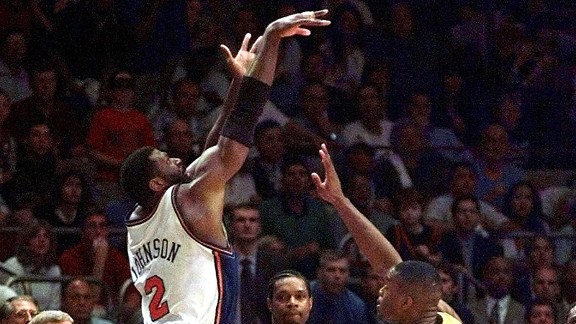

AP Photo/Ron Frehm

AP Photo/Ron FrehmShots like Larry Johnson's improbable 4-point play in the 1999 postseason transcend the game.

I didn’t know Larry Johnson’s 4-point play was shady, for it brought only joy to my house. There was no social media to alert us to how Antonio Davis barely touched Johnson, and broadcaster Bill Walton’s musings about a “phantom foul” were drowned out by a father and son, celebrating in unison.

It was glorious because the Pacers were Evil and the Knicks were Good. My dad was a New Yorker, transplanted to San Diego. I didn’t know the first thing about New York, but I knew we got along during those brief moments when the Knicks grazed glory. We high-fived and hugged, and I did a backyard victory lap that ended in some leaping on the trampoline. Back injuries might have robbed Larry Johnson of his hops, but his second life as an outside shooter propelled me skyward.

Legend has it that sports strengthen the bond between father and son. Sometimes, for some of us, sports are the bond itself. My father was divorced, bitter, paranoid and clinically depressed. A dank fog hung over his house in sunny Pacific Beach. The lights were dim, the carpet was dirty with termite droppings. Cobwebs would form in corners of the living room, especially during those long periods when my dad couldn’t bring himself to rise from a cruddy 1970s-era waterbed.

He wasn’t a bad person, but he wanted no part of happiness. And he compounded that problem by pushing those close to him away by trying to pull them closer to his misery. Knicks fandom came to suit him quite well, especially during the Isiah Thomas years.

Though the Knicks were powerless against Michael Jordan, they had the unique power to chase away my dad’s demons. The games made him present, animated, even cheerful. With his curly hair, glasses and goofy grin, he looked like an ideal sitcom dad -- the kind who casually strolls into his moody kid’s room and corrects the young man’s perspective with a joke here, an anecdote there.

He even found joy in the pain of Reggie Miller’s incandescent shooting. My dad was so taken with Miller’s takeover moments that he’d lose track of how the Knicks were losing, shouting “wow!” for situations that begged for curse words. Our house was enlivened by such tragic basketball figures as Patrick Ewing, John Starks and, finally, LJ.

Many will remember Larry Johnson’s famous shot for his goofily miming “LJ” with his arms, at the height of glory. Others recall how the entry pass was almost stolen before Johnson snagged it. A smaller subset may remember Johnson blessing sideline reporter Jim Gray in Arabic after the game. What stuck with me, what will always stick with me, is the special way Madison Square Garden reacted. Later that night, in a highlight montage of the shot, I saw the most awe-striking crowd reaction I’ve taken in on television, short of ordinary folks revolting against a despot. To know why is also to know how the game has changed.

Down three with 11.9 seconds left and lacking any timeouts, the Knicks were doomed. In 1999, 3-pointers didn’t just fall from the sky. Well, maybe all 3-pointers actually do fall from the sky, but back then, they just didn’t rain reliably. New York made 382 3s in 1997-98, matching what the 2012-13 Grizzlies did as last season's last-place team in 3s made. It wasn’t that the Knicks were especially bad from distance, as they were actually top-10 in made 3-pointers in their last full season before the 1998 lockout. Iso-era teams just lacked shooters, or at least the inclination to let it fly. Unless your team had Reggie Miller, the Grim Reaper was pretty much your sixth man in these kinds of situations.

That’s perhaps why the Knicks crowd is sitting up until the point when Johnson ties the game. Standing represents anticipation. Sitting equals resignation. Fans weren’t braced for the Knicks' cramming one of their four 3-pointers a game into the last, heavily guarded 12 seconds of action. Notice that Miami Heat fans -- those who had not already left the arena, anyway -- are standing to watch Ray Allen try a game-tying 3 in Game 6 of the 2013 NBA Finals. A hopeful crowd is certainly braced for the possibility that one of the Heat’s many marksmen will come through. Miami’s arena hops in celebration, but it looks nothing like the human storm surge of 18,000 in Madison Square Garden, compelled from seated to a simultaneous high-jump by the unlikelihood of a 3-pointer combined with the even zanier unlikelihood of a 4-point play.

“It still sends chills up and down my back when I see it,” Jeff Van Gundy, then the Knicks' head coach, would later say of the crowd reaction. WFAN radio host Joe Benigno described what happened as, “The entire crowd just came up as one.”

That night, I fell in love with the pixelized image of Madison Square Garden, which looked like the world’s easiest game of Whack-A-Mole. My dad was a divorced, angry loser. I was a nerdy, brace-faced loser. Our social calendars might as well have read, “Whenever it snows in Pacific Beach.” He’d often drive around, just to drive around, muttering vitriolic nothings at the air. I’d pass the hours by throwing a penny at a waggling pen, smacking it over the fence of a baseball stadium I’d constructed from encyclopedias. Yet two social failures were able to share kinetic euphoria with thousands, jumping as they jumped, clumsily hugging as they clumsily hugged. Perhaps it’s pathetic that this nearly comprised our bonding with each other and with the outside world, but it was better than nothing.

I can’t remember what happened the next day, and that’s what’s so great about Larry Johnson’s shot. The next day was probably dull and terrible. And the next day. And the next one after that. Wonderful memories of June 5, 1999, dwarf so many negative months, the quick adrenaline spike of joy winning storage precedence over the long ebb of misery.

Since then, I’ve wondered if I write about basketball because I’m chasing that transcendent Madison Square Garden moment of an 18,000-person nirvana, or because I’m retreating to the few times I actually shared with my father. It’s all been a search for connection, one way or another. It’s all been an escape, too.

The games are trivial and the players are strangers to the fans who live vicariously through their exploits. This ridiculous game’s redemption lies in how it foments a bond between those strangers. Fans from disparate backgrounds can understand what it’s like to feel the exact same thing at the exact same time. A wonderful sense of community can form under the MSG lights. A broken family relationship can look like what each side always wanted, under the warm glow of the TV. In a perfect world, we wouldn’t need sports to serve as a proxy for relationships. But the world will never be as perfect as the feeling of seeing Larry Johnson hit that shot.