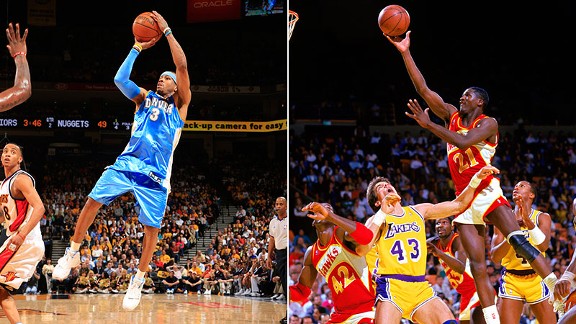

Rocky Widner/NBAE/Getty Images and Rick Stewart/Getty Images

Rocky Widner/NBAE/Getty Images and Rick Stewart/Getty ImagesThere once was a time when dozens of players had gaudy scoring averages.

Brent Barry e-mailed. He was wondering why these days so few NBA players average 20 or more points per game.

There's just nine in the whole league, at the moment, he pointed out. As recently as 2007-2008 there were 27.

Three times as many!

Remember, those are the most exciting players to watch. The human highlight reels, the putting-butts-in-seats guys, the players a million kids on a million blacktops dream of becoming.

And two-thirds of them have essentially gone missing. As if stolen.

Gone with them are a bundle of special memories, including almost all the 50-point nights.

If aliens had lured them to another planet to start a highly rated hoops league there, we'd have a massive story worthy of Hollywood.

But they have disappeared in some other way that's tougher to notice. Slipped out the back door. And ... crickets. Our scorers have gone, our scorers have gone and ... barely a whisper.

What is going on?

Barry had some theories:

Playing-time cutbacks?

Lots of injured stars this season?

Teams playing at a slower pace?

This was serious. I fetched a legal pad and scribbled down those theories, and added some of my own:

Scoring down in general?

Top players shooting less by choice in the name of efficiency? (The highest salaries that used to go just to the highest points-per-game guys now tilt to those with the best scoring efficiency.)

More stars saving early-season energy for the playoffs?

Coaches giving more big minutes to elite defenders, which would both keep more shooters on the bench and make opposing scorers less effective?

Better team defense? The effective kind of rotating/switching defense that was an outlier for the Celtics in 2008 is now commonplace, which could make scorers less effective while also making those would-be big scorers more tired from running around so much?

Scoring

Scoring is down, a little. A typical NBA team so far this season has scored about 98 points per game. That number was 99.9 in 2007-08, and a whopping 109.9 in 1986-87. It's part of the story, but it's not the whole thing.

Minutes

Just about a year ago exactly I did some rough-and-ready research and found that teams whose top players play a ton of minutes don't win NBA titles. Not anymore. They used to. But not in recent years.

The best theory I heard to explain that came from David Thorpe, who laid the blame it on that hustling, switching team defense. Once upon a time, lots of teams preferred an "isolation" offense, which meant one player dribbling alone against one defender, while as many as eight guys caught breathers. On many NBA plays these days, nobody stands around. It's common to see 10 guys flying all over the court. This is not your daddy's NBA. It's great for fans and team play, but it's much tougher for players: A minute of play, the theory goes, is now much more work than it used to be, and one result is that more rest is required.

I went into this season expecting that more smart teams would limit their top players' minutes, Popovich-style, not because they are weak in the mind nor because they are not in good-enough shape. But because it works.

Basketball-Reference was built to answer these kinds of questions, and what I found was that while some top teams may be managing minutes, plenty are not. I dug in, using the top 10 players in minutes played as a test. In the first 36 games of the 2007-08 season, the 10 players with the most minutes played logged a combined 14,281 minutes. This season, that list includes Kevin Durant, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, Stephen Curry and Damian Lillard, and the total minutes they have played is down to 13,793. So maybe that's having some effect.

And while there are plenty of heavy-minute players this season, some of those on limited diets of playing time, because of injury or strategy, are players who might have scored more in a different season. Brook Lopez, Tim Duncan, Jamal Crawford, Kevin Martin, Kevin Garnett and Derrick Rose are among those who'd threaten the 20-per-game with a typical alpha-scorer's playing time.

But it's not some massive historical trend that big names are sitting more. I checked 1985-86, too, back when Dominique Wilkins and Larry Bird were scoring at will, and in that season the top 10 combined to play even fewer minutes than today's big names.

Joe Johnson is something of a poster child here: He was scoring 21.7 points per game five years ago playing the second-most minutes in the league. This year he's playing less and scoring just 17.1 points per game. In other words, Johnson is one of the players Barry was e-mailing about, one of the players who has been affected by ... whatever is happening.

Did they rob us of this transcendent scorer by sitting him? Not exactly.

His minutes are down, but his scoring is down even more -- even with his old minutes, he'd only score 18.5 points per game at this season's scoring rate. That's the trend: There are plenty of gifted scorers playing the kinds of minutes that used to get you 20 points per game. Those players just aren't scoring as much now.

Something else is up.

Pace

Maybe the game has slowed down? It would explain a lot. Simply keeping the ball longer before shooting would explain now the same number of minutes played would result in fewer possessions, fewer shots and, importantly ... fewer points.

It's so perfect!

But it's not happening. The average pace has bounced around this season but is just a tad slower than five years ago, at 91.7 compared to 92.4.

Shot selection

OK, so teams are playing at the same speed, and the high-minute players are playing about as many minutes as ever.

Maybe they're just shooting less? Maybe stat geekery has inspired some kind of revolution in thinking, and suddenly all those inefficient gunners are thinking twice about jacking up bad shots?

Despite the lack of total points, top players do have slightly better field goal percentage (46.7 compared to 45.7 percent) this year compared to five years ago.

Again using the the players who lead the league in minutes this season as a sample group of the kinds of players who are candidates to average 20 or more points per game, we find ... this theory strikes out too. The truth is, they're shooting more often.

This year those top players are taking a shot every 2:19 of play, compared to every 2:24 five years ago. (In 1985-1986 they shot every 2:10, which is a lot of shooting.)

I had been abusing the numbers of Basketball-Reference for some time, but they simply would not give up the answers I was looking for.

Time for another perspective.

As soon as I explained the issue to Thorpe, he declared "I know exactly what's going on."

The defense.

Thorpe explains it best in the video, but the gist is this: In recent years more and more NBA coaches have signed up for the defensive philosophy, popularized by Tom Thibodeau since 2007-08, of "flooding ball-side box."

This is not the same as double-teaming, but it has some similarities. When the ball is on one side of the court, watch for this: Very often an extra defender sneaks over to join the action, bringing a crowd of defenders closer to the ball. It's something that became legal when the NBA began allowing zone defenses in 2001, but it took until 2008 for coaches to really figure out how to take best advantage.

That's when the big-time gunners started to disappear.

Flooding the side of the court with the ball makes everything tougher for that star scorer, starting when he makes the catch and assesses options. Driving lanes are tighter or closed off entirely. More defenders have more ability to get hands in faces. It's difficult to reach favored spots on the court, and to operate once there. These are the times that try virtuoso's souls.

And when there's an extra defender on one side of the court, the good play is pretty obvious: pass to the other side, where your team has the numbers advantage.

If Thorpe is right, that this team defensive technique is to blame for our new shortage of big scorers, there are various ways you might expect the data to have his back. For instance, secondary scorers -- those guys catching the ball on the sparsely defended weak side -- ought to be scoring more, while top players could expect to see an uptick in assists.

That's all happening. Stars putting up big numbers are incredibly hard to find this season compared to five years ago, but overall team scoring is down only about two points per game -- the non-star scorers must be picking up a little slack.

And as for assists, in 1985-86, the 10 players who played the longest minutes in the season's first 36 games combined for 1,308 assists. Five years ago, that number was 1,482. This year it's all the way up to 1,768.

Not getting to the line

There's one other part of this story. A big part. And it's this: Free throws are more rare than ever. There are 22.3 per game on average this season, which is the lowest level in NBA history. And it's not a one-year aberration. The second lowest year ever was last year. Every season since 2008-09 is in the top 10 all-time for fewest free throws.

Now we're getting somewhere.

Top players are simply not getting to the line.

Those high-minute players combined to shoot more than 2,400 free throws in the first 36 games of both 1985-86 and 2007-08. This season, they stepped to the line just 1,757 times.

In a way, this is one mystery solved. Pace mildly slower. Minutes slightly lower. Scoring generally down a bit. Free throws are down hugely compared to all of history and 10 percent over the last five years. New defenses can explain some or all of that, and it's more clear than ever why so few players are averaging 20 points per game.

But this mystery comes with a sequel: Why so few free throws?

One theory is that the NBA has reduced some of the referee trickery available to big scorers, for instance, by discouraging the "rip-through" move which led to cheap free throws for top scorers. Refereeing oversight has evolved, too, with the league looking over referees' shoulders more than ever in the name of a consistently called game. Perhaps "star calls" are on the wane generally.

Another possible explanation, however, is that Thorpe's defensive theory explains this too: with extra defenders around, perhaps players simply aren't attacking the rim, where big numbers of fouls are drawn, as often as they used to.

If so, that could be a major factor -- the major factor, even -- in explaining why top players aren't scoring like they used to.