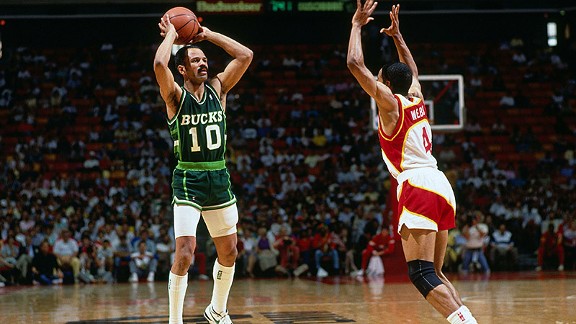

Scott Cunningham/NBAE/Getty Images

Scott Cunningham/NBAE/Getty ImagesAmong John Lucas' most enigmatic moments? A free throw attempt with his eyes wide shut.Renee Richards was sitting front row the night her doubles partner, John Lucas, put on a show at Madison Square Garden.

As Richards recalls, the Milwaukee Bucks are blowing out the New York Knicks. It’s “an exhibition like you wouldn’t believe,” she says.

The 33-year-old Bucks point guard is running up and down the court screaming “No way, no way,” and in the closing moments he does something outrageous.

“He’s right in front of the basket where we have our seats, and he stands there at the free throw line and he yells, 'No way Renee, No way Renee,'" she said. "And he closes his eyes and he makes the free throw.”

It's a quintessential Lucas performance, but to Renee it was so much more.

Lucas was a two-sport prodigy. He landed on Sports Illustrated’s “Faces in the Crowd” as a 14-year-old tennis phenom, topped Pete Maravich’s scoring record in high school and was an All-American in both sports at the University of Maryland. Lucas was selected first overall by the Houston Rockets in the 1976 NBA draft -- a rare feat for a point guard. Three days later, he was signed by the San Francisco Golden Gaters to play World Team Tennis -- a rarer feat for a point guard.

Richards, now a practicing ophthalmologist, was the transsexual tennis player who stirred international controversy after the former Richard Raskind appeared in tournaments as a 41-year-old woman. The United States Tennis Association barred Richards from competing in the 1976 US Open but Richards challenged the USTA in New York State Supreme Court, which ruled she could enter the tournament without submitting to chromosome testing. In 1977, she played in her first US Open as a woman. A spectacle ensued.

The next summer, Richards joined forces with Lucas on the New Orleans Nets. An NBA point guard and a 43-year-old transsexual -- both lefties -- playing mixed doubles.

“It was like being at the wedding of a transvestite and a dock worker,” quipped one reporter after watching them at the 1978 US Open.

Lucas, who says the pairing went 28-1, saw it differently: “We were two lefties that both hit sliced serves. Our height was very good and we created problems.”

The Lucas-Richards duo was perfect for the quirky but competitive World Team Tennis. They did things -- chest bumps, for instance -- that would have been frowned upon in other tennis venues.

“I put a basketball game on a tennis court,” Lucas said. “That’s how I played tennis. I tried to make it an athletic event.”

Off the court they were partners in mischief. Richards recalled a road trip in Indianapolis when they were in a weight room and some men started making offensive remarks about her sex change. Lucas, protective of Richards, threatened them with a 200-pound barbell.

“And he says ‘Listen, Dr. Richards is my friend and she’s my doubles partner. I don’t want you to say anything more against her,’” Richards said, laughing. “And this guy just looked up at him and John’s holding this 200-pound weight over his head, and that was the end of that.”

Richards mentioned another time when Lucas walked into a redneck bar in Lakeland, Fla., and asked for a six-pack of Heineken.

“A black guy in Lakeland, Fla., in the middle of the night in this hot, scalding road house, the door won’t open, the neon light in front of it and guys playing pool inside, not a black guy in sight. I said, ‘You’re not going in there,’" Richards said.

Lucas didn’t listen. He walked in, asked for the beer, and the bartender froze; he couldn’t comply since the customers were watching, but he couldn’t outright ignore the request. Richards broke the silence, asking the bartender for the six-pack. The bartender gave it to her. Problem solved.

“He was very naïve in some ways but brilliant and sophisticated and educated and all that, but in some respects he was a kid,” Richards said.

Renee Richards’ notoriety was fading when she joined John Lucas on the Nets. One year removed from the saga of the 1977 New York Supreme Court ruling, she was gaining recognition on the pro tennis circuit as a competitor, not a sideshow attraction.

Lucas, meanwhile, was starting to lose control of his life. Drug problems surfaced after he was sent to Golden State in 1978. In his third and final season with the Warriors, he missed three team flights, six games and more than a dozen practices. Whisperers around the league said cocaine was the problem. Golden State, then in postseason contention, suspended Lucas for the final eight games of the season.

Jack McCallum profiled Lucas the following offseason in a 1981 Sports Illustrated story titled “Picking Up The Pieces.” Lucas’ psychiatrist, Dr. Robert Strange, said the troubled point guard was “emotionally and physiologically fit to continue his profession.” Depression, not drugs, was thought to be the cause of his problems.

“It’s just an unfortunate accident that happened to a good guy. I’m not a bad guy. I’m nobody’s problem child. Never have been, never will be,” Lucas told McCallum.

The Warriors shipped Lucas to the Washington Bullets for two second-round picks that summer and the problems escalated. Donald Dell, then Lucas’ attorney, said his client approached him about hiring a personal security guard to fend off drug dealers. So Dell arranged for a former D.C. policeman to trail the NBA star.

“And guess what?” Dell said. “It was not successful. After a couple months, somehow people would always still get drugs to him, even though this guy was traveling with him and living with him in his apartment.”

The Bullets waived their problem child in 1983, but in spite of the off-court antics, other teams could not resist the talented point guard. Lucas -- after a brief tennis stint -- joined the Lancaster Lightning of the Continental Basketball Association. A 20-point, 14-assist performance, in one half, caught the attention of San Antonio Spurs general manager Bob Bass, who signed Lucas for the remainder of the 1983-84 season.

San Antonio traded Lucas to Houston, where he played alongside Hakeem Olajuwon and 7-foot-4 Ralph Sampson on the greatest team that never was. He failed a drug test that December and “retired,” but completed a 40-day rehab program and returned to the court that season.

The next year with the Rockets, Lucas averaged 15.5 points and 8.8 assists through 65 games. But his season was cut short when on March 11, 1986, he awoke from a cocaine-induced blackout in downtown Houston. Instead of trying to make it to practice, he took more cocaine. He was released after failing a drug test a few days later.

The Rockets reached the Finals sans their starting point guard, losing to the Boston Celtics in six games.

The drug relapse in Houston turned out to be Lucas’ last. Months later, he launched a substance recovery program which has evolved into a network of drug treatment centers for athletes. Today, he has a cult following as a training guru and life coach. Recent pupils include ex-Rutgers coach Mike Rice, Kentucky assistant Rod Strickland and NFL rookie Tyrann Mathieu.

The blind free throw happened in 1987, a year after he was cut from Houston. The Milwaukee Bucks signed him midseason and he averaged a career-high 17.5 points playing under Don Nelson.

That night, in his 12th game with Milwaukee, Lucas records 27 points, seven rebounds, eight assists and seven steals in a 127-104 win over New York. He sits out much of the fourth quarter, but subs back in with four minutes remaining and the Bucks leading 110-94. In his first possession, he sinks a jumper over Gerald Henderson. A couple of minutes later, he is sent to the foul line and hits the first of two freebies.

The second one, the blind free throw, doesn’t go exactly how Richards remembers. Before the shot, Lucas smiles, glances at his doubles partner -- who he hasn’t seen since 1978 -- and shouts “No way.” But if he closes his eyes, it’s barely noticeable. It’s only for a split second.

The shot goes in, he backpedals, and hustles through the 48th minute. He’s prancing around like he’s a rookie, MSG Network announcer Greg Gumbel says.

The Bucks have last possession and they’re running out the clock. An unguarded Lucas is standing in the paint, calling for the ball. Forward Junior Bridgeman finds the slick lefty, who converts a mid-air, catch-and-shoot just after time expires, and disappears under the stands.

Renee hasn’t seen him since.