Getty Images

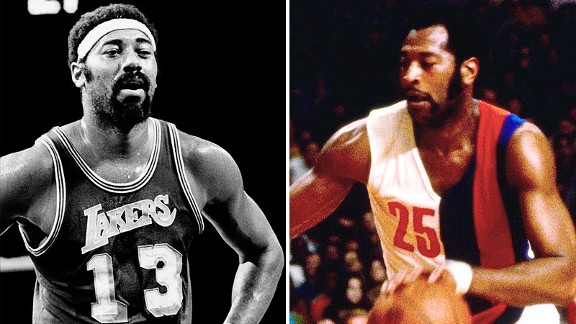

Getty ImagesThere's no visual evidence, but Wilt Chamberlain's block of Gus Johnson's dunk is the stuff of legends.

The moment doesn't exist in photo or film, but surely it does exist.

The Baltimore Sun on Nov. 26, 1966, recounted the powerful blow the day after it occurred, in a 129-115 victory by Chamberlain's Philadelphia 76ers over Johnson's Baltimore Bullets in Baltimore. Johnson, according to the paper, suffered a “wrenched shoulder” thanks to Chamberlain's mammoth swat.

The Los Angeles Times on Feb. 26, 1981, recalled that Wilt Chamberlain “dislocated the shoulder of the powerful Gus Johnson when he blocked one of Gus' dunks.”

The Philadelphia Inquirer on Oct. 26, 1986, got the scoop from Billy Cunningham, who witnessed the event: "It was Gus against Wilt," Cunningham said. "Gus went in to dunk, and Wilt caught the ball, threw Gus to the floor, and they had to take Gus off the floor with a dislocated shoulder."

Imagine if this kind of debilitating block was registered in the YouTube age. It'd be plastered into our digital minds and never forgotten. Instead it occurred in an era when players were supposedly plodding, slow, uncoordinated or some combination of the three. And if you possessed some measure of athleticism you were unfairly taking advantage of the physically unfortunate. Rare is the footage to combat these prevailing myths.

Those misconceptions don't reconcile with the image of Wilt Chamberlain, a 7-foot-1 center who jumped high enough to block shots at the top of the backboard's square. They also don't quite jibe with Gus Johnson, a 6-6 forward who shattered three backboards with his monstrous dunks in the 1960s.

One such instance in 1964 caused Hawks guard Sihugo “Si” Green a bit of discomfort:

Gus Johnson remembers being "about three steps in front of Lenny Wilkens, Chico Vaughn and maybe Cliff Hagan," accepting a crisp, one-bounce pass from Wali Jones and going up to dunk.

[...]

"I hit the rim with my forearm, just tore the basket down," Johnson recalled. "The rim came down on Sihugo Green's foot, and he missed two weeks.”

Wilt and Gus exemplified the seemingly impossible possibilities of human athleticism, but they weren't alone. Elgin Baylor of the Los Angeles Lakers was already side-stepping opponents on the fast break with a move that would later be dubbed the “Euro Step.” Dave Bing of the Detroit Pistons was spinning defenders in circles with his tricky handles. Walt Bellamy of the Chicago Packers could cut baseline and deliver a gliding reverse slam despite being a 6-11 center.

By the early 1970s, guards like 6-3 Randy Smith were dunking with artistry that we're now fully accustomed to.

But Gus Johnson's and Wilt Chamberlain's cataclysmic clash remains something of a Holy Grail for the era's athleticism. Words and recollections attest to its power, but it will never really be found again. Even more curious is that Wilt and Gus reveal to us the fleeting nature of athleticism and its deceitful promise of eternal miracles.

Johnson was tragically like a Greek hero. His mythical feats became fewer and harder to find as his career progressed. Yes, he possessed a muscular physique like Hercules, but knee ligaments, unlike muscles, can't be chiseled like marble. Knee ailments knocked out large chunks of his career and limited his court time. Unfortunately, the hobbled hero can't recount his glory days to us anymore. He passed away far too early in 1987 due to a brain tumor.

Wilt Chamberlain's mythological countenance endured for his whole career. More than any single player he extended the limits of what was physically and conceivably possible. In addition to basketball, Wilt had run marathons, pumped more iron than Arnold Schwarzenegger, and even became a volleyball Hall of Famer. In 1999, though, the one muscle that can ill-afford to weaken gave out on Wilt. The Big Dipper's heart stopped beating and the titan of years gone by passed away quietly in his bed.

As today's star athletes eventually reach their old age, they can point back not only to words and memories, but the indisputable video to prove just how awesome, just how spectacular, they were. The men of the 1960s can't always provide the film, but, in an odd twist, the lack of film aggrandizes their accomplishments.

We can see exactly how LeBron James delivers his machine of flying death. In fact, we can see it in real time, slow motion, from cameras behind the backboard, from cameramen camped at the baseline and numerous other assortments of angles and speeds. The saturation of media today perhaps peels away too much mystique of our current hardwood immortals.

But for the titanic block that Chamberlain delivered on Johnson, we have a few words and our imaginations to work with. That's something we decreasingly get to use these days. We know not what type of dunk Johnson was attempting. We don't know exactly how Wilt's body was positioned. We're oblivious to how far out Gus leaped to instigate the showdown. We're at a loss for the look on Chamberlain's face as he successfully protected the rim or, conversely, the pain on Gus' face as his shoulder separated.

What we do know teases us and propels us to fill in the gaps with our imaginations. Every man and woman can hear the story, but play it out in their own individual way giving the moment a unique personal power. The cold and calculating camera robs us of that private vision. The void of knowledge, the scarcity of detail, the sketches of what was, breathe life to a real moment that will forever be a tall tale.