|

When Sandy Alderson became general manager of the Oakland A’s, he enlisted the analytical help of Eric Walker, a Bronx Science and RPI graduate. Walker was influential in the analytical theories espoused by Alderson and then Billy Beane with Oakland. Although the two haven’t remained in contact in recent years, Walker discusses the baseball philosophies Alderson developed in the 1980s with his influence.

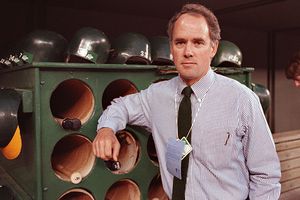

AP photo/Rusty KennedySandy Alderson, who started as a corporate lawyer for the Oakland Athletics and became GM, is shown in the Athletics dugout at Cincinnati's Riverfront Stadium on Oct. 18, 1990, before the start of Game 2 of the World Series.

How did you and Sandy Alderson first become acquainted and establish a professional relationship? I had become aware of and interested in baseball analysis through Earnshaw Cook's first book, “Percentage Baseball” (that is a story in itself). Going on from that, I had developed thoughts, principles and metrics of my own. I was originally focused on the Giants simply because I lived in San Francisco at the time. After a several-seasons-long campaign of persuasion, I finally got the Giants to take me on. That relation didn't last too long, because they never really did understand what I was talking about. (I think that by then Tom Haller was getting a bit desperate about job security and was thus more willing to experiment), and though I had some very small influence on a move or two, eventually we parted ways. Casting about for a new connection, I wrote to Sandy, conversations ensued and he commissioned a sample annual report; the rest is history, as they say. I only found out later that Sandy had heard my daily five-minute radio pieces on KQED (the local NPR outlet) and had, in consequence, picked up a copy of my book (issued in 1982); though some web pages now describe that book as "sabermetric," it was actually a collection of disparate essays on baseball, about a third of which touched on numerical analysis (though some of those did go into topics not widely discussed by others till years after). Just how progressive were the ideas you combined to implement at the time? The ideas were, by conventional baseball standards, radical. The largest problem Sandy had, with using analysis and with a number of other things he wanted to do, was that he was an "outsider" by baseball standards, and had an entire baseball organization full of old-school baseball people, who were not amenable to new ideas, and most especially new ideas from an outsider. To this hour, I don't know how widely within the organization it was known who I was and what I did (something that changed, at least somewhat, when Billy took over). But we were already back then using most of the tools available today; arguably they were not as refined as what is now possible with the vastly larger database available to anyone at the click of a mouse (I spent seemingly endless hours hand-typing and manually double-checking minor-league stats every year), but they captured almost all of a really practical nature that is useful. Based on your dealings, what qualities does Sandy bring to a GM job? Sandy is, of course, extremely intelligent -- you don't coast through Harvard Law. He is also methodical and focused. Also very important, he has a definite "command personality"; he is not at all belligerent or authoritarian -- in fact, he is quite personable -- but there is never any least doubt who's in charge, and when he's angry about something, I wouldn't want to be the focus of that anger (which, fortunately, I never was myself). All in all, for any business he would be a first-rank manager. If that sounds like butter, it is not: He is really an impressive person. In this day and age, it is easy to forget what a pleasure it is to converse with someone who speaks in whole, grammatical sentences. If the Mets do indeed go with him, there will be, I reckon, some deep changes throughout the organization, and it will come out much the better for it at the end. It would be real fun to see him working with a decent budget in an era in which he would no longer have to be fighting superstition. How do you think his principles from Oakland will adapt to a New York and that type of budget? I think Sandy is a man who’s got a very practical streak in him. I think he can adapt to his environment. But he also expects his environment to adapt to him. Remember that he has a clear grasp of what the concept general manager means. He’s the guy who is responsible for it all. There’s that semi-famous quotation that showed in either in “Moneyball” or “The Numbers Game” to the effect that there was no other industry in which middle management determines the course of the organization. So he’s the guy in charge. And he knows it. And he makes sure that everybody else knows it. But he’s the classic example of the iron hand in the velvet glove. He’s a very easy man to work with by and large. He’s very personable and very affable. But if push is coming to shove at some point, there’s something that he doesn’t like, there’s no doubt who is in charge. This is not the same as some of the old-school guys who thunder and rant and rage. With Sandy, it’s much smoother than all of that. Another thing that’s made much of, and I think correctly, is his Marine Corps background. But I don’t think it’s so much that being in the Marine Corps shaped him as that the kind of shape he was -- if you want to put it that way -- sort of naturally gravitated to the Marine Corps. He seems very casual and very laid back, but he’s in point of fact very disciplined. New York, of course, is famous for being a very critical market. They want performance, and if they don’t get it they get very antsy very quickly. So it will be interesting to see. I suspect there will be a honeymoon period, and then we’ll have to see where it goes. I mean, he has a job on his hands there with that team. I think, frankly, that if the organization works with him, he’ll work well with the organization. If the organization as it is doesn’t work well with him, there will be, I suspect, changes. Not immediate. Not sweeping. He’s not the kind of guy who comes in with a new broom who throws everybody out. He’s going to try to work with what’s in place. But, in the end, people are going to comport with his view of things or they won’t be around is my opinion. The principles from Oakland can be applicable anywhere, right? Boston might be an example where it works in larger markets, too? This is true. There is a widespread error that what the A’s do is “Moneyball” and “Moneyball” is what the A’s do. They’re two different things. Analysis and “Moneyball” are two very different things. “Moneyball” is a concept that you might say developed under Billy Beane and was the concept of trying to get maximum value for your money in whatever the market undervalues. And when I was there with Sandy and then later with Billy, what the market undervalued was offensive performance, especially on-base percentage and walks. That’s the basis of analysis, and it remains the basis of analysis to this day. To this hour, the basic principle of analytic baseball is don’t make outs. And that hasn’t changed. There are many new metrics for analyzing players, but they are all fine-tuning of basic principles that go all the way back to before Bill James. They go all the way back to Earnshaw Cook and probably even farther back than that. “Moneyball” as the A’s practice it now seems to be focused on getting good defensive players -- speedy little guys, really almost a small-ball philosophy in some ways. It certainly isn’t the kind of analysis that we were doing when I was there because you can look and see that basically they have a lot of low on-base percentage guys. And it doesn’t look to me like they’ve been all that successful with it. Run prevention is the phrase you hear a great deal these days. And look how well it worked for the Mariners. I mean, the Mariners hired Tom Tango, who is probably the foremost analyst of modern times, and look where it got them. Granted, they had some tough luck in ways. But, still, there’s the good-old way in my opinion -- and I think that’s what Sandy still believes in, although I haven’t talked to him in a long time. As an example of the kind of guy Sandy is, I happen by chance to have been in his office when he was brought the information hot off the press that Mike Norris had been for the second time arrested for cocaine. A lot of guys in that position would have blown up. But, instead, he just sat there with this big grin just nodding like, “Oh, man. What a joke. Here we are again.” He has been involved with baseball with a team as recently as two years ago with San Diego. So if anyone had the perception that things had passed him by, that the theories of 20 years ago aren’t applicable, it still works? Absolutely. If you read a lot of what people write about analysis, or sabermetrics as they like to call it these days, you see an awful lot of all kinds of complex measures and all sorts of complex equation writing and so forth. But as I said somewhere a few months ago in an article I did for The Baseball Analyst, you mustn’t confuse precision with accuracy. And the fact that you can calculate things out to two or three decimal places doesn’t mean it’s particularly more accurate than what we did in the good-old days. In 1982 in my book, I had a formula that involved nothing but at-bats, walks, hits and total bases for predicting runs. And I just happened to look today. Its average accuracy applied to 2010 -- 30 years later -- is 3 percent. The most accurate formulas available, if you tweak everything and fine-tune everything down, you’re going to get down to 2.3, 2.35 percent. So the major principles are very clear, very straightforward. They still work. And I think that’s probably what Sandy is going to be looking at. Basically, he’s going to be getting guys who help produce runs. Or, if they’re pitchers and fielders, help reduce runs. You really don’t have to be very fancy with that. It’s not a question of being a dinosaur. I’m sure Sandy knows all the modern measures. It’s not going to be like he’s a stat-head who comes in and says, "This is all we’re going to do, by the numbers." But he’s going to let the numbers have an important voice, in my opinion. He was talking somewhere about the Earl Weaver school of thought and espousing the three-run homer versus the bunt and hit-and-run mentality. Can he really espouse the three-run homer at a ballpark with Citi Field’s spacious dimensions? Small-ball is the very antithesis of what analysis says is the right way to go. All the small-ball play -- the sacrifice bunts, the stolen base, the hit-and-run -- run completely contrary to what modern analysis says. But that works at a big ballpark? Remember, a lot of people think modern analysis sprang from on-base percentage and home runs. It doesn’t have to be home runs. What it has to be is above all else don’t make outs. This is why high on-base percentage is important. And another mistake people make when they hear talk about on-base percentage is they think everybody has to walk a lot. Certainly in the ’80s, during Sandy’s and especially Billy’s time, there was placed a lot of emphasis in the minor leagues on teaching people to walk. But that’s not the point. Walks are a byproduct, not the goal. The point is to understand the strike zone -- swing at pitches that are in the strike zone. No harm in that. Just don’t swing at pitches out of the strike zone. I follow the Giants rather closely. That’s as much as I’m involved with baseball these days. And Shawon Dunston made a famous remark: If you want to see walks, be a mailman. You just don’t know what to say about that. Another famous remark of his was walks are cheating the game. That’s the opposite. The analytic method is basically: Control the strike zone. Don’t make useless outs. Swing at pitches when you get them. If they don’t want to give you your pitches, take the walks. It doesn’t have to be power. It doesn’t have to be driving in runs with home runs. It’s just don’t waste outs. It’s just don’t have the first guy get on base in the ballgame and the second guy in the ballgame bunt him. That’s just wasting. It’s avoiding that kind of mindset that’s important. Go out there, score runs and don’t give up runs. It doesn’t have to be the three-run home run. It can be the two-run double. It seems like with the Mets there wasn’t a cohesive philosophy between the majors and all levels of the minors. How might Sandy Alderson impact that? I think you’ll see that change drastically. [The A’s] worked very much toward having a uniform philosophy top to bottom. This was even truer under Billy, but very much so under Sandy. You’ve to remember, again, when Sandy came in he was fighting an uphill battle. Everything and everybody in the organization said, "This guy is an outsider. Why should we be minding him?" And he had a lot of stubborn resistance. Even Billy did in his time. And Billy came in during the mid-’90s. … They worked very hard toward teaching guys in the minors what the philosophy was. And not only that, but why the philosophy was, so it didn’t seem like this is some goofy idea those guys have. Times have changed and I suspect a lot of young players coming in have some idea of what analysis is, although maybe I’m overestimating that. But there will definitely be a uniform philosophy from top to bottom about as quickly as that can practically be brought about. How would he balance offense versus defense? You don’t even have to get terribly detailed. You can see right away that offense and defense, meaning runs scored and runs allowed, have equal weight in winning ballgames. Everybody understands that. That being so, defense being partly pitching and partly fielding, it’s immediately obvious that fielding is worth less than offense. It’s a part of defense. If you figured that fielding is half of defense, which is wildly exaggerating it because pitching is such a big part of it, that still makes offense twice as important as fielding. That doesn’t mean fielding is unimportant. But, all things considered, when you have your choices, you prefer the guy with ash rather than the guy with leather. The extent to which Sandy still believes that, I would say probably still a fair bit, but it’s been so many years since I’ve talked to him. But I think you’re going to see an emphasis on offense and on quality pitching and fielding is one of those things, it’s like an extra. If you can get it, you get it.

|