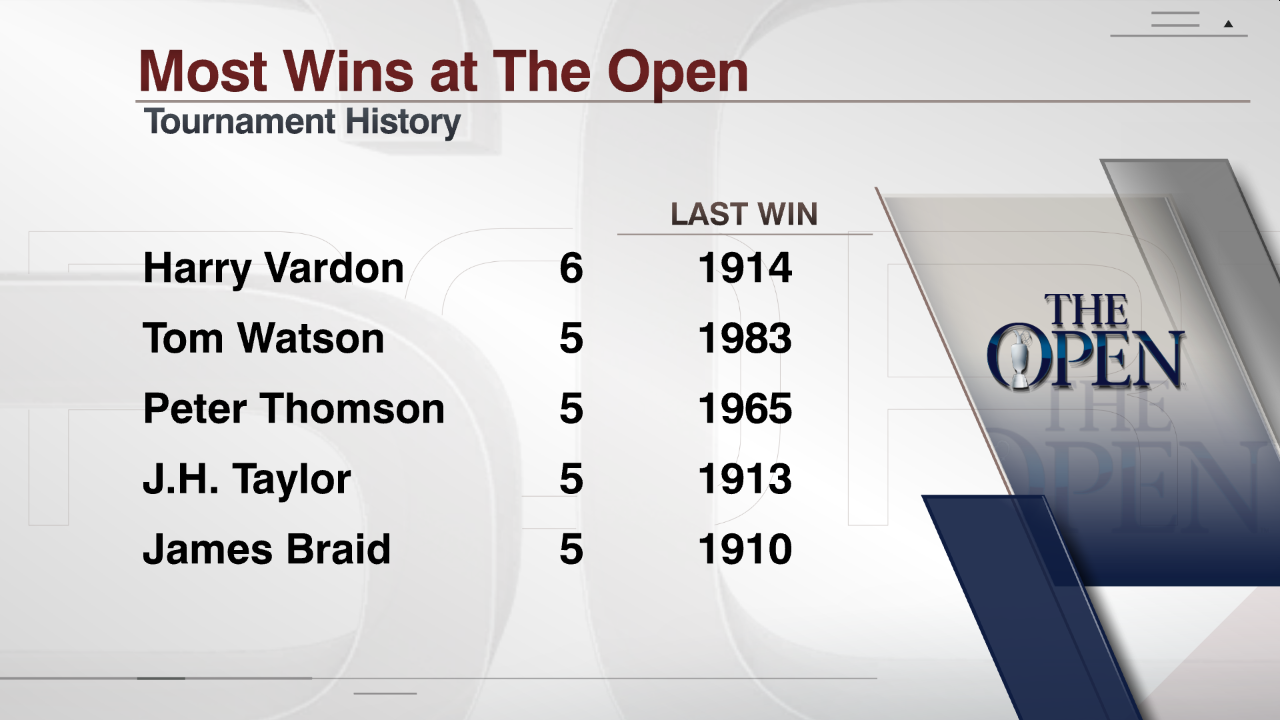

He won The Open the following year, and the year after that, too. In 1984, Watson blew a three-peat and a chance to match Harry Vardon's record of six Open titles when he hit a shot off an uphill lie on the Road Hole 30 yards to the right of his target, making an Old Course winner of Seve Ballesteros.

Watson saw a lot more good bounces than bad ones in his day, but a really bad one in 2009 cost him a starring role in what would've been the greatest golf story ever told. More than a quarter century after his last Open victory, and mere weeks before his 60th birthday, Watson was one par from the fairway away from winning again at Turnberry, the place where he proved to himself in 1977 that he could beat the best. He'd defeated Jack Nicklaus there in an epic test of wills, and now he was about to top that feat while Nicklaus watched from his Florida home.

Watson hit a perfect eight-iron toward the green, and millions of heartbroken viewers know what happened next. The ball landed on a down slope and ran long, Watson couldn't get up and down with his putter and Stewart Cink won their playoff. Nicklaus and his wife Barbara cried on their couch, according to Joe Posnanski's defining book on the Watson-Nicklaus rivalry, "The Secret of Golf," and Watson walked into the interview room and made sure the gutted storytellers in the media didn't do the same.

"This ain't a funeral, you know?" he said to a burst of laughter.

Six years later at St. Andrews, Watson wouldn't let himself cry the way he had while joining Nicklaus for his final round in 2005. Watson called retirement for a champion athlete "a little bit like death," but said his only regret was knowing he could no longer hit it long enough and straight enough to compete with the kids from the Old Course to Augusta National, where he will play the Masters next April for the last time.

Branded in his youth as something of a choker, Watson closed his career with eight major titles, one ahead of Arnold Palmer, Gene Sarazen and Sam Snead. He ended up winning 39 PGA Tour events, tormenting Nicklaus on the back nine of the Golden Bear's prime and accomplishing enough titanic things as a player to reduce last year's disastrous turn as Ryder Cup captain to a footnote that's already fading to black.

He had nothing left to do as an active golfer. Nothing except saying goodbye.

When Watson reached the 17th tee, there seemed no way he could possibly avoid a postponement of play and an anticlimactic finish early Saturday morn. "But somehow," Snedeker said, "by the grace of the golfing gods there was a little bit of sunshine there at the end, so we could get those last two holes in."

It wasn't sunshine as much as it was the distant glow of lights from those familiar Old Course buildings. And it wasn't the grace of the golfing gods as much as it was the grace of Thomas Sturges Watson, who told Snedeker and Els to make the call on No. 17.

"Tom was very encouraging to me and Ernie all day, trying to keep us in the tournament," Snedeker said. "He asked us all day if we wanted to finish, not finish. He kept saying, 'Great putts, keep fighting guys, you're right there.' He was very much a great playing partner today. It was not about him at all, and I wouldn't expect anything else."

So Snedeker and Els agreed that they should get Watson safely to the house, even if they could barely see their golf balls and the cups they were aiming at. Snedeker double bogeyed the 17th in a rush, killing his chance to make the cut, and when it was over he acted like he didn't give a damn.

Tom Watson, his idol, struck his final drive at 9:44 p.m., and then summoned his fellow players and their caddies for photos on the Swilcan Bridge. Soon it was Watson posing with Michael, and then Watson alone with his arms thrown wide in touchdown form.

"It was unlike anything I've ever witnessed," Snedeker said.

On the bridge, the 34-year-old pro from Nashville told his idol, "We're getting the hell out of your way. This is your moment. Thanks for the memories."

Watson missed some irrelevant putts on No. 18 and signed for his 80, and then did his last round of interviews while his 32-year-old son guarded the bag outside. Tom had told Michael down the stretch that he shouldn't cry, that this was a time of unmitigated joy.

Michael fought off the tears, barely, while watching his father take in all that love from the fans. "This is the first time I think the emotions got the better of him," Michael said. "I haven't seen that before, but you know what? It's all right."

As the son and caddie spoke near the scoring trailer, dangerous winds picked up and started knocking around railings and posted signs, a reminder of the weather Watson sometimes had to confront while winning four of his five Open titles in Scotland.

Truth is Watson started out as a soft and comfortable American golfer and left this country as another William Wallace.

"It's been one hell of a run," he said.

It ended the way it should've ended for the greatest links player the United States ever produced -- in the raw, gathering darkness, with a crowd of hearty Scots thanking their champion for sticking it out over 40 glorious years.